Seabees as "Goodwill Ambassadors"

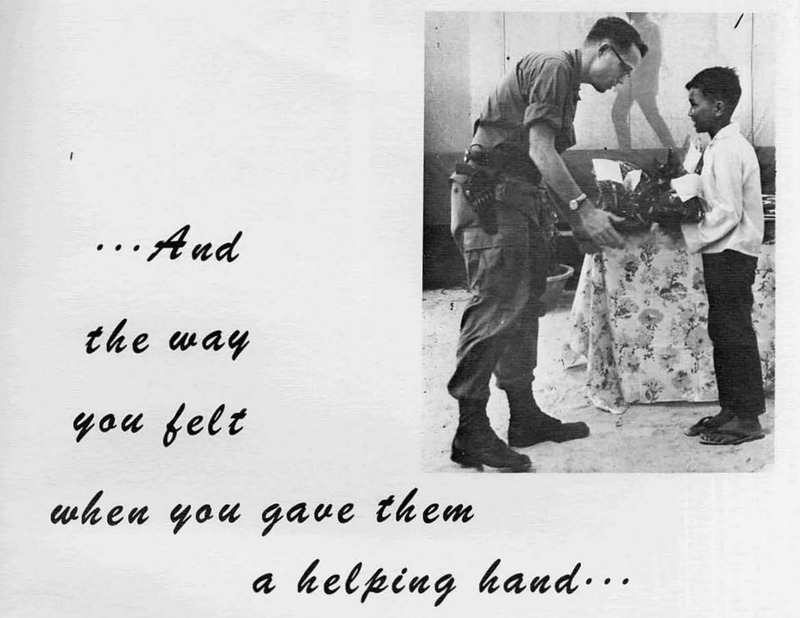

Seabees were expected to act as “goodwill ambassadors,” as they offered their humanitarian aid to their fellow Vietnamese villagers and locals. Historian Laura Godbille argues that the Seabees provided indispensable significance, noting that “in a war where winning the hearts of the people was an important part of the total effort, Seabee construction skills… proved powerful weapons in the Vietnam ‘civic action’ war.” Although civic action entailed varying responsibilities and projects, civic action manifested itself many times, through two avenues: construction projects, and construction training for local Vietnamese inhabitants.

Building Infrastructure:

Robert Sletten’s oral history conveys the wide gamut of projects that many Seabees undertook as part of civic action missions. For instance, in addition to rice warehouses, his Seabee Team 7102 also built farm-to-market roads and related road improvements. Although often overlooked in military histories of the war, such projects provided potential benefits to Vietnamese villagers. By exploiting these road improvements, farmers who otherwise would not have been able to easily access a market to sell their crops for profit could potentially move beyond subsistence farming.

According to Sletten, performing civic action missions provided him and his fellow Seabees a level of protection and security that other US military counterparts did not enjoy. Sletten explains that he and his men felt relatively safe, even in areas where Viet Cong clandestine operatives were believed to be present:

“And it was because, I think, of the kind of work that we did. And the fact that we were relatively non-threatening. We were actually helping people in villages with buildings, farm to market roads, rice warehouses, things that were intended to improve their life. And I think to a certain degree, that gave us some insulation from really being bothered.”

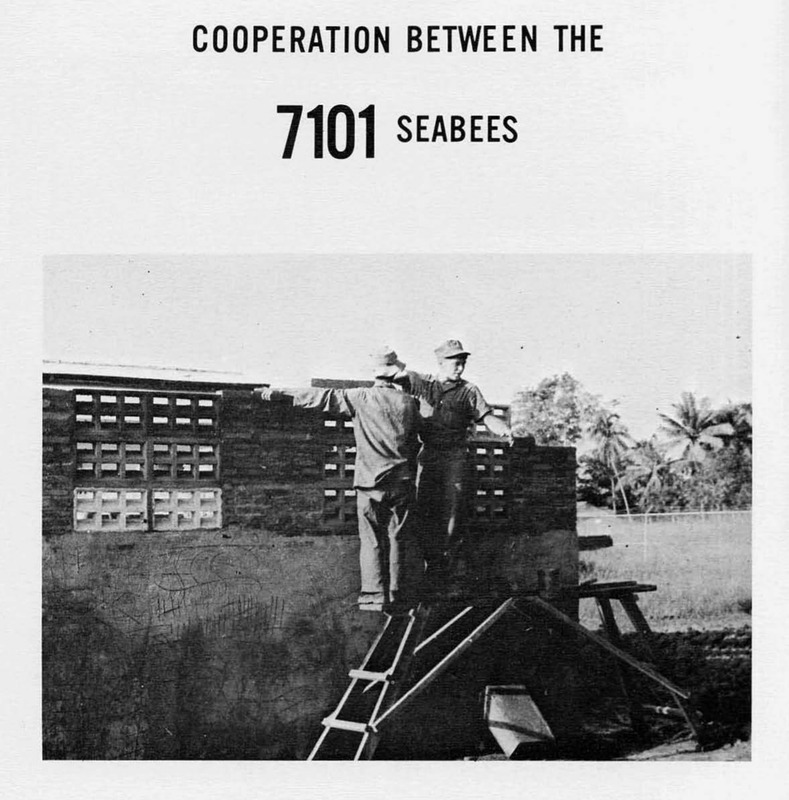

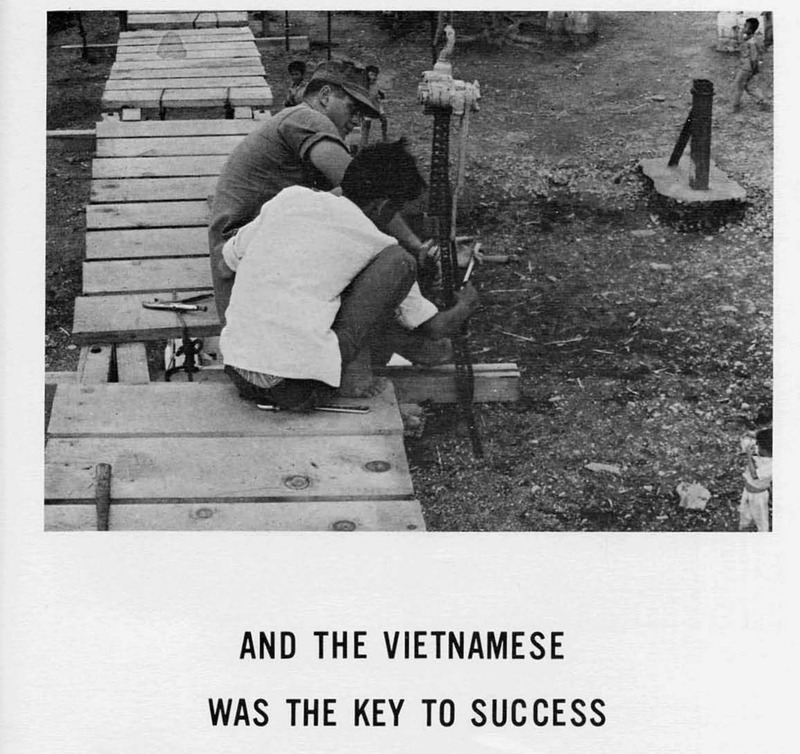

Training the Vietnamese Construction Skills:

In addition to construction projects, Seabees also trained Vietnamese in construction trades, with the aim of providing valuable skills that local residents could use after the Seabees’ departures. Laura Godbille expands on this sector of civic action, explaining that this on-the-job training to the local population aimed to “teach the Vietnamese basic construction skills so that they would have the future capability to duplicate the types of projects accomplished by the teams.” For his Seabee Team, Sletten recalls training programs for welding, mechanics, equipment operation, and electrical work.

Sletten’s oral history includes his experience with the Chieu Hoi ralliers program (also known as the “open arms” program) which encouraged enemy soldiers to desert from the “Viet Cong” and North Vietnamese Army forces and defect to the South Vietnamese government side. Under the program, these defectors were trained in practical fields, such as agriculture or other construction trades, and then settled in local communities. In his memoir, Rufus Phillips reports that a total of about 200,000 Vietnamese rallied to the anti-communist side over the course of the war.

Relationships Forged, or the Lack Thereof:

Seabees worked closely and extensively with Vietnamese local residents in the course of conducting their civic action mission. Under the strategic proposal to win hearts and minds, these collaborations were not a mere afterthought or consequence of civic action missions. In fact, Vietnamese-American cooperation on civic action was viewed by US leaders as essential to the overall success of the Seabees’ mission.

Many Seabees remember forging positive and optimistic relationships with their Vietnamese counterparts. During his second tour, Sletten became familiar with Alfred Lamy, the Seabee Team’s interpreter, along with the Seabee Team in-house cook, whom he (and his fellow Seabees) referred to as Mama-San. During our interview, he warmly reflected on Lamy’s young and rambunctious temperament, and on Mama-San’s motherly nature.

In another oral history, Louis Cavicchioli, a former Navy Seabee, claimed that he and his colleagues were well-situated to build friendly and trusting relationships with Vietnamese local residents:

“We were really close to the villagers– the Seabees were… The Marines had a different view of them because they were fighting people… the fighting forces probably didn’t have as much trust in the Vietnamese as we did with the Seabees, because we saw these people day-to-day. I mean, I had pictures with the villagers and all that– I got along good with them… I used to have lunch with the villagers. I used to eat what they ate– dog… We got along good with them, that’s because our programs were, even with Special Forces at the time, was to gain their friendship and support of the villagers… Instead of fighting these people, let them become part of it. Teach them, train ‘em, integrate them into what you’re doing… We were teaching them how to live their life better…”

On the other hand, Seabee-Vietnamese experiences were not always positive. William “Bill” Culotta, a former Seabee who served in the same Mobile Construction Battalion as Sletten (MCB-71), understood his relationships with the Vietnamese to be fraught with uncomfortable political tensions that were unavoidable, no matter how polite or helpful either side tried to be. In his oral history, Culotta notes:

“Yeah, I had some interactions with some very, very nice Vietnamese families, very nice people... I think all of us felt a little awkward. I felt guilty for being in their country, and they [Vietnamese] were trying to be nice to somebody who was nice to them. So it was kind of weird.”

While most Seabees remember their interactions with Vietnamese as mostly peaceful, some remember occasional acts of violence committed by Americans against Vietnamese. In his oral history, Sletten recalls an episode of alarming and seemingly unprovoked violence:

“The first time you know, it was, the people were just there and there was a lot of callousness on the part of the Americans toward the Vietnamese. In fact, I hate to say it, but even some of our people. We were stuck down in this little place. So after things were a little bit stable, we would on Sunday afternoons, we would go, go ahead and send up a liberty party to the big city out at Phu Bai Base, you know, where they had an exchange and you could get a hot meal and stuff like that. And that was fine and of course they had clubs, so people could drink. [inaudible] Have drinking at our place and that was fine until you know, after three or four of those trips, somebody started– one of the Seabees started shooting up the countryside, you know, so he just– you know, he was drunk and he got properly chastised. But that ended the trips up there. And I guess I bring it up just to kind of demonstrate that on the part of a lot of people there was a fairly callous attitude and, you know, any Vietnamese was potentially an enemy and not to be trusted. And the second time that I was over there that attitude very much evaporated because we worked so closely with the Vietnamese and I got to like them as a people, very much.”

Charged with political, ideological, and cultural tensions, Seabees assumed a massive undertaking that wielded the power to galvanize the population, defend against communist insurgents, and enact lasting change. Whether or not these ultimate goals were accomplished or could have been accomplished (given more investment in time and money), is a point of contention. However, as the next page will explain, it becomes clear that to many of these Seabees, the boundaries of their commitment produced shortcomings of their civic action aid.