Dartmouth's Campus Climate from the 1950's-1960's

The Great Issues of the Nation

The 1950s and 1960s were a tumultuous two decades both at home in the U.S. and abroad. This era was marked by the intense geo-political rivalry of the Cold War, as the United States and the Soviet Union were infamously engaged in a nuclear arms race. The United States became increasingly involved in the Vietnam War (1955-1975), a conflict that became a focal point for anti-war protests and activism. In the United States, the Civil Rights Movement had gained momentum. Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Little Rock Nine (1957), the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956), and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 challenged the codification of racial segregation and discrimination across the nation. The 1960s also saw the emergence of the women's liberation movement, with students actively involved in challenging traditional gender roles and advocating for equal rights. The '50s and '60s were decades defined by a complex interplay of political, social, and cultural dynamics that would come to a boil in the latter half of the 20th century.

Adhering to the counterculture movement of the 1960s, many students were at the forefront of movements seeking societal change. Organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were crucial in rallying peers. Formed in 1960, SNCC played an important hand in organizing grassroots initiatives and coordinating student-led protests. As the United States escalated its involvement in the Vietnam War, students on college campuses became increasingly vocal in their opposition. Students held campus protests and demonstrations, with many participating in the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (1969).

Student activism during the '50s and '60s played a crucial role in various social and political movements, particularly in the context of civil rights and anti-war efforts. Dartmouth College was no different.

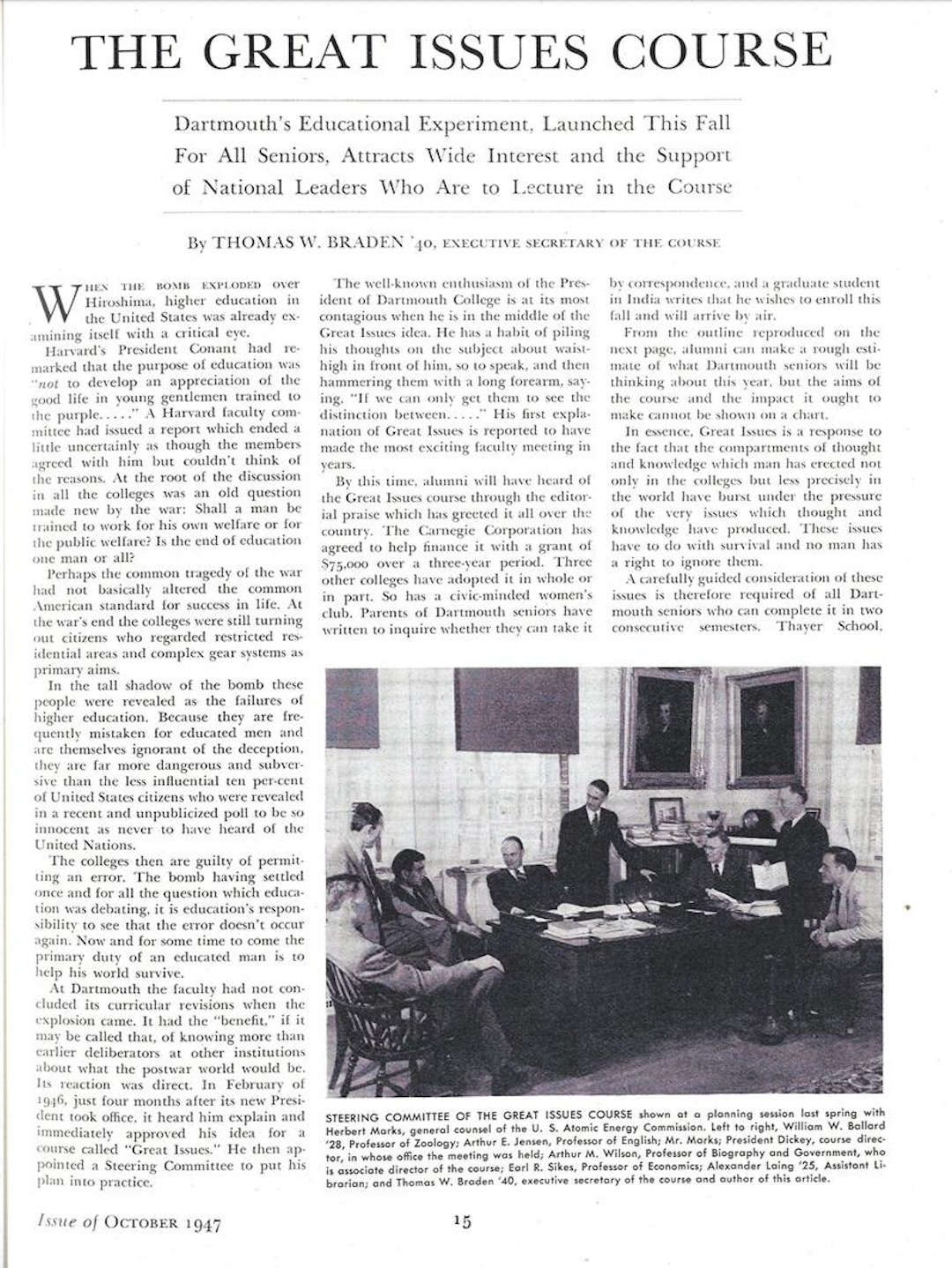

"At the root of the discussion in all the colleges was an old question made new by the war: Shall a man be trained to work for his own welfare or for the public welfare? Is the end of education one man or all?

The colleges then are guilty of permitting an error. The bomb [Hiroshima and Nagasaki] having settled once and for all the question which education was debating, it is education's responsibility to see that the error doesn't occur again. Now and for some time to come the primary duty of an educated man is to help his world survive."

- Dartmouth's Alumni Magazine, 1947 Issue

"Well, they used to have this course called Great Issues. And I used to sit out and listen to it even though I wasn't in that class. And they did have Roy Wilkins speak. And George Wallace came to speak. And the fellow on the African American side, he almost had a riot. But I felt he had a right to speak even though his views might be different from mine."

- Dr. John Buckner '62

“Our agreed-upon objective was to create enough disruption and chaos during the speech to compel the national news media (which we knew would be at the speech) to report on our protest nationwide, so that Black people nationwide would know that we, too, were committed to the then fierce struggle being waged across America against the racism and fascism that George Wallace advocated.”

- Robert Bennett '69