The Women Who Answered the Call to Serve

While all young men ages 18 to 26 were subject to the draft from 1964-1973, the Vietnam War's escalation required large-scale coordinated recruitment of volunteers to the female-dominated parts of the military, particularly to the Army Nurse Corps (ANC). This section of the exhibit will trace the ANC's history and recruitment efforts, illustrating where the ANC's public self-representation aligns with and diverges from these women's reasons for joining. Analysis of these materials reveals the attributes, both explicit personality traits and implicit social identifiers, of the Army's vision of the ideal nurse, reflecting the history of women in the U.S. military as a whole. Faced with a shrinking Nurse Corps and domestic trends that contributed to an overall national shortage, recruiters devised strategies that reified traditional notions of gender and sexuality while simultaneously appealing to growing numbers of single, career-oriented young women.

ANC membership peaked at about 57,000 during the World War II-era but fell to only 2,961 by 1963. In her 2006 article, "Officer. Nurse. Woman. Army Nurse Corps Recruitment for the Vietnam War,” Kara Dixon Vuic notes a public ANC statement from 1963 stating:

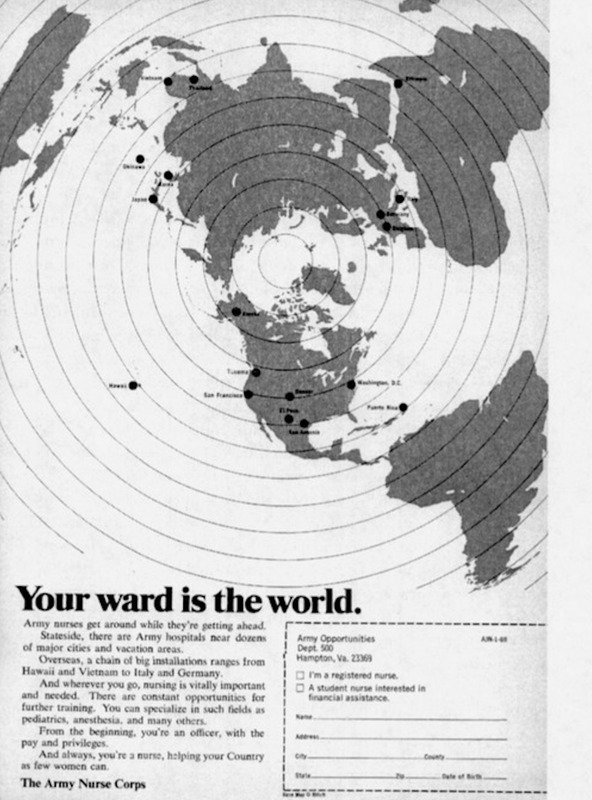

The rapidly intensifying conflict in Vietnam only exacerbated the need for nurses to take care of gravely wounded soldiers. However, unlike in prior wars, ANC recruiters had to compete with growing domestic demand for nurses spurred by longer life expectancies, hospital systems' expansion, and a greater proportion of the population seeking medical care through insurance programs. Furthermore, while nursing remained a female-dominated profession (99% of nurses were female), jobs that had historically only been open to men attracted many young educated women away from traditional women's fields. Understanding these hurdles, the United States Army Recruiting Command took on ANC recruiting responsibilities, which had previously been run d by the ANC through the Surgeon Generals' office. At their peak, over a hundred recruiters and counselors worked full time to bring in ANC volunteers through schools, private hospitals, and national nursing organizations. Operation Nightingale, launched in 1963, included the Army Student Nurse Program to incentivize volunteers, which paid students' nursing school tuition expenses plus a monthly stipend in exchange for active duty service. ANC nurses comprised roughly half of the ten thousand women who served in active duty in Vietnam between 1956 and 1973, with thousands more serving on bases outside of the active war zone.

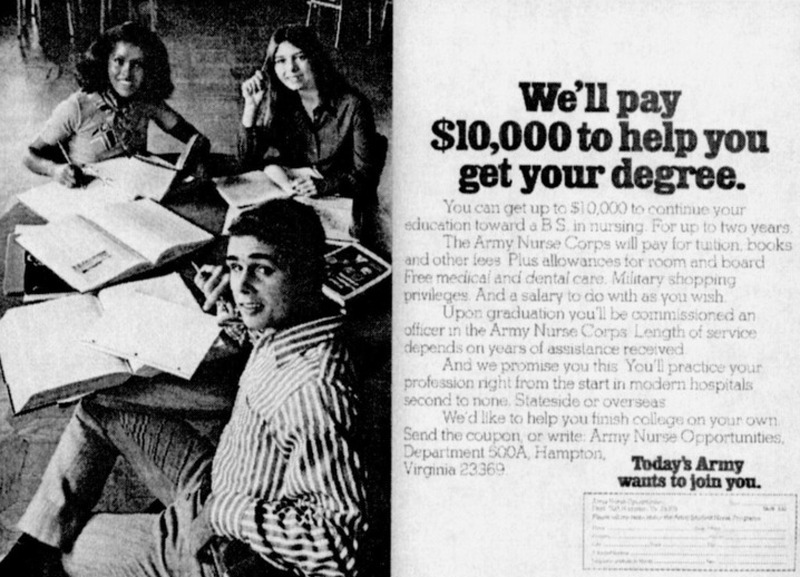

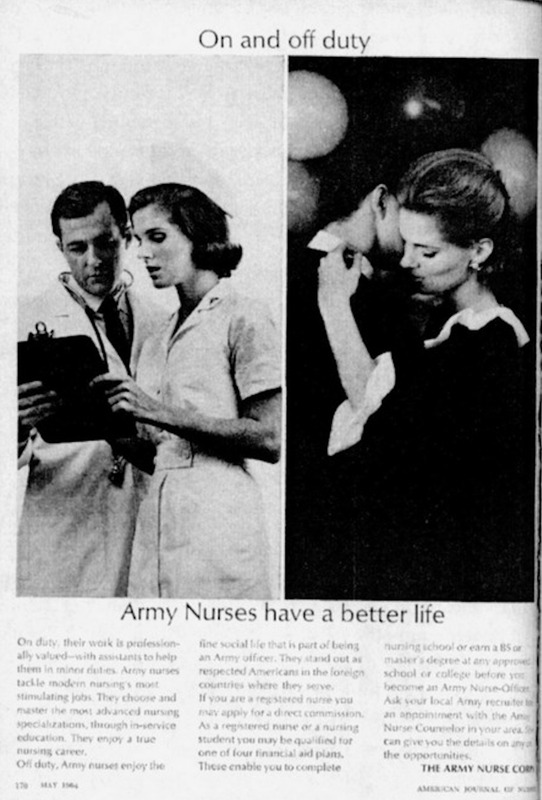

For the aforementioned 2006 article, Kara Dixon Vuic compiled a set of advertisements from the Army Nurse Corps History Office archives in Church Falls, Virginia. While the slogans point toward the nurses' abstract values and aspirations, the images reflect the army's implicit coding of the type of woman who most embodies these values. These advertisements reveal larger institutional imperatives, while individual testimony shows the extent to which individual women subscribed to these ideologies.

Appeal to single, career-oriented young women

Army recruitment materials resonated with women in their appeals towards women's professional ambition and desire for adventure beyond their life in their hometown. Several advertisements explicitly nod to the unique career opportunities provided by the Army Nurse Corps.

These narratives resonated deeply with Kathy Reynolds, who had a calling for nursing borne out of her experience of her father's sudden death due to a heart attack when she was a teenager. Ms. Reynolds decided she "could not take [her] final vows," after nearly seven years as a Sister of St. Joseph because her "next occupation was going to be the Spanish teacher." The Army Student Nurse Program helped ease the financial strain of nursing school at D'youville College in Buffalo, New York, where there was an army recruiting program,

After her service military, Reynolds continued a lifelong career in cardiac nursing.

Furthermore, advertisements appealed to women looking for a new, adventurous experience outside their hometown.

Both Anna Gerac and Florence Janisch felt compelled to travel and move away from where they grew up. Ms. Gerac said,

Similarly, to Ms. Janisch, the army was,

Attempt to enforce traditional notions of gender and sexuality

The expanding role of women in the military paralleled increasing attempts to police individual sexuality, and thereby to enforce traditional gender roles. President Harry Truman permanently integrated women into the United States Military at the end of World War II in 1948; shortly after, in 1949, the Department of Defense issued a decree, "Prompt separation of homosexuals from the military is mandatory." Up until this point, women were only called upon in times of war. In her book, The straight state: sexuality and citizenship in twentieth-century America, Margot Canaday points to an essential shift in that for women during WWII, service was merely a "brief interlude" before marriage, whereas women were now entering the force as a career opportunity instead of marriage. In Beyond Combat: Women and Gender in the Vietnam era, Heather Marie Stur notes, "tensions regarding women's place in the military, as well as assumptions about the sexual licentiousness of female nurses, carried into the Vietnam era." Parts of the military establishment resented the loss of the unique privileges that came along with male martial citizenship. In response to these anxieties, the military instituted formal regulations around which women were eligible to volunteer and put forth an image of the straight, chaste, feminine caregiver.

Kara Dixon Vuic describes the normative ideal of an army nurse as exemplified by Lieutentant Rose McNulty, who was featured in an ANC recruitment brochure with the description,

In addition to these more subtle tactics, women were asked directly about their sexuality before joining. The questions probed for sexual history, not necessarily sexual orientation itself. Brenda Vosbein recalls enlistment papers that questioned, “Have you ever had sex with someone of the same sex?” None of the women featured in this exhibit testify that fears of negative consequences due to their sexuality stood out as a consideration in their decision to serve. Many of them were only in their early twenties, lived at home, and had never been in a social context that allowed for the possibility of sexual relationships between women. They answered the question from the enlistment papers honestly and in the negative. Ruth Hughes recalls that while she “became aware of [her] emerging sexuality during puberty,” she never acted on those feelings, having internalized the idea that being “homosexual was criminal, dirty, and the worst thing you could be.”

Similarly, Anna Gerac had been told that one was “not of right mind to be a homosexual,” had only ever had relationships with men. Judith Crosby said to herself, ‘“That’s not me. I don’t have to worry about that one.’ I’m too busy partying and having a good time and having sex with men.” Darlene Greenawalt even replied, “Well, what’s a lesbian?” She “didn’t know what the term meant.”

In addition to the concern about lesbians in the military, service was considered fundamentally incompatible with motherhood. Women with dependents under eighteen were not permitted to volunteer. This presented an interesting contradiction because while the average woman in 1970 had her first child at 21 years old, the average army nurse recruit was 23 years old. Brenda Vosbein notes,

The following pages of this exhibit will explore the lived experience of gay women during their military service, following their successful recruitment.