"Witch Hunts"

Even as some lesbian women found a form of "sanctuary," there always loomed the possibility of a dishonorable discharge for being discovered in one of the routine "witch hunts."

This specific form of discrimination against gay women was relatively new during the Vietnam war era. Until the end of World War II, lesbians in the military were largely disregarded, especially relative to their male counterparts. The civilian world mirrored this tacit acceptance of romantic relationships between women. Margot Canaday found that in New York City in the 1940s and 1950s, while thousands of men were convicted for "homosexual activity," only three women were arrested for the same charge, all of whose cases were dismissed. Military officials were aware of yet not overtly punitive towards physical relationships between women. However, women's social advancement and increasing prominence in the military combined with Cold War paranoia to produce an "anti-lesbian" apparatus specific in its targeting of gay women. Lesbians were seen as secretive and strategic relative to gay men. Myths proliferated about "queen mothers" that were "established lesbian[s] who [were] the leaders of a female homosexual ring" that "may or may not have [sex] relations with the other members of the ring." In 1955, military officials uncovered a supposed subversive international cabal of lesbians called the "United Association of Gay Girls in the Armed Forces" (Canaday 2009). Enforcing the ban on lesbian women relied on new techniques of extreme surveillance and repeated interrogation. These tactics ensnared entire women's social networks. and stayed in place for decades to come. Before, during, and after the Vietnam War, military officials struggled to definitively prove lesbianism. Instead, they waged a war of persistence until the women confessed, if only to end the humiliation of the investigation.

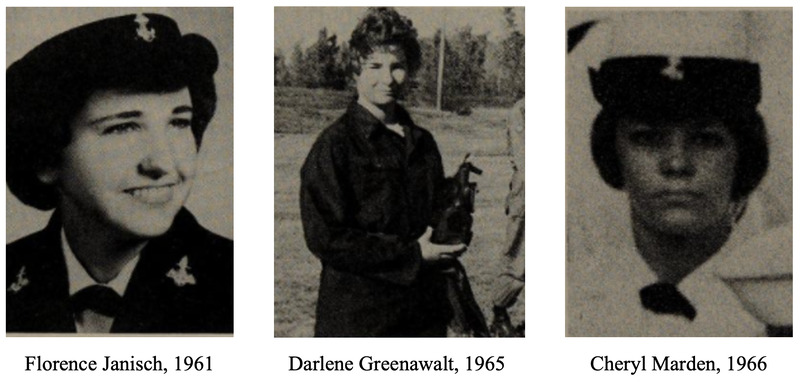

For the women whose sexuality came under disciplinary scrutiny, the suffering lay both in the trauma of the investigation itself and the subsequent loss of formal benefits and the community they had created. Darlene Greenawalt rejected the advances of a female officer, who then reported her. Eventually, she wound up in the hospital on "tranquilizers" due to the stress of the investigation, "I was just losing it all over the place." Ruth Hughes managed to talk her way out of an accusation after her sister wrote a letter to the military authorities outing her as a lesbian. Hughes recalls that military authorities had an "incredible list of names, addresses, and telephone numbers, Not just people I had been sexually involved with but all women I knew." In part, Florence Janisch was given away because she owned a copy of The Women's Barracks by Tereska Torres. The novel established the genre of lesbian pulp. The House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials had banned the novel in 1952 for "promoting moral degeneracy." For this infraction, a set of male officers interrogated Janisch and her partner with a slew of graphic, invasive lines of questioning. "It was a no-win situation." Janisch's relationship was made out to be a "dirty, sick, unnatural union." After a dishonorable discharge, women lived in constant fear that employers would learn about their dismissal. At the end of her interview, Janisch says, "I'm still paranoid about someone checking into my Navy background and finding out about my undesirable discharge." Darlene Greenawalt, who initially turned to alcohol, began attending "group and private counseling, trying to resolve [her] feelings involving self-worth, esteem, and [her] devastating military experience."

While all these women served in different times and different places, a single unifying factor in their experience is the environment of constant risk that authorities might discover their sexual orientation. Hughes described this experience as "absolute terror." Kathy Reynolds put it in comparatively benign terms when she said,

However, even as some women could live with this baseline risk, the secrets took a toll over time. "Janice" ended her interview on the note,

Systematic erasure of their identity created a unique type of trauma, even as these women were also confronted by the stresses of war. When asked whether she believes she carries any lingering trauma from her time in the war, Ms. Reynolds replied,

While many Vietnam-era nurses carry heavy memories of their patient's injuries, Ms. Reynolds' time in the military created an intolerance for people who, "try to make [themselves] into something [they] aren't."

Conclusion

At the beginning of his 1993 book, Conduct Unbecoming: Lesbians and Gays in the U.S. Military Vietnam to the Persian Gulf, journalist Randy Shilts said,

This exhibit outlined some of the ways in which this attitude manifested in the lives of LGBTQ servicewomen during the Vietnam era. The ban on gay service people often did little to deter them from joining, and many had very successful formal careers in the military. Today, stories like these remain under-documented, even in the field of oral history. The hostility towards gay service people and the relative lack of recognition of their service represent an underacknowledged stain on the history of the United States armed forces'.