A Chance for Renewal: The 1986 World Cup Opening Ceremony

The opening sequence of the 1986 World Cup was a hopeful expression of the direction of Mexico. Created by the World Cup Committee with input from the state, the opening sequence worked to redefine the Mexican national identity. After the debt crisis and a humanitarian crisis, President Miguel de la Madrid and the PRI saw a chance to renew faith in the state and a chance to renew the identity of Mexico as a partner of a global economy. Though President de la Madrid and the PRI were able to throw the World Cup, Televisa and the Mexican state commodified the national identity of Mexico, particularly the indigenous identity, during the 1986 World Cup. The public grew increasingly discontent with this commodification, but the public discontent with the state and the PRI was fueled in the early 1970s.

In the 1970s, President Luis Echeverria took advantage of the lending offered to developing nations to build up state infrastructure and state-run organizations. This building of state infrastructure and state-run organizations was followed with President Jose Lopez Portillo coming into office in 1976 with continued borrowing to fund the state-run programs and ensure the political stability of Mexico. This period of heavy borrowing raised the Mexican national debt from $6.8 billion in 1972 to $58 billion in 1982. Rising interest rates caused this debt to crush the Mexican state, forcing Mexico to declare bankruptcy in August 1982. President Miguel de la Madrid, to ensure the survival of the state, privatized many state-run businesses, essentially creating an almost completely capitalist state. This neoliberal change was backed by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank—which subsequently bailed Mexico out on the terms it privatized most of the economy. In A Brief History of Neoliberalism, David Harvey discusses these changes but often does not discuss the attempts made by the Mexican state to limit the crisis on the government itself. These broad, sweeping changes forced austerity on the Mexican people, with particularly drastic changes occurring in Mexico City. Many were left unemployed with limited access to essentials, such as potable water, food, and shelter.

To compound the debt crisis for some, one of the largest earthquakes on record hit Mexico City on September 15, 1985. Thousands were killed and injured, with tens of thousands being left homeless. This event happened 284 days before the World Cup, with many questioning the state’s ability to run the World Cup and whether it would be able to fund the infrastructure repair necessary to ensure the World Cup would be successful. The Organizing Committee of the World Cup, however, put these concerns to rest to the international public by releasing statements ensuring the stadiums in Mexico City were viable to hold games. The Mexican public protested the World Cup because of the effects of the earthquake on the public, and the state funds being used for the World Cup were not being used for earthquake relief.

President de la Madrid made neoliberal changes to Mexico with the intention to help make Mexico an influential partner on the global stage. While the World Cup provided an opportunity for the state to depict themselves as a partner to the world, running a truly global competition, they had been working towards this through development of some of the institutions that became their downfall, as shown by Christy Thornton. Mexico had positioned themselves as the leaders of Latin America, establishing economic sovereignty prior to 1972 after the Mexican Revolution. The excessive borrowing and defaulting of their loans, however, forced Mexico to prove themselves once again as a leader in Latin America through the World Cup. This frame in particular references this global partnership through the handshake of two different people with the world’s flags in the background. By painting Mexico as a global partner once again, the state was trying to show Mexico was ready for a leadership role in Latin America particularly, the partner of the United States in ensuring the continued success of the neoliberal model championed by the two countries.

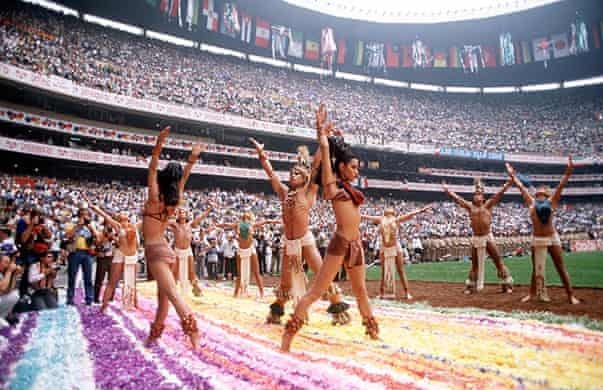

Though Mexico was dealing with the fallout from the debt crisis and the 1985 earthquake, the state wanted to shape the image of Mexico to be seen as a strong member of the international community. President de la Madrid and the Organizing Committee for the World Cup saw the World Cup and its opening ceremony as an opportunity to reshape the national and international view of Mexico. The image of the Mayan pyramid with the sun rising behind it from the opening sequence of World Cup broadcasts was used to reshape the identity of Mexico. The indigenous past of Mexico is often commodified and used to portray a past, stagnant version of Mexico, but many Mexican officials and intellectuals saw the indigenous identity of Mexico should be subsumed by the European ties of Mexico. In José Vasconcelos’ The Cosmic Race, Vasconcelos acknowledges the indigenous past of Mexico, but believes the European portion of the Mexican identity is superior. The recognition and destruction of indigenous history and identity was used during the Opening Sequence by recognizing the indigenous past of Mexico but moving past it immediately, with this frame only lasting a few seconds. As expressed by A.S. Dillingham in Oaxaca Resurgent, the state often recognized indigenous past, but refused to allow indigeneity to be pervasive in what the state saw as Mexican national identity going forward. The state wanted to ensure the indigenous identity of Mexico was commodified, without allowing indigeneity to be significant in the Mexican identity.

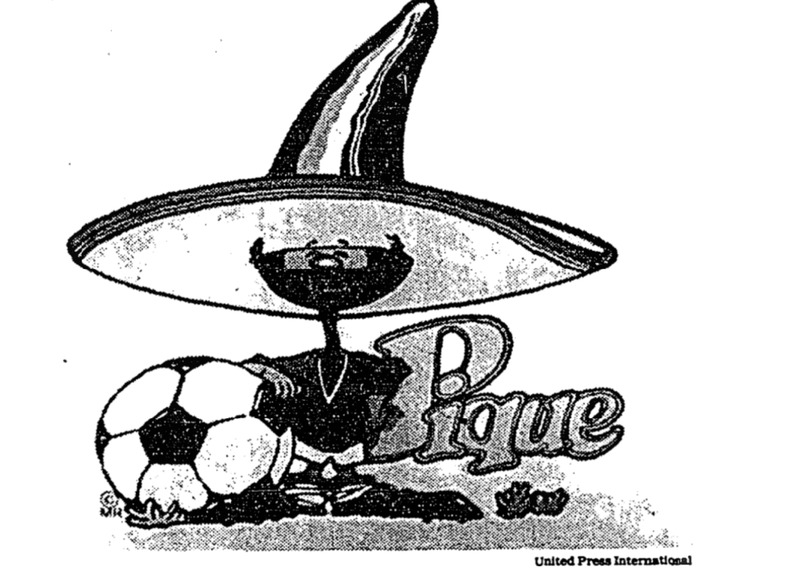

The identity of Mexico was also commodified through merchandising and advertising in other ways, with one example being the caricature of Mexico, Pique. Pique is perhaps the most grotesque example of the commodification of the identity of Mexico. Many within Mexico, including some government officials, criticized Pique for being “like a 1930’s Hollywood image of Mexico.” The Mexican public decried Pique for this reason, feeling it was not an accurate representation of Mexican national identity. This particular commercialization of the Mexican identity was widely appealing to the international community, according to the head of press coverage Jose Munoz de Cote. The appeal to the international community was all to ensure the commodification of the Mexican national identity, with little regard for how the Mexican public reacted to the caricature of their identity.

The truth is that Pique is only a mascot and he's not going to create an image of Mexico. The people of Mexico will create that image.

Segundo Perez, Co-Creator of Pique

While Segundo Perez gives credit to the public for creating an image of Mexico in their own right, the commercialization of the national identity made it difficult for the public to move past caricatures such as Pique. This caricature of identity was a large part of the advertisement for the World Cup, but the mythologizing of the national identity during the Opening Ceremony performance helped to commodify the national identity further.

The performances were supposed to mythologize the national history of Mexico, with the performance having dress influenced by indigenous peoples and other cultural influences in Mexico. The interpretation of indigenous peoples commodified indigeneity heavily. The national identity of Mexico was being constructed by the Organizing Committee and the state during the Opening Ceremonies, those within the stadium were disquieted by the state’s handling of other events. While the state promised all these events would be privately funded, which proved largely true, almost none of the funds benefitted the public. According to the industry estimates Televisa made approximately $26 million in service and rental fees and advertising revenues. The revenue generated was a clear indicator of the commodification of the Mexican identity, particularly involving the indigenous populations of Mexico during the opening sequence and ceremony of the World Cup. The discontent of the Mexican public with this, even without knowing the industry estimates of profit, was shown during President de la Madrid's Opening Ceremony speech.

[President de la Madrid's] words were completely drowned out by boos and whistles. I was dying with embarrassment, but it seemed to be the right metaphor for the mood of the country.

Middle-ranking Mexican Official in Attendance of the Opening Ceremony

The unpopularity of President de la Madrid and the PRI through the booing of de la Madrid’s speech is a primary example of the failure of the Mexican state to redesign Mexico’s national identity and renew belief in the state. The attempts of the state towards renewal of the Mexican identity during the 1986 World Cup Opening Ceremony failed. The PRI had the chance to renew their popularity but were unable to because they focused too heavily on the World Cup and forgetting the people of Mexico. The people of Mexico, as mentioned by this middle-ranking official, showed the true discontent of the country, something the state had been trying to cover up through the World Cup. President de la Madrid opened the country to neoliberalism while closing off the PRI further from the Mexican public. The World Cup could have made a difference for the Mexican public, but President de la Madrid and the PRI made the World Cup a winning event for the elite, especially Televisa, the broadcaster owning the rights to airing the opening sequence and everything after.

Biliography:

AP. “Sports News Briefs; World Cup On Despite Quakes.” The New York Times, September 23, 1985, sec. Sports. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/23/sports/sports-news-briefs-world-cup-on-despite-quakes.html.

Dillingham, Alan Shane. Oaxaca Resurgent : Indigeneity, Development, and Inequality in Twentieth-Century Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2007.

Jr, William A. Orme. “World Cup Called Financial Winner.” Washington Post, June 29, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/06/29/world-cup-called-financial-winner/c5a154a9-6aa0-49c4-bc28-db0657a5485a/.

Lemoyne, James, and Special To the New York Times. “Rubble Sifted in Mexico, but Hopes Are Waning.” The New York Times, September 23, 1985, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/23/world/rubble-sifted-in-mexico-but-hopes-arre-waning.html.

Lenti, Paul. “Latin America-Broadcasting: Televisa Massing Soccer Cup Forces.” Variety (Archive: 1905-2000). Los Angeles, United States: Penske Business Corporation, March 12, 1986.

LLC, Translated by ContentEngine. “1986 World Cup | Mexico Was Standing.” CE Noticias Financieras, English Ed. May 28, 2021.

Mera Carrasco, Julio. Fútbol (la copa del mundo en sus manos). México: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, 1970.

Mifflin, Lawrie. “A Place for Soccer's World Cup.” The New York Times, May 8, 1983, sec. Sports. https://www.nytimes.com/1983/05/08/sports/a-place-for-soccer-s-world-cup.html.

Mifflin, Lawrie. “A Place for Soccer’s World Cup: Mexico Bid Seems The Strongest Place for Soccer’s World Cup.” New York Times. 1983, sec. Sports Special Long Island Automobile Exchange.

Mora, Adriana de la. “‘Voices of Mexico’ Issue 0 by Cisan Unam - Issue,” August 1986. https://issuu.com/cisan.unam/docs/vom00.

The New York Times. “Mexico World Cup Mascot: Not ‘Ole’ But ‘Oh No,’” May 12, 1984, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/12/world/mexico-world-cup-mascot-not-ole-but-oh-no.html.

Riding, Alan, and Special To the New York Times. “Mexicans, Hurt in the Oil Crisis, Turn Their Anger on De La Madrid.” The New York Times, June 25, 1986, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/25/world/mexicans-hurt-in-the-oil-crisis-turn-their-anger-on-de-la-madrid.html.

Thornton, Christy. Revolution in Development Mexico and the Governance of the Global Economy. First. University of California Press, 2021.

Treaster, Joseph B., and Special To the New York Times. “With Houses in Rubble, Thousands are Refugees in Their Hometown.” The New York Times, September 23, 1985, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/23/world/with-houses-in-rubble-thousands-are-refugees-in-their-hometown.html.

José Vasconcelos. The Cosmic Race, 1925.

The Guardian. “World Cup: Historical Opening Ceremonies and Opening Matches,” June 12, 2010, sec. Football. http://www.theguardian.com/football/gallery/2010/jun/12/world-cup-opening-ceremonies-matches.