The Tragedy of Raymond Cirrotta

So far, we have mostly explored case studies of musical obstruction (i.e., auditions block people from participating), but consider sonic spaces’ ability to enable. In group settings, people tend to make more irrational decisions since blame can be shared amongst the group. This phenomenon is well documented in the field of psychology and is often referred to as risky shift.[1] But what factors lead to groups making extreme decisions? More specifically, what aspects of social interaction or participation build an environment that allows risky shift to occur in the first place? Consider the concept of music as an enabler. Music as a form of propaganda can enable leaders to control the people listening to music.[2] Music as a form of protest can enable suppressed groups to energize and take action.[3] It is nice to sit back and relax when music is acting as a force for good, but what do we do once people start to abuse its power for the insidious?

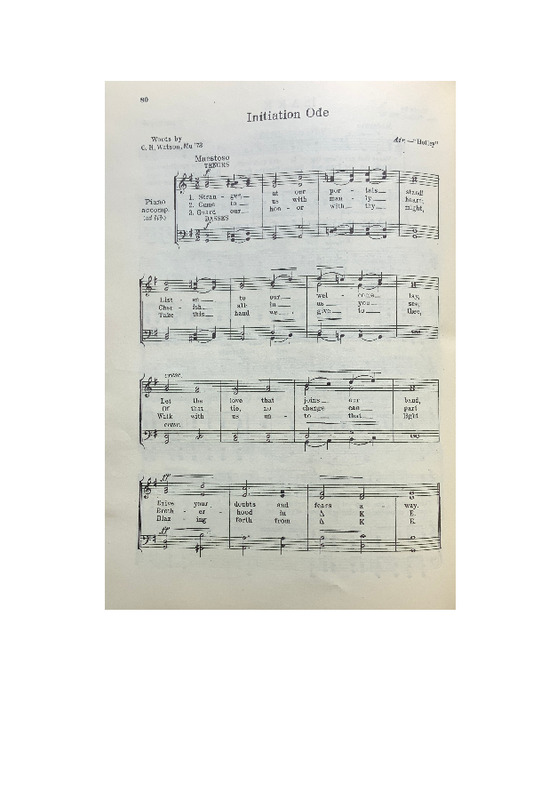

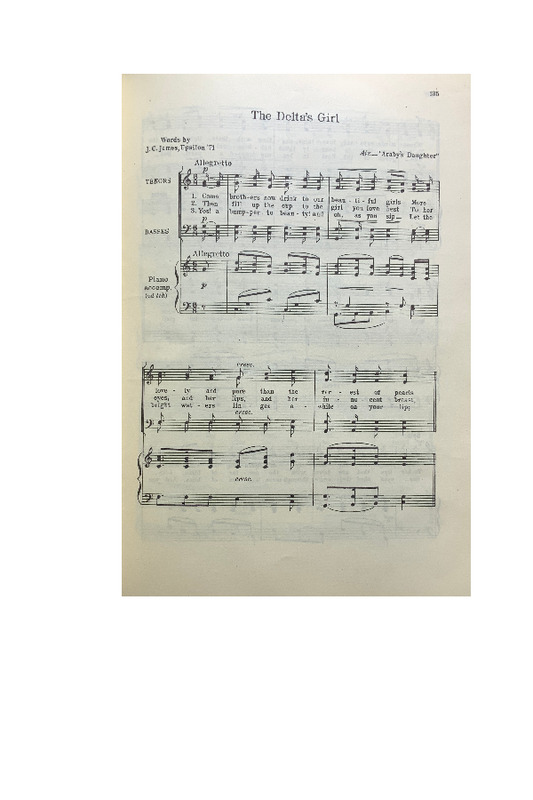

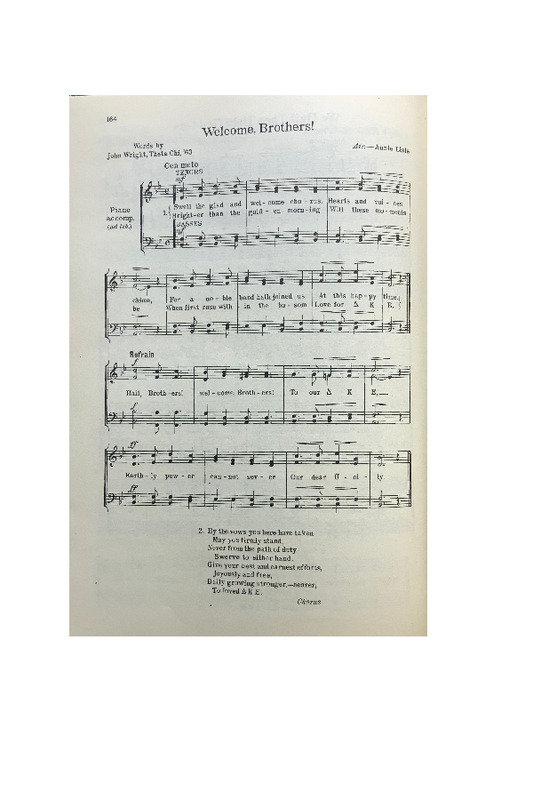

Delta Kappa Epsilon (ΔΚΕ) is a defunct fraternity that operated from 1853 until its dissolution sometime in the 1970s. Unlike other fraternities on campus, ΔΚΕ took time to carefully document its musical traditions, insofar as to have published copies of their songs in the form of sheet music that still exists today.

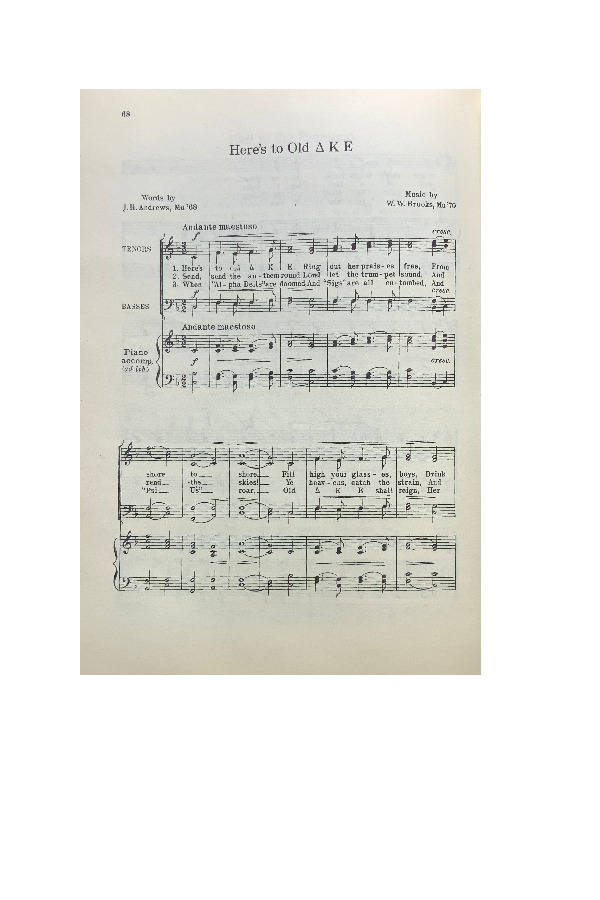

One ΔΚΕ song I ran into during my archival work is “Here’s to Old ΔΚΕ.” The lyrics of the song go,

“When ‘Alpha Delts’ are doomed, and ‘Sigs’ are all entombed, and ‘Psi U’s’ roar,

Old ΔΚΕ shall reign.

Her glory shall remain forevermore.

Forevermore…

Amen, Amen.”

The immediate takeaway of this song is evident: everything but Delta Kappa Epsilon is temporary. The repetition of “amen” at the end also engenders a pseudo-religiosity to this music that reinforces a sense of self-deification from the brothers in this fraternity. This messaging is even implicit in the musical structure of the song: the C-7 chord leads into a fulfilling F-major (tonic) with rich timbre from the F3. This cadence is not unique to “Here’s to Old ΔΚΕ,” however. Almost every single piece in the songbook ends on the tonic, giving a feeling of finality to the brotherhood and compounding seemingly masculine ideals. The issue with having such strong, uninhibited, and toxically masculine words bouncing around is that it can enable people to rationalize otherwise unjustifiable actions.

On March 18th, 1949, six ΔΚΕs and two Tri-Kaps walked into Raymond Cirrotta’s dorm. Two of them, Thomas Doxsee and William Felton, beat Cirrotta after waking him and ransacking his room. He was found on the ground by his roommate, taken to the local hospital, and died of cerebral hemorrhage on the morning of the 19th.[4]

The reasoning behind this murder? Cirrotta was seen wearing a varsity letter jacket.[5] Other sources have suggested that Cirrotta’s affiliation with the Progressive Party could have incensed the politically conservative aggressors. There is also the possibility that Cirrotta received the letter jacket from a football player he was seeing at the time, adding sexuality to the list of motivators (not that any motivator justifies what took place). The most shocking detail in the Cirrotta story is the punishment Doxsee and Felton received: suspension and a few hundred dollars in fines. The other men walked away without consequence.

Music that emphasizes masculine strength and, in some cases, personal or group deification, not only places but reinforces social power. In the case of ΔΚΕ, we see music enabling a group of men to empower themselves socially. However, this is not empowerment in the productive sense, but in a way that allows members of this space to abuse power without consequence. Once again, the “it is all in good fun and games” argument tends to come up as a defense. That may very well be the case, but once the ideology of music — say, ideology that enables the abuse of power — becomes implicitly accepted by the musical participants, other people tend to suffer as a result. The Cirrotta incident is a particularly extreme example, but think about other Dartmouth music that has implied a certain social dynamic. “Eleazar Wheelock” belittles American Indians and places the white, Anglo-Saxon man on a pedestal. Singing “Men of Dartmouth” implies that women should not be entitled to their position at this co-ed institution. Again and again, music at Dartmouth has carried implicit social messages that, even when performed in good faith, have hindered social advancement for marginalized groups while concurrently enabling the socially powerful to reinforce their status.

We have considered who gets to participate and where we participate as facets of musical participation and community music building at Dartmouth. We will now explore idiosyncrasies within Dartmouth’s vast musical landscape that provide different lenses from which we can evaluate these questions. These case studies will lead us to ponder a critical question: where is music at Dartmouth going?

[1] Teger, Allan I., and Dean G. Pruitt. 1967. “Components of Group Risk Taking.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 3 (2): 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(67)90022-4.

[2] Velasco-Pufleau, Luis. 2017. “‘We Are the World’: Music and Propaganda in Democracy.” Billet. Music, Sound and Conflict (blog). 2017. https://msc.hypotheses.org/11.

[3] Da Silva, Dana. 2013. “Music Can Change the World.” Africa Renewal. November 22, 2013. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2013/music-can-change-world.

[4] Syrett, Nicholas L. 2009. The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities. Chapel Hill, UNITED STATES: University of North Carolina Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/dartmouth-ebooks/detail.action?docID=454839.

[5] http://voices.washingtonpost.com/shortstack/2009/03/sixty_years_ago_this_week.html

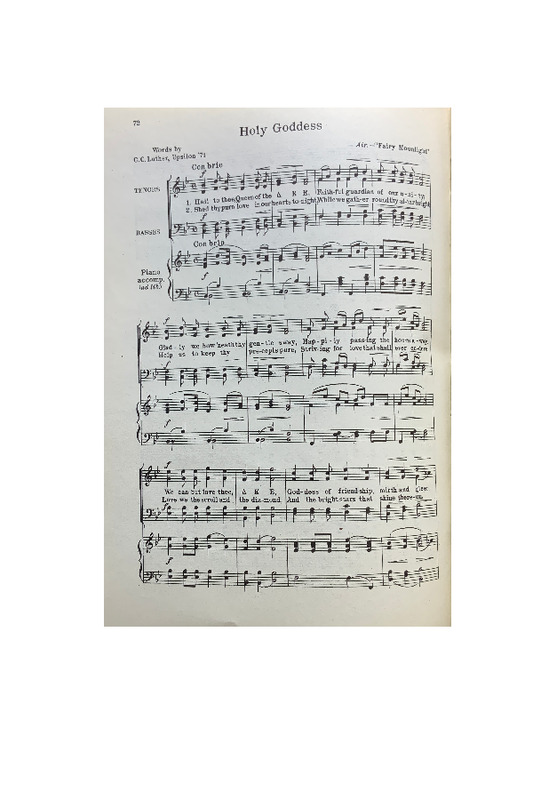

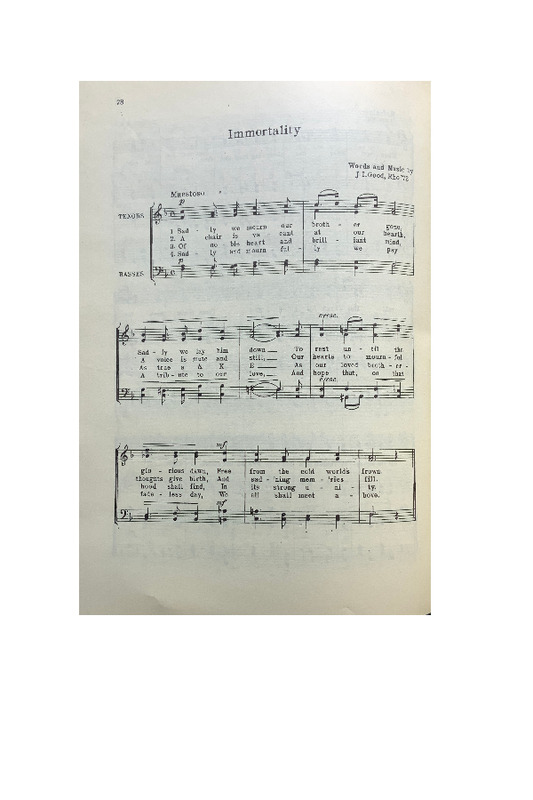

Additional ΔΚΕ songs from the ΔΚΕ songbook:

Previous: Rah-Rah-Rah... Right? -- Next: We're Just Kidding Around!