Dissent

Opposition to the Vietnam war began right from the conflict's outset. Protest against the war was carried out predominantly on college campuses by left-wing student groups who opposed the way that the U.S. military was conducting the war. Though the vast majority of Americans still supported the war in its early years, the small liberal minority that opposed it made its voice heard as many prominent artists, intellectuals, and a small but outspoken minority made its voice heard. As the war dragged on, support for the anti-war movement grew rapidly as the American people began to turn against the war. Demonstrations against the war became more intense and widespread, sometimes even resulting in violence. By 1969, 48,736 men had died, including three Dartmouth men. A September Gallup Poll found that 58% of interviewees believed that sending troops to Vietnam was "a mistake."

The lack of faith was reflected by the ROTC numbers, which had plummeted in 1967 to only 250 cadets participating out of a total of 3,100 undergraduates, down from the pre-Vietnam numbers which consistently were around 800 participants.

Individual Dissent

Many, including Mr. Larner, were forced to reassess their personal convictions. Larner grew up in a military family and had spent much of his childhood fantasizing about what his time in the military was going to be like.

However, he like many Americans began to turn against the war. After, a weekend talking with one of his close friends, Larner decided that he would take a personal stance against the war. During training, Larner wrote a letter to his Company Commander, stating that

Larner was fortunate to avoid facing discipline, as he "was fully expecting to get arrested or put in jail." What is interesting about this quote is that it illustrates the juxtaposition that many Americans felt during this era. Even though Larner believed that the U.S. Government was conducting an "immoral war" he was adamant about completing his service for his country.

Dartmouth '64 Charles L. Marsh shared a similar sentiment to Edward Larner. Though he never expressed his views to any of his commanding officers, he stated years later in an essay "though I came to disagree with the war, I made a commitment to the Navy in the spring of 1960 and was comfortable honoring my obligations."

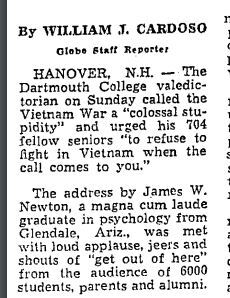

The Infamous 1968 Commencement

Dartmouth's 1968 College Commencement made nationwide headlines when '68 Jamie Newton, who was the class's valedictorian and a Quaker pacifist, gave a speech denouncing the war.

Newton's speech incited boos from the audience. However, most of his classmates gave him a standing ovation, illustrating the massive divide that the war created even across family lines.

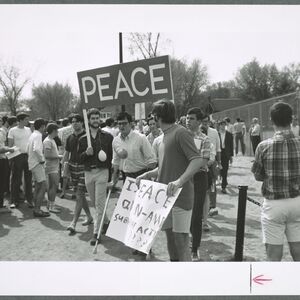

Campus Protests

Though still a fairly conservative college by national standards, many aspects of the counterculture movement made their way onto Dartmouth's campus. Throughout the 60's, channels for student activism continued to grow. Though Vietnam would later dominate student activism, the origins of these student groups were based around civil rights. SDS, or Students for a Democratic Society, was a left wing student group that organized civil rights and anti-war protests. Overall, student movements called for greater influence over the College's decision making. Despite originating in peaceful, constructive purposes, Dean Seymour claimed that

However, the vast majority of the protests were very tame and never in danger of becoming violent. It was commonplace to see peaceful demonstrations such as the anti-lines.

Bill Sjorgren described the "lines" in an interview he conducted with Rauner.

But even Sjorgren admits that "the Dartmouth protest there was nothing compared to what was going on in the cities."

The Parkhurst Occupation

The protests on Dartmouth's campus peaked on the afternoon of May 6, 1969, when about five-dozen students and alumni occupied Parkhurst Hall, the College's main administration building, to oppose the College's ROTC programs. The students then forcibly removed President John Sloan Dickey, Dean Seymour, and others from the building before nailing the front doors shut. They then issued a set of demands calling for ROTC to be abolished at the beginning of the next school year, for the college to provide financial aid to those receiving aid from ROTC, and for military recruiting to be terminated. Dartmouth ’71 David H. Green expressed years later why he took part in the Parkhurst Occupation:

The students took issue with the college providing resources for their classmates to fight in a war that they didn't believe in. The campus was largely sympathetic to the Parkhurst protestors. A student referendum on the issue that was answered by 88% of the eligible student body found that; "8.6% of the students wished to retain ROTC on campus, 29.8% wanted to phase the program out over the next three years, while 35% supported the elimination of ROTC as soon as student currently under contract graduated and 24.6% were in favor of immediate termination." The Dartmouth College faculty also overwhelmingly supported the elimination of ROTC as 76% in January of that year had voted to phase out ROTC over a three-year period.

Eventually, a judge ordered them to leave Parkhurst. When they refused, police officers stormed the building and found the protesters on a staircase, arms linked, chanting “U.S. out of Vietnam! ROTC out of Dartmouth!” The police arrested 54 protesters, most of whom were tried in Grafton Superior Court convicted of contempt of court and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Shortly after the Parkhurst occupation the College Trustees abolished ROTC, effective in June 1973. The overwhelming support from the student body, faculty, and national trends against ROTC programs made this decision seem straightforward. However, most alumni were not happy with this decision, as Associate Professor of Physics Arthur Leuhrmann found that 61% of alumni believed that it was wrong to have terminated the ROTC program.

Years later, under immense alumni pressure the trustees voted to reinstate ROTC in 1975 as part of neighboring Norwich University's ROTC program. ROTC instruction eventually returned to campus in 1985 as an extension of the off-campus program at Norwich University.

The 1970 Student Strike

On April 30, President Nixon announced an “incursion” into Cambodia, purportedly to clean out sanctuaries used by the enemy. Protests erupted all over the country. The scale of these demonstrations were profound, and some became violent. The most infamous incident occurred when National Guardsmen killed four students and wounded nine others at Kent State University on Monday, May 4, 1970.

Up to that point, the protests at Dartmouth had been relatively peaceful and constructive compared to those taking place at other schools. Then President John Kemeny--out of fear that the protests could turn violent as it had on other campuses--delivered a 30 minute address on a local radio station before canceling classes for the following week to allow for "the community to participate in intensive discussions as to how this community can best join hands in a united manner." Across the country, student strikes closed more than 450 universities.

The next day more than 2,500 people rallied on the Green. Class president Bill Koenig '70 urged students to treat the rest of the week seriously, calling it an opportunity for a student strike “not against Dartmouth, but by Dartmouth to provide a framework in which to act…to show our outrage at the war and repression at home.”

Conclusion

The 60's had been a time of dramatic change for the Dartmouth community. Like the rest of the country, it would take several years for the deep divides and scars to heal. Vietnam ultimately broke down the College's social order, as Dartmouth students created a platform where none had previously existed to voice their opposition to the College's "establishment."

As Dartmouth President John Kemeny recalled years after the war, "we witnessed a pulling together of the Dartmouth community, in which I take pride and which was most beneficial to the institution.” I hope that this exhibit has illustrated the numerous ways that the Vietnam Generation altered Dartmouth's campus. Though the war and the political climate provided the catalyst, it was ultimately the students on both sides who were brave enough to stand up for their beliefs that brought these changes into effect.