Rah-Rah-Rah... Right?

Other forms of music that often get overlooked are sports cheers, chants, and songs. Dartmouth has a long tradition of sports rivalries in the Ivy League, so it is not surprising to find out that there exist several songs about Dartmouth athletics. Many of these songs fall under the category of Dartmouth Traditionals and are still sung today. However, the versions of these songs we hear today are not the same as the ones sung decades ago. Are these changes enough? And how do they affect the sonic space that students, faculty, and alumni create?

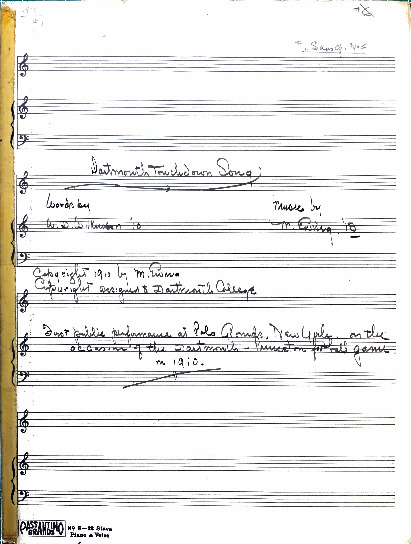

One of the most cherished Dartmouth Traditionals is the “Dartmouth Touchdown Song.” Written by W.D. Wilkinson ’10 and set to music by Moses Ewing ’13 in 1910, the piece, about 30 seconds in length, has become iconic in the Dartmouth community and is still sung at home games today. Consider the first part of the original version of the song:

“Come stand up men and shout for Dartmouth

Cheer when the team in green appears;

For naught avails the strength of Harvard

When they hear our mighty cheers:

Wah-who-wah-who-wah!”

Here is the revised version that is still sung today:

“Come stand up shmen and shout for Dartmouth

Cheer when the team in green appears;

For naught avails the strength of Harvard

When they hear our mighty cheers:

Rah rah rah!”

There are only two changes in the song. The first is that “men” is changed to “shmen,” a gender-neutral abbreviation for “freshmen.”[1] The second is that the words “wah-who-wah” — a phrase derived from Native American war chants — are replaced with “rah rah rah!” Although these cures seem to eliminate any problematicism in the song, a hard fact remains: it is still a song that takes derivations from a Native Indian war chant. To some, these minute alterations may be everything the school needs to do to clear the air. But to others, say, Native American students, the changes are just a veneer of political correctness that give those participating in the music a clear conscience. This is especially true in the setting of athletic venues where Native American representation on the fields, courts, or otherwise is already lacking.

It is also worth asking whether or not the changes do enough for women at the school. Perhaps the change from “men” to “shmen” checks off all the boxes for the “Dartmouth Touchdown Song,” but how meaningful is that if athletic music fails to respect this group in other ways? For example, the Dartmouth Aires still sing a football traditional called “Son of a Gun” which has the lines,

“And if I had a daughter, sir

I’d dress her up in green.

I’d put her on the campus

Just to coach the freshman team.”

The implication of this song is that a Dartmouth alumnus (implicitly a male) would “dress” his daughter up to physically attract men on the football team. Not only does this sexually objectify women at Dartmouth, but it also does little to dissuade implications of sexual assault on campus. In an interview with The Dartmouth, David Peterson ’10, musical director of the Aires, said that “the group has long struggled with deciding whether or not to sing it at shows,” and that the inherent conflict lies in “[doing] what the [alumni] want or… [trying] to go along with the obvious changes that are going on at the school.”[2] But why should this be a conflict at all? Put differently, the decision comes down to this: 1) continue singing a song at the cost of the humanity, individuality, and safety of women at Dartmouth or 2) nix the song from the common repertoire to the chagrin of a handful of alumni. Traditions can bring communities together, but we must be vigilant about watching for when they start to stand in the way of progress.

Compositions such as the “Dartmouth Touchdown Song” or “Son of a Gun” can be thought of as more formal music. That is to say, they are part of a large canon of music that is regularly performed by a majority of the college constituency. But what about something less formal, say, a team-specific cheer? These may only be performed by members of a specific team and completely unknown to anyone else in the community. An excellent example of such a cheer comes from the varsity men’s swim and dive team. At the start of every meet, they stand in a tight circle and scream the following while jumping up and down:

“Kipsalana, Kapsalana Squish Squa

Tie Hi Silicom Sku Cum Wa

Mojo Mummik

Muka Muka Zip

Dartmouth Dartmouth Rip Rip Rip

Tie Hi Sis Boom Ba

Dartmouth Dartmouth Wah Who Wah!”[3]

I have been told of two potential geneses for this cheer. The first is that it comes from a war cry native to the indigenous people of the Upper Valley. The second is that it is a riff (read: a mockery) of Native American “sounds” that were strung together to be intimidating. Either way, the origins of this team cheer appropriate Native Indian culture at best, mock it at worst. The swim team’s post-meet cheer is not much better either, saying:

“Boomba Boomba

Rah Rah Rah

Dartmouth Dartmouth

Wah Who Wah!”

I have spoken to several members of the swim team about this chant, and almost everyone has acknowledged the problematic nature of these chants and their intricate ties to the Native American community. This raises the question: why do they continue to participate in such music? Eduardo Herrera has written extensively on the relationship between sports chants and the deindividualization of participants.[4] In his paper, he argues that sports chants (specifically, soccer chants in Argentina) reinforce values of masculinity and endurance, values that are at the core of men’s sports. Critically, he postulates that the loss of individuality during these performances enables whole communities to temporarily sidestep moral objections and participate in “expressions, slurs, and profanity that most people might refrain from using otherwise.” I argue that a similar phenomenon occurs during Dartmouth sports cheers. Despite the fact that members of the swim team have confessed unease in the cheer, to my knowledge, not one person has ever objected to its use during the season where it is performed almost every other week.

In 2018, the men’s swim and dive team changed the cheer to reflect the political climate in which it found itself. Today, the cheer is as follows (the bold text highlights the changes made):

“Kipsalana, Kapsalana Squish Squa

Tie Hi Silicom Sku Cum Wa

Mojo Mummik

Muka Muka Zip

Dartmouth Dartmouth Rip Rip Rip

Tie Hi Sis Boom Ba

Dartmouth Dartmouth Rah Rah Rah!”

Similar to the example of the “Dartmouth Touchdown Song,” the change from “Wah Who Wah” to “Rah Rah Rah” is like using a band-aid to fix a leaking pipe. While it ostensibly does the job, it does not address the core issue itself; some, including myself, would argue that it actually does not even address the superficial problem either.

When examining music in vast physical settings such as athletics, we find that a desire to preserve tradition and the loss of performers’ individuality allows certain musical injustices to persist. This conclusion is unique because it marks the first time we find that musical exclusion — though still prevalent — is the lesser issue. Rather, athletic music and upholding tradition enable the already powerful to reinforce their status as the socially dominant (i.e., the swim team appropriates Native American culture, etc.). Thus, unique to sonic spaces is their ability to enable.

[1] https://www.waywordradio.org/shmen/

[2] Krishna, Priya. 2009. “Cohog Hums.” The Dartmouth. October 8, 2009. https://www.thedartmouth.com/article/2009/10/cohog-hums.

[3] Taken from the official chant given to me during my tenure on the Swim & Dive team

[4] Herrera, Eduardo. 2018. “Masculinity, Violence, and Deindividuation in Argentine Soccer Chants: The Sonic Potentials of Participatory Sounding-in-Synchrony.” Ethnomusicology 62 (3): 470–99. https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.62.3.0470.

Previous: Phil Hanlon Take a Shot! -- Next: The Tragedy of Raymond Cirrotta