"Winning Hearts and Minds": Counterinsurgency and the History of Civic Action

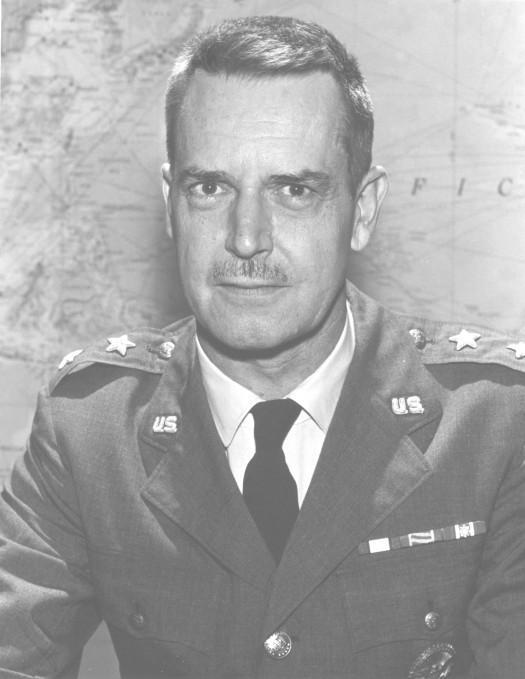

Placing the Seabees within the larger historical framework of the time explains their raison d’être in Vietnam. Many of the key missions that Seabees undertook in Vietnam were inspired by the idea of civic action, a concept associated with the theory and practice of counterinsurgency. While many intelligence specialists and strategists played a part in the early history of U.S. civic action operations after World War II, and the beginning of the Cold War, one of the most notable figures was Edward Lansdale.

Counterinsurgency’s Roots: Edward Lansdale in the Philippines

Edward Lansdale was a distinguished leader in the Philippines for developing unconventional warfare strategies against the rising communist rebellion group, the Huks, and Lansdale rose to prominence with his development of counterinsurgency campaigns. In the introduction to his memoir, In the Midst of Wars: An American’s Mission to Southeast Asia, his successes are presented: “...Lansdale found the nation ill and tottering, drained by political leeches, bloodied by an internal insurgent conflict. He left it strong and whole, under the guidance of a magnificent leader. In those years, from 1950 to 1954, Lansdale formulated his views on how to contend successfully against insurgent movement.” How did Lansdale effectively manage to squash a growing communist threat in the Philippines?

Under Lansdale’s philosophy, his decision to spearhead alternate methods of counterattack rather than relying on conventional tactics was the key to defeating the communist Huks. Including psychological warfare, civic action campaigns, and nation-building techniques, Lansdale believed counterinsurgency campaigns effectively combated the perils of communism. More specifically, Lansdale championed the power of civic action, coining the term:

“...CAO (Civil Affairs Office) set out to make the soldiers behave as the brothers and protectors of the people in their everyday military operations, replacing the arrogance of the military at highway checkpoints or in village searches with courteous manners and striving to stop the age-old soldier’s habit of stealing chickens and pigs from the farmers. As a descriptive term for this brotherly behavior, I dubbed it ‘civic action.’ The name stuck and later was adopted by armies in many countries.”

Lansdale envisioned the U.S. military to take an active stance in civilian affairs, and he underscored the benefits of civic action missions. By talking to individuals, observing first-hand the struggles of conflict, and forming individual relationships with local populations, it acted as a persuasive method for garnering support. Lansdale adamantly believed that this method of "winning hearts and minds" could topple a communist insurgency. For Lansdale, he believed that these tactics could convince the population that their lives had the potential to drastically improve through the suppression of insurgency at the local levels of society. These strategies became quickly adopted into the umbrella of counterinsurgency.

Laura Godbille’s “Following the Money: The U.S. Navy Seabee Teams and Military Civic Action in South Vietnam, 1963-1972” illustrates the approach to counterinsurgency: “Successful counterinsurgency could not be achieved arbitrarily, rather it depended on a compelling strategic concept that carefully combined and coordinated all aspects civic, political, economic, and military operations, unlike conventional Western war strategies which focused on a defined battle line…” indicating that counterinsurgency involved a much bigger, generalized scope of military and civic involvement to prove effective. This was the only way, according to Lansdale, to provide a strong foundation of a national political structure that had the support to resist the growing menace that communism presented.

After claiming victory against the Huks in the Philippines, Lansdale was reassigned to South Vietnam in 1954. By implementing similar tactics to win the hearts and minds of the local Vietnamese population, Lansdale and other leaders dove headfirst into several counterinsurgency campaigns, also known as pacification. Here, it is critical to mention that it was not Lansdale alone who supported these programs, bordering the years of his service, between 1954 and 1956. These concepts of civic action missions would even be continued by the Kennedy administration in the early 1960s, in the continuation of Cold War fears of communist domination. President John F. Kennedy chose to prioritize social and intellectual crusades over military action amidst the Cold War, and Kennedy’s ideas on countering communism was manifested in his belief that by fostering nation-building techniques of South Vietnam, guerrilla insurgents could be forcefully quelled. In fact, “fascinated by the potential of counterinsurgency, Kennedy was convinced that it was the key to American success in supporting wars of national liberation and popular uprisings.”

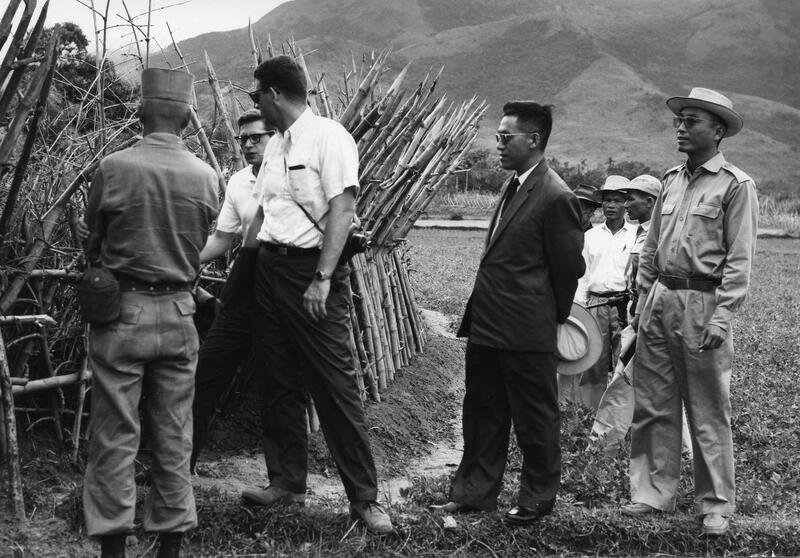

The Promise of Civic Action: Rufus Phillips

One prominent figure who strongly advocated Lansdale’s ideas in Vietnam is Rufus Phillips, an instrumental player in counterinsurgency and civic action campaigns in South Vietnam. In his memoir, Why Vietnam Matters: An Eyewitness Account of Lessons Not Learned, Phillips provides crucial insights into the philosophy behind his approach to counterinsurgency. For instance, Phillips introduces the general idea, noting:

“Rudimentary public services reached the province and district level but were nonexistent in the villages. Most villages had communal lands from which the village councils traditionally derived some rent, but it was not enough to meet their public-health, education, or public-works needs, and this system had been disturbed by the war. Civic Action, by working directly in the villages and meeting immediate public needs, would give the village renewed importance and fill this vacuum… Civic Action teams would provide the resources they lacked. As village needs became known and public services better organized, firmer links could be fostered between the villages and rest of the government. Then Civic Action would no longer be needed.”

Pacification experts such as Phillips saw civic action missions as an effective way to bolster nation-building and encourage Vietnamese-American alliances. Intricately connected to counterinsurgency campaigns to help nation-building, civic action missions included public works projects and construction assignments to directly benefit the local Vietnamese population residing in nearby villages. By building roads, bridges, rice warehouses, and other forms of infrastructure, American and South Vietnamese government intended their aid to be perceived as largely humanitarian and philanthropic. Lansdale mentions in his memoir that the local South Vietnamese responded positively to the friendliness of the South Vietnamese government forces, as it was “impossible to remain aloof in the face of so much willingness to help, so much evidence that someone really cared about them.” These reactions reaped positive benefits; the local Vietnamese would then voluntarily “reveal the location of secret caches of weapons and ammunition, [to] give names of those in Vietminh stay-behind organizations, and [to] pitch in to work alongside the soldiers in rebuilding and repairing destroyed or neglected public structures.”

Inspired by the promise of what civic action could do for the local populations, Phillips maintains an adamant faith that these campaigns’ possible successes could have changed the entire outcome of the war for the better, if it had been more competently led and administered. For Phillips, the struggle to win loyalty and support of rural populations with these campaigns was “the other war, the real war.” And in fact, he expounds:

“We failed to understand the ‘x factor’– the political and psychological nature of the struggle for the ‘hearts and minds,’ the feelings of the Vietnamese people… counterinsurgency effectiveness comes down to… acknowledging that the ultimate contest is not for physical terrain on the conventional battlefield but for the feelings of the civilian population…”

The Mythology of Counterinsurgency: Douglas Porch's Critique

Both Lansdale and Phillips’ philosophy on the potential power of these counterinsurgency and civic action campaigns represents the myriad of historians and experts who contend that had more time, energy, and resources been invested in this “other war,” the outcome of the Vietnam War may have been different. This revisionist perspective contrasts sharply with other perspectives, like Douglas Porch’s. Douglas Porch, in his Counterinsurgency: Exposing the Myths of the New Way of War, proposes the notion that counterinsurgency was a doctrine advocated by central actors like Lansdale and Phillips to be an expression of true, democratic values, when according to Porch, counterinsurgency was actually a doctrine practiced by Western forces in non-white societies, violating those liberal principles instead of upholding them. Specifically, he confronts counterinsurgency as a mythologized idealization of alternate warfare that could not have been the answer to defeating the North Vietnamese. He states, that “hearts and minds was very difficult to sustain, and extremely vulnerable to provocation,” and that “population-centric pacification– that is, protecting the population and winning their loyalty with civic action, hearts and minds programs– as a stand-alone operational and tactical approach never offered a war-winning strategy in Vietnam…”

Unlike Rufus Phillips who adamantly believes in the power of counterinsurgency as a critical component of victory, Douglas Porch deviates from that stance, providing the assessment that counterinsurgency is a romanticized, mythologized form of warfare that violates the democratic principles valued by Western power. He explains:

“COIN [counterinsurgency] offers a doctrine of escapism for many relevant personalities and institutions– a flight from democratic civilian control, even from modernity, into an anachronistic, romanticized, Orientalist vision that projects quintessentially Western values, and Western prejudices, onto non-Western societies.”

According to Porch, by inserting Westernized, liberal values onto the Vietnamese population, counterinsurgency was more an Orientalist, colonialist assignment than an essential aspect of victory in the war. This tension is reflected in many of the veterans’ post-war reflections, as they acutely discern the discrepancy in the shortcomings of their service in spite of good will and intent, as explored further in the last page.

These two camps of historical post-war analyses provide valuable insight into the post-war reflections of service as a niche source of support in Vietnam. They comprised a cohort of servicemen who actively engaged in many civic action missions as part of a larger war effort during the conflict. Though they were not the only ones to carry out civic action missions, these Seabees were the men who observed firsthand the impacts of their aid– both the possibilities of their achievements, and the shortcomings and limitations of their aid. Nevertheless, by building roads and warehouses, by teaching Vietnamese locals valuable skills and crafts, and by understanding individualized experiences of the Vietnamese, these Seabees were characters at the forefront of what could emanate from civic action missions.