The Narrative Style of Vincent Okamoto

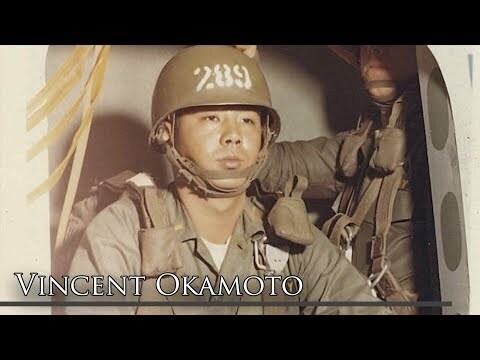

Vincent Okamoto, the most highly decorated Japanese American from the Vietnam War, was born in a Japanese internment camp during World War II. His brothers served in the military and Mr. Okamoto joined the ROTC program at UCLA for the last two years of his college. After graduation, Mr. Okamoto attended Ranger School and was deployed to Vietnam from 1968-1969.

While serving in Vietnam, his unit was ambushed by a large force of North Vietnamese soldiers on August 24, 1968, which is a main focus of his interview with the American Veterans Center. Okamoto personally manned the machine guns of three armored personnel carriers until they ran out of ammunition and eventually the assault ended with daybreak, by which point he had been wounded by grenade shrapnel. After recovering from his wounds, Okamoto became an intelligence officer for the company and was involved in the Phoenix Program. The Phoenix Program rested on the idea that North Vietnamese communists needed local support in order to carry out their war efforts against the United States. The purpose of the program was to identify, interrogate, and eliminate Vietnamese civilians and Viet Cong operatives who aided the communists. It is considered a highly controversial program on account of the brutal manner in which it was carried out and its effects on civilian life. After returning home from Vietnam, Okamoto pursued a career in law and eventually became a Superior Court Judge in Los Angeles, California.

His narrative style, as seen through this oral history interview with the American Veterans Center and in his role in the documentary series, is marked by a rather matter-of-fact demeanor, vivid detail, and a frank, dark sense of humor. Indeed, even when he is not using a particularly humorous turn of phrase or telling a joke, Okamoto appears dignified, proud, and slightly tongue-in-cheek in the interviews.

Similar to Mr. Ehrhart, Mr. Okamoto conducts his narrative style in a fairly similar manner in both interviews. In his interview for the American Veterans Center, Okamoto is wearing his medals and is in front of a memorialized backdrop. As the audience for this interview is likely other veterans, Okamoto emphasizes that to which others could relate, for instance how “awesome” the 50 caliber machine guns he used in the ambush were. This is an effective narrative style in terms of relating to his audience. On the whole, however, he carries himself similarly in both interviews.

The most notable consistency across the two interviews concerns his unique sense of humor. Just as Mr. Heaney employed his sense of humor throughout my interview with him, Okamoto does so as well. But rather than telling jokes or laughing to lighten the mood, Okamoto’s use of his humor suggests a cold level of comfort with his own narrative. In some instances it is difficult to ascertain whether his unique phrasing is intended to be humorous, descriptive, or to serve some kind of a shock value effect. What is clear, however, is the distinct weight behind his words. For example, Okamoto describes the devastated Northern sector of his company’s perimeter:

OKAMOTO: The two machine guns from the second platoon that was responsible for the Northern sector, they were hit with RPGs and grenades and a lot of the guys were just turned into long division problems. You knew who they were, but you wouldn’t recognize them.

Here, the key turn of phrase he uses is “long division problems,” as he references the American soldiers killed at the outset of the ambush. Okamoto’s descriptive phrasing draws on familiar knowledge on the part of his audience but requires the viewer to apply an intangible mathematical concept to the context of human dismemberment. Surely this is, in no way, a humorous subject matter, but it appears to be a conscious decision from Okamoto to establish his own comfort with the story, spread this comfort to his audience, and engage them with perplexing phrasing. Okamoto’s narrative style is brimming with this sort of curious language:

OKAMOTO: Second lieutenants in the infantry are kind of like being child molesters. No one likes them. Most of the men that you command have more time in country, or more experience. I had one guy come up to me on my first day, I was introducing myself to the men. And this one guy says, “You know, I’m not gonna bother to know your name, Lieutenant, because probably in the next couple weeks you’re gonna die anyway and we’ve had three platoon leaders in the last three months.” That was kind of bad for my morale.

In drawing this peculiar connection between infantry officers and child molesters, Okamoto once again calls on his audience to engage with his narrative by actively thinking about the connection he has made. Surely, as a former second lieutenant himself, Okamoto does not think the comparison to child molesters is literal, but he employs this humorous connection in order to get his point across, relay his own experience with this truth, and expose his viewers to a dark sense of humor that is typical in military service. However, this is an instance of Okamoto applying his sense of humor to an explanation of a broader aspect of military culture. He also engages his humor when discussing the grim realities of war. In the documentary series, while discussing his role as an intelligence officer in the Phoenix Program and how it operated, he says this:

OKAMOTO: The geniuses in Saigon would use their computers to come up with the blacklist. You get the list, and you check with other intelligence officers in the district, and you try to pool that information. Next night or a couple nights later, a bunch of cowboys from the PRUs would go out there and, you know, knock on the door, “April Fools’, motherfucker,” and BOOM. There wasn’t any real accountability.

His choice of words when describing the executions carried out by the South Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Units is, once again, curious. Okamoto’s use of humor, when combined with his curt phrasing, to share the story of this controversial program in which he took part, is, once again, curious. Just as he did with the “long division” phrasing, Okamoto calls on listeners to compare their own experiences with April Fools’ Day and apply it to this darker context of wartime execution. I believe his use of humor adds to the efficacy of his narrative style precisely because it is shocking.

When combined with his matter-of-fact demeanor, Okamoto’s vivid imagery and sense of humor make for an effective, even if confusing, narrative style. Just as with Mr. Ehrhart, after analyzing his narrative style, it is abundantly clear why he was chosen to be featured in the documentary series.