The Narrative Style of W.D. Ehrhart

William Daniel Ehrhart of Roaring Spring, Pennsylvania was fresh out of high school when he enlisted in the Marine Corps in June of 1966. Despite being a gifted student whose enrollment in college would have exempted him from service, Ehrhart wanted to join the fight which he perceived as noble, drawing on the experiences of the Greatest Generation, who served in World War II. Ehrhart served three years in the Marine Corps, 13 months of which he spent in Vietnam.

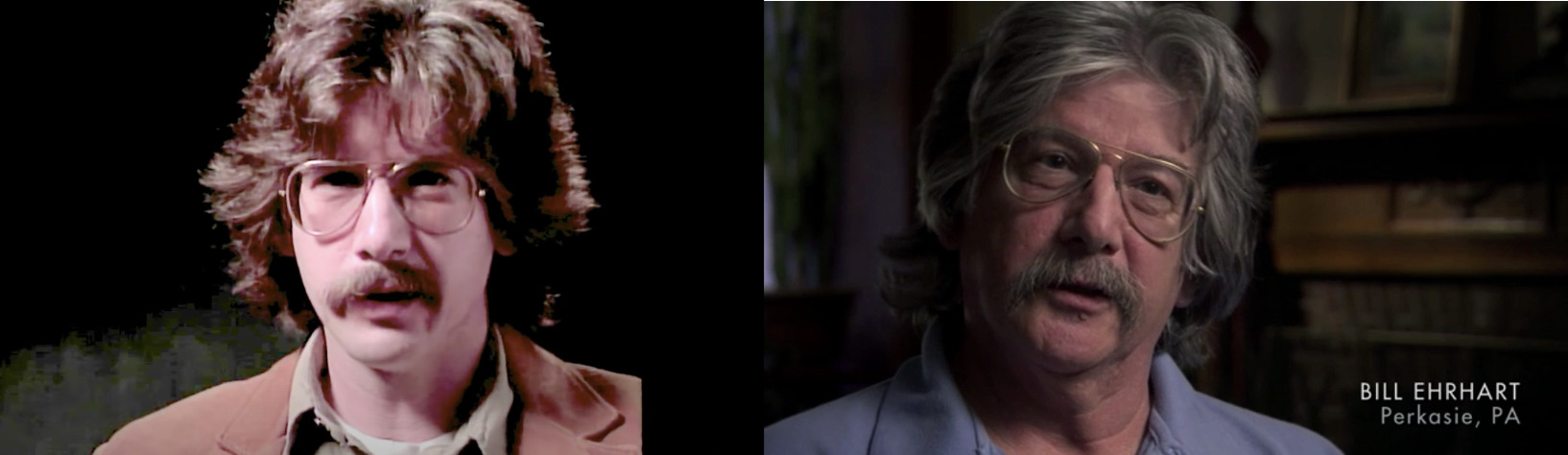

After returning home, Ehrhart occupied himself with a number of different jobs, but he is most known for his work as a poet and writer. He has written numerous books spanning from poetry about his time in Vietnam to nonfiction prose. Just as with Mr. Heaney, the following interview segments from the filmmaker David Hoffman and the Burns and Novick series The Vietnam War demonstrate his descriptive mind and keen ability for storytelling that made him an unsurprising selection for the documentary series.

In contrast to the previous page about Mr. Heaney, the interviews and narrative styles analyzed on this page were all done on camera. However, as the interview with David Hoffman was done as an oral history and thus not for such a large audience as the PBS documentary, there are worthy distinctions to be drawn. For instance, the tone of the Hoffman interview is distinctly more casual, which is made clear by Ehrhart’s lit cigarette flowing throughout the segment. At one point, he even expresses concern for “wasting [Hoffman’s] film,” which conveys the idea that either Ehrhart thought his personal reflections were unimportant, or that his self-deprecation was endearing.

Mr. Ehrhart’s narrative style is marked by his close relationship to the English language as a poet and writer. Throughout the Hoffman interview, Ehrhart employs similar rhetorical strategies as Heaney, particularly the first-person access to his recollections about his thoughts at the time. Additionally, he builds on his use of the first-person by switching back and forth between the first and second person to convey his own thoughts, while also drawing the viewers in, allowing them to place themselves in his shoes. For instance, in the Hoffman interview, Ehrhart recalls his distaste for the situation of identifying the enemy in Vietnam:

EHRHART: I saw four armed enemy soldiers the first eight months I was in Vietnam. And yet our battalion, during that same period of time, sustained seventy-five mining and sniping incidents per month, over half of them resulting in casualties. This is for a unit of about a thousand men. But there was no one to fight back at. And you begin to think, “These people are the enemy, they’re all the enemy.”

His combination of both the first and second person in this excerpt demonstrates his storytelling abilities and the effective manner in which he both conveys his own experiences and suggests to the viewer that they would think the same thing if they had been there with him. Additionally, in the Hoffman interview, Ehrhart leans on his proclivity for writing and metaphors to convey his feelings at the time:

EHRHART: Then for the reason that is that, you know, the kinds of questions that began to present themselves were just, the questions themselves were ugly and I didn’t want to know the answers. It’s like, it’s like banging on a door, you knock on a door, and the door opens slightly, and behind that door it’s dark and there’s loud noises coming like there’s wild animals in there or something. And you peer into the darkness and you can’t see what’s there, but you can hear all this ugly stuff. You want to step into that room? No way, you just sort of back out quietly, pull the door shut behind you, and walk away from it. And that’s what was going on. The questions themselves were too ugly to even ask, let alone if I had to deal with the answers.

His metaphor of this dark, frightening door to the unknown is Ehrhart using his subjective imagination to illuminate the uncomfortable and perhaps uncertain feelings he had toward the war in which he served. His use of metaphor as a feature of his narrative style is not only in line with his profession as a writer, but effective in communicating the uncertainty and ambivalence he experienced in questioning American involvement in Vietnam and his place in it.

Although I did not have the good fortune of interviewing Mr. Ehrhart about his service and role in the documentary series, his interview for the series demonstrates a different approach to the series than Heaney. Mr. Heaney, who had taken a solemn approach to the series by assuming the representative role for his fallen comrades, is rather personable in the oral history interviews when compared with his role in The Vietnam War. Ehrhart, on the other hand, appears to have adopted a similar tone in both interviews. It would be incorrect to say that Mr. Heaney’s interview with Ken Burns was not emotional or reflective, but it is significant to note the ways in which Ehrhart tells his story in a deeply personal, emotional way.

EHRHART: Of course, all these civilians had been herded into the university. They had all gone there to get the hell away from having grenades thrown in their living rooms. And one of the guys comes in and says, “I found this, this girl who will fuck us all for C-rations.” And I’m thinking, “Wait, we’re in the middle of this big battle and I’m gonna go and- but I’m 19 years old and my buddies are gonna-" and I just, I demonstrated to myself how little courage I actually had. I’ve lived with it ever since, but I did it because I wasn’t gonna say, “You guys, we shouldn’t do something like this.” Even more than the killings, the thing I think I’m most ashamed of, when I think about the time I spent there. I think it’s because my mother’s a woman, my wife’s a woman, my daughter’s a woman. Somebody gets shot, not a good thing. You see somebody running away, well could have been a VC. That woman, nah. I had every opportunity to say no.

The remarkably personal and vulnerable manner in which Ehrhart covers this anecdote illuminate his comfort with being interviewed and sharing his story unabashedly. His narrative style operates on his command of honesty. This holds true for both the Hoffman and documentary interviews.

Ehrhart also employs a somewhat dark sense of humor to enliven his narrative, as well as provide reflections on the events he experienced in Vietnam. For example, when describing the disconnect between what was reported about American war prospects in the media and the reality he saw on the ground, Ehrhart humorously questions the claim that American successes had set back the Viet Cong by four months:

EHRHART: I mean, nobody told the Viet Cong that they’d been set back for four months. And yet this is what you’re reading in the newspapers.

Upon examining W.D. Ehrhart in both interview settings, his consistent tone and narrative style is noteworthy. Especially after considering the intentional manner in which Ken Burns and Lynn Novick went about finalizing their documentary series, that a man of Ehrhart’s verbal stature and life experience made it into the final cut is hardly surprising at all.