The Social Experience of Black Students at Dartmouth

Social Life

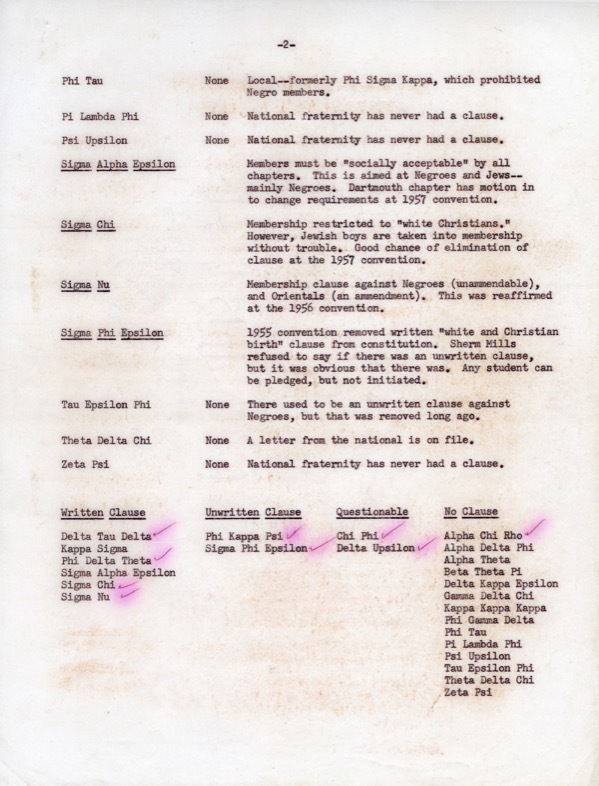

As the administration began to admit a more diverse student body to the College, student groups on campus were tasked with a microcosmic decision: would fraternities admit Black students into their brotherhood?

In her own digital exhibit, Sabrina Eager '23 touches upon the history of fraternity discrimination on campus. Eager '23 notes that Dartmouth's administration became aware of the discriminatory clauses in fraternities’ recruitment processes in the 1940s. When President Dickey was inaugurated in 1945, a major point of contention was reopening fraternities after WWII. Allegedly, as Eager quotes, “a major point of debate was the discriminatory clauses in the constitutions of some chapters, as members of the Board of Trustees were concerned the clauses would have a negative impact on public image" (Eager 2023). President Dickey dispelled any debate in a 1948 pamphlet, circulated specifically to potential brothers: “This college neither teaches nor practices religious or racial prejudices, and I do not believe it can for long permit certain national fraternities through their chapter provisions or national policies to impose prejudice on Dartmouth men" (Dickey 1948).

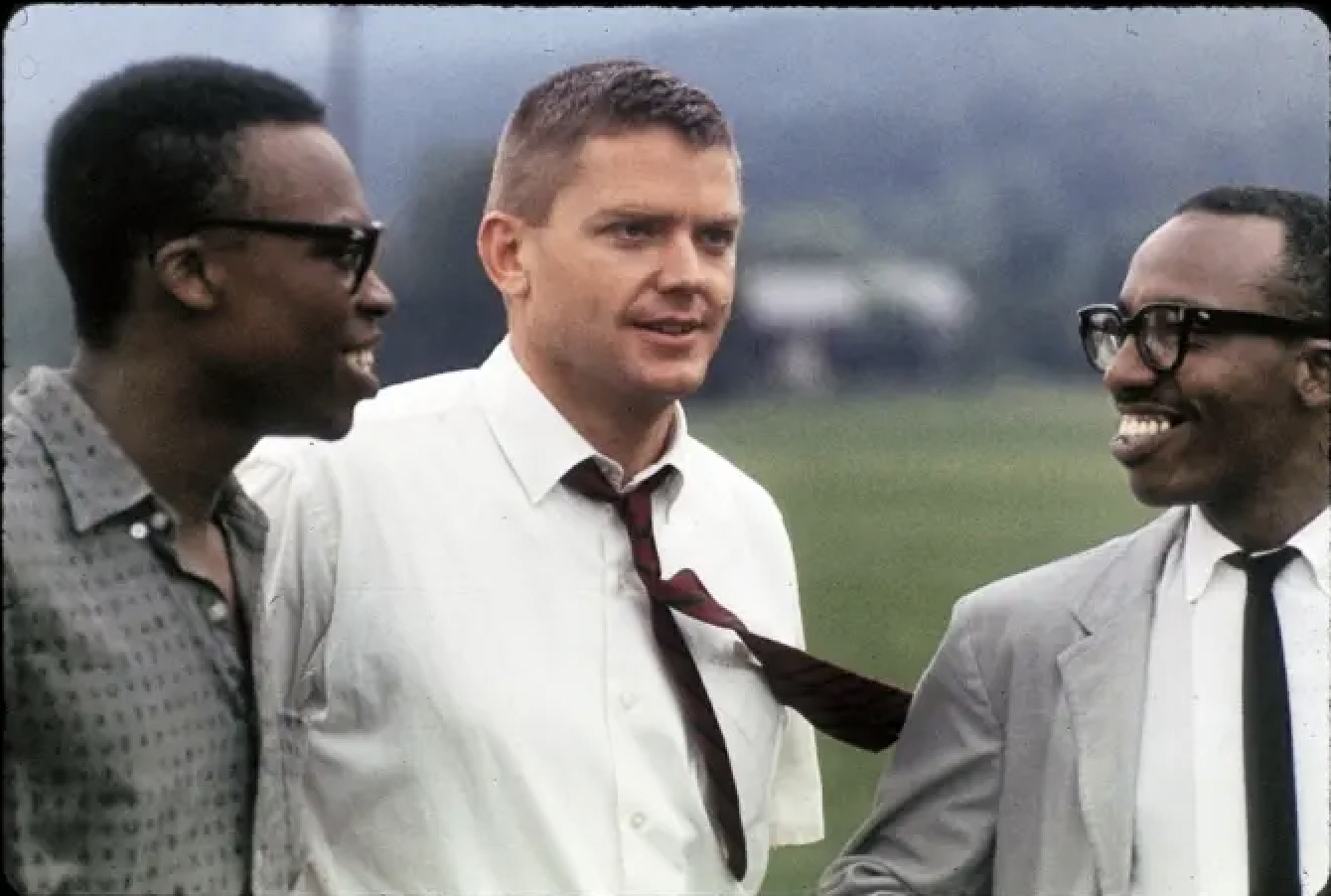

As can be seen in the scanned reports to the right, attempts to desegregate from the top down were not unilaterally successful. Black students were forced to find other avenues for socialization, such as religious or political activist groups. Dr. Buckner found a social network in forming his own fraternity with his friends, Doug Skopp [‘63], Bruce MacPhail [‘66], and DeWitt Bell [‘62].

We decided to form our own fraternity. And we called it the Sigma Society.

- Dr. John Buckner '62

We did have one mixer. But I didn't really know how to dance [laughter], so I probably faked it a little bit. I forgot which college it was. It may have been Radcliffe.

- Dr. John Buckner '62

Social Involvement

For those with both the free time and the moral impetus, getting involved with student groups was another popular social outlet. With the nation's issues pervading campus, there was no shortage of orginizations to join when seeking a more issue-oriented fraternity.

Well, at Dartmouth, there was the African American Society, in which we had some discussions. They wanted to have a visiting professor and we talked about it. We demanded a Black studies curriculum so we could get a Black studies professor at that time.

- Dr. John Buckner '62

“Black demand, white awareness, [and] riots in the cities” as well as “a fundamental contradiction between an asserted opposition to racism” and the low numbers of black students on campus, pushed Ivy League institutions into action"

- McGeorge Bundy (a Yale alumnus), President JFK’s (Harvard alumnus) and LBJ’s National Security Advisor

I used to do the interviews for the students that were being applied for acceptance at Dartmouth... [in] the ABC or A Better Chance program, which gave students from African American communities extra skills in Math and English. A fella named Jim Simmons led that.

- Dr. John Buckner '62

[At] the Dartmouth Christian Union... we used to do things like shop firewood for farmers or collect clothing for people who needed it.

- Dr. John Buckner '62