The Narrative Style of Mike Heaney

Comparing Mr. Heaney’s narrative style in oral histories to his storytelling for the documentary series interview requires breaking the interviews down by some essential characteristics: medium, tone, and rhetorical tools. Establishing these axes of distinctions is important in recognizing the disparate goals of oral history vs. documentary film.

Medium

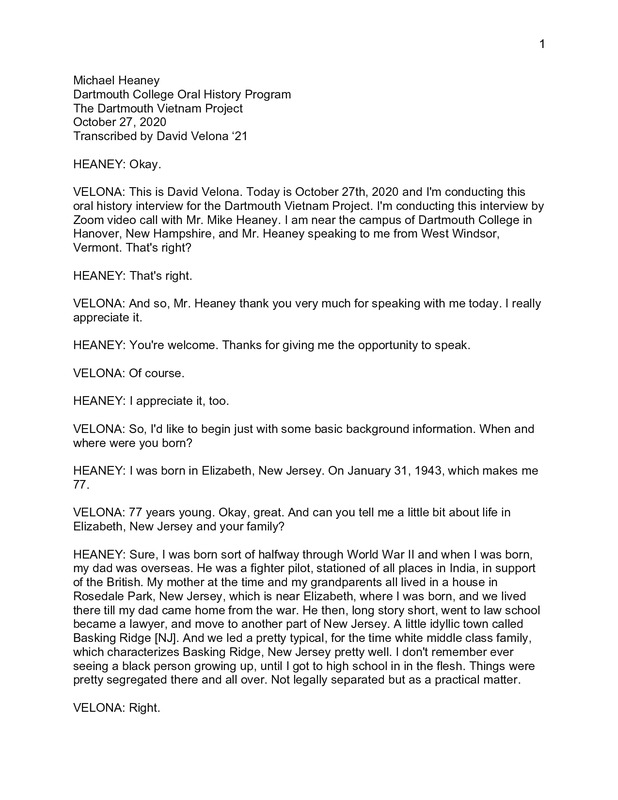

When examining Mr. Heaney’s interview with Ken Burns for The Vietnam War, the viewer is precisely that: a viewer. Because the interview was captured in an audio-visual format, viewers of his oral testimony are exposed to a very humanized narrative that allows engagement with Mr. Heaney’s facial expressions to match the tone of his narrative style. Although the interview for the Dartmouth Vietnam Project (DVP) was conducted over Zoom video call, it will only be released in audio and transcript form. This is the most obvious difference between the media of these two interviews, aside from their length.

Indeed, the broader goal of the documentary series was to collate several individual narratives and anecdotes about the Vietnam War into a larger collective, in order to tell the story of the war. The interview contains numerous interjections from a narrator to provide context and allow the interview to be used toward the broader goal of using multiple interview segments, rather than the immersion in single, extended narratives that oral history provides. In the clip linked to this page, one can see that the interview is segmented by footage from Vietnam, context from the narrator, and even sound effects. This editorial approach to stylizing the interview in order to increase the viewer’s engagement with the narrative would neither be appropriate nor necessary in an oral history interview. Although the intentions of Mr. Heaney with respect to The Vietnam War interview are not absolutely established, my interview with him may illuminate his approach.

HEANEY: […]this is definitely a mission of mine in life. One of my life's missions. One of the few. I was so close to those guys. They were such good guys. They deserve a voice and I want to do what I can to give them a voice.

Despite the fact that Mr. Heaney expressed some qualms about the film’s shortcomings with regard to an academic interpretation and study of the Vietnam War (since returning home from Vietnam, Mr. Heaney became a Professor of History at Trinity College), he viewed his participation in the series as a chance to tell the story of his men who could not do so for themselves. His calm, somber tone in the documentary makes this intention clear.

Tone

The most striking contrast between Mr. Heaney’s narrative style in our Dartmouth Vietnam Project interview and for the documentary series is his tone. Perhaps the most common non-verbal feature of the interview transcript, which is below, is the inclusion of “[laughter]”. Mr. Heaney employed his sense of humor as a particularly effective element of his tone throughout our interview. Although the interview will be available to the public and posterity via The Dartmouth Vietnam Project’s digital archive, the context of our interview was not weighted with the watchful eyes of millions. Either this fact or his increased comfort with the narrative suggests the possibility that Mr. Heaney was more relaxed in his oral history interviews compared with the PBS documentary series. Indeed, the gravity of his life’s mission, mentioned above, is also relevant when considering the tone he adopts for the different interviews.

To explore this difference in tone, it is useful to compare one particular anecdote he tells in both interviews. During the ambush in An Khe, Mr. Heaney made a pact with God regarding the lives of his men, as well as his own. Here is a transcript excerpt of how he tells this story in the documentary series:

HEANEY: "If you need any more guys from my platoon, take me. Don’t take any more of my men." As soon as I said it, I freaked myself out and said, "Holy shit. Can I take that prayer back?" But it was too late, I’d said it and as it turns out, not one more man of my platoon died after that prayer.

In this excerpt, Mr. Heaney clearly conveys a sense of regret for having offered his own life to God. Without much reflection on this, he proceeds to tell the viewer about the apparent consequences of this pact, namely that no more of his men perished. His tone, available for consultation in the video clip at the bottom of this page, is rather somber and serious, which pulls the viewer into the gravity of the situation he experienced in this ambush in 1966.

With the tone of his recounting this story in the documentary series in mind, here is how Mr. Heaney tells it in our DVP interview, conducted on October 27, 2020:

HEANEY: Oh, and I had my talk with God. I didn't tell anybody that story for years because it sounded like I was blowing my own trumpet. And I didn't feel that way at the time, whatever maybe the truth of that. I felt like that was my best bet. [laughter]

So, I told God - and maybe you've read this somewhere. I've told it now in the last, you know, 12 or 13 years. I said, "Okay, this is what we're going to do. And if you have to take any more of my guys, any more from my platoon, take me because they've given enough. And I don't want to lose any more." And I finished that little announcement [laughter] and said, "Now, what the hell have you done, Michael? Can I have that back, God?" And, of course, nobody answered. Not right then, anyway.

In this excerpt, Mr. Heaney laughs twice while recounting this serious pact made with God. Not only does he impart the actualities of this conversation with a higher power, but he also reflects on his relationship to the narrative itself, specifically that he was wary of including it in his earlier tellings of the story, out of fear that he might seem to think too highly of himself. Just the intentional omission of this part of the story of the ambush in previous iterations suggests that as one tells and retells a personal narrative, their relationship to it changes. In this case, Mr. Heaney conveys that his relationship to the narrative concerned the potentially judgmental thoughts of others, which he eventually learned to discard in favor of a truer narrative. Additionally, perhaps due to the more personal circumstances in which our interview was conducted, as compared to the highly public nature of the PBS series, Mr. Heaney gives a glimpse into his own mind.

Rhetorical Tools

A stylistic similarity that Heaney employs in both oral history and documentary interviews is his use of the first-person historical present to convey his thoughts at the moment of what he is recounting. While this rhetorical strategy is not necessarily a conscious one, it speaks to Mr. Heaney’s storytelling abilities that undoubtedly earned him a place in the final version of the documentary series and that made our interview so engaging.

In The Vietnam War, Heaney describes his thoughts about a fallen Vietnamese soldier lying on the ground next to him, whom he feared was still alive.

HEANEY: “This guy’s gonna kill me. He’s faking it, he’s waiting until the assault, then he’s gonna jump up and kill me.”

In our interview, Mr. Heaney employed this same storytelling device when discussing his close encounter with the dead Vietnamese soldier inside their perimeter.

HEANEY: I remember seeing a dead North Vietnamese soldier on my path that I was crawling along to get to the perimeter. I couldn't see any wounds on him, and I thought he was, for a minute, I thought, "He's still alive. He's waiting until I crawl past him and he's going to shoot me. So maybe I should shoot him again." I said, "That's ridiculous. You'd be shooting a dead man. You're just gonna scare everybody." And so I gave up that idea. And the guy was dead, so that worked out okay. [laughter]

Again, Mr. Heaney uses this same strategy in recounting this experience for his oral history interview with Kelly Crager, an oral historian from Texas Tech University. It should be noted that his interview with Dr. Crager, similar to his interview with me, is marked by his frequent laughter.

HEANEY: He had no visible wound, although he seemed clearly dead. And I said to myself, “Maybe you’d better shoot him again because you’re lying right next to him.” And then I said to myself, “You know, that’s really stupid. That’s really grotesque, shooting a corpse.” So ultimately, I didn’t do it, but I thought about it. Ultimately it really freaked me out [laughter], having this dead guy lying right there next to me.

Especially after examining the difference in tone between the two kinds of interviews, his strategy of using the first-person historical present to give his audience access to his thoughts at the time, is effective. Whether he tells the story with a smile or a more serious face, Mr. Heaney demonstrates some level of consistency in his narrative style.

Despite this strategy appearing across the board, much like his tone, Mr. Heaney’s use of rhetorical tools is different in his documentary interview as compared to oral histories. A significant feature of the documentary interview segment (below) is his use of the first-person plural, “we” and “us,” when referring to his unit, their role in the war, and their specific mission assignments. His consistent use of the first-person plural conveys the goal for participating in the documentary series that he expressed in our interview, namely to tell the stories for the men who no longer have a voice. In the documentary interview, he says things like “We’d go through a village, in which there would be no people we could identify as enemy soldiers, and we’d find a big cache of rice” and “Our hearts really weren’t in trying to destroy civilian food, civilian homes.” Mr. Heaney uses this first-person plural to describe both the matter-of-fact orders his unit was given, as well as their collective thoughts on the orders. As he was, in a sense, speaking for the men he commanded in Vietnam, whether they survived the war or not, Mr. Heaney’s focus is on conveying a more collective sense of their experience as a unit, as opposed to the more personal nature of oral history testimony.

In our interview, Mr. Heaney used the first-person plural to a much lesser extent. As discussed above, the fact that he adopted a more serious tone for the documentary series is in line with his desire to speak for others, as well as the perceived stakes of working on such a significant project. Since his focus was more directed at telling his own story and reflecting on the experience of telling the narrative so many times, his interview with the Dartmouth Vietnam Project is more centered around his personal experiences, as well as his own interpretations of them.

To listen to my full interview with Mr. Heaney, please click here.