1985: The Earth Shook, the Government Failed, Mexicans Took Action

The Pan American Health Organization’s documentary “Earthquake Mexico 1985” depicts people chanting, "We want to work and help,“ outside the collapsed Juarez Hospital in Mexico City. The hospital crumbled on September 19, 1985, trapping their relatives and medical staff in the rubble. However, the government did not provide people with any news updates on the collapse. More than 10,000 people died in the 8.1 magnitude earthquake, the majority of whom were trapped in the rubble, like in Juarez Hospital, dying slowly waiting for government rescue efforts. By verbally hearing the chant, one notices how brave and desperate people were in helping one another recover from the disaster in the face of danger. In this exhibit, I argue that the Mexico City Earthquake forced the people to act like a government because of President Miguel de la Madrid’s poor handling of the situation. The earthquake did not spark a new awareness of the government’s inadequacy but forced people into action. They could not pretend that life continued on because the earthquake interfered with their everyday lives.

The people of Mexico City were already aware of the government corruption and repression within the Institutional Revolutionary Party, also known as PRI. The party typically arrested forces that threatened their power. In the 1960s and 1970s, people organized efforts to revolt against the PRI in Mexico City. The Student Movement of 1968 began in the summer but ended in the Tlatelolco Massacre, where the government killed an estimated three hundred students protesting at the Plaza de Tres Culturas. When Luis Echeverría, the Secretary of the Interior believed to have ordered the massacre, became president in 1970, he worked with the paramilitary, the army, and other special forces to “disappear” activists. Groups like Centro Nacional de Comunicación Social (CENCOS) documented these abuses and fought for human rights along with the families of political prisoners. Eventually, in 1984, the Mexican Academy for Human Rights in Mexico City was created by lawyers and community activists fighting to release political prisoners and reappear “missing activists."

In the 1970s, President Luis Echeverría also focused in on investing in state infrastructure and public services and began to accumulate a high debt from borrowing money. President Lopez Portillo continued to borrow money to fund these initiatives as well. In 1982, Miguel de la Madrid, a Harvard trained economist, came into the presidency intending to lower the debt as much as possible.

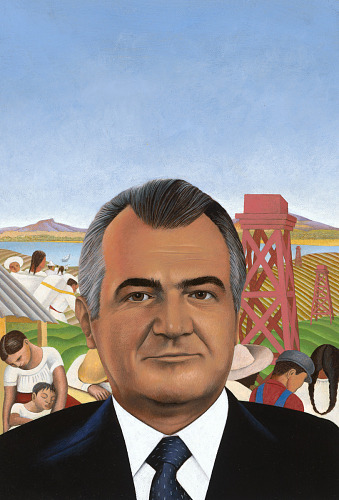

Time Magazine's December 1982 issue featured President de la Madrid on their front page in the piece titled, "Mexico Crisis: we are in an emergency,” referencing the 1982 debt crisis where Mexico's foreign debt grew to $80-$85 billion. Behind de la Madrid are working peasants on rural land, including water towers. De la Madrid seems proud of the background, giving a half-smile in the painting. The magazine paints de la Madrid as the defender of the marginalized in the economic turmoil. According to Time Magazine writer George Russel, “De la Madrid has also made clear that he will do as much as possible to protect government programs that aid the peasantry, the poorest element of Mexican society.” Unfortunately, de la Madrid’s pledge did not ring true. Encouraged by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, he reduced government spending and cut down large public funding and investment to lower the debt. These initiatives included the decentralization of public services like healthcare, focusing on working towards privatization. These efforts specifically hurt the peasantry and working class by lowering the quality of the services. When one looks back to the Time Magazine painting knowing de la Madrid’s actions, it seems the emergency de la Madrid referred to is how the working class and rural people benefit from these services. Rather than serving as their defender, de la Madrid acted as their oppressor and continued the trend of PRI oppresison. De la Madrid's administration also made it clear that it wanted little to no help from other countries in the economic recovery process.

"The miracle must be made by Mexicans themselves. If the U.S. can learn anything from the tribulations of its neighbor, it is that Mexico has become a mature enough force in the world to decide how to face its own problems.”

Héctor Hernández, Secretary of Commerce under President de la Madrid

Mexico’s political administration set its sights on establishing a strong independent Mexico on the world stage. With the focus on the Mexican economy, President de la Madrid neglected to consider Mexico City's environment. Mexico City lies on top of an ancient rock bed that intensifies seismic waves, making it more susceptible to earthquakes. The 1957 earthquake shocked the country into passing legislation to improve the construction of buildings. The earthquake knocked down the Golden Angel of Independence, a figure that stood for Mexican independence from Spain while also representing international tourism. People were upset that the emblem of victory against Europeans and Mexican greatness had fallen. After the earthquake, the Mexican government passed new regulatory measures to ensure Mexico City buildings met the international building safety standards to reduce the damage of future earthquakes. In theory, this meant that buildings would not easily collapse. However, in response to the housing crisis in Mexico City caused by migration to the city and rent-control prices, the government did not follow the 1957 standard. In the 1960s-1970s, the government approved the construction of large multi-story apartment buildings and smaller apartments to lower housing costs in the housing shortage. These structures were built using poor construction materials and did not strictly comply with the 1957 standard. Facilities were out of date and overcrowded. Considering how President de la Madrid cut government spending, this meant that the buildings lacked adequate maintenance.

Handling of Earthquake

In his book Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico, journalist Juan Villoro explains that President de la Madrid did not address the effects of the earthquake until citizens forced him to. Villoro states, "the president acted in a way consistent with a long tradition in the governments that defined the twentieth century in Mexico. He decided that the best way to fight a tragedy is to deny its existence." De la Madrid believed he could maintain the image of an independent Mexico he tried to create by downplaying the earthquake. He continued to use historic PRI rhetoric regarding disasters. Like President Luis Echeverría when he denied his involvement in the Tlatelolco massacre, de la Madrid used similar rhetoric in describing the earthquake as an unforeseeable event that Mexicans will overcome. Given the legacy and lessons of the 1957 earthquake, it became clear to the people that the lack of government supervision in Mexico City buildings contributed to the disaster’s impact.

"My family was not killed by the earthquake; what killed them was the fraud and corruption fostered by the government of Mexico."

Survivor of earthquake, "Nothing, Nobody: The Voices Of the Mexico City."

While earthquakes cannot be prevented and cause damage to people's lives, this earthquake exposed the government's corrupt foundation and the oppression of the marginalized. In the collapsed federal district attorney general headquarters, the bodies of prisoners who “disappeared” were found in the rubble. Human rights activists began to question why. Working-class people and the peasantry were also hit the hardest because of the government's poor maintenance in underfunded buildings. Some city officials allowed landlords to get away with violations for a fee. People could no longer escape the government repression in their own homes because the government, the same force that swore to protect them, neglected them. Mexico's corrupt administration laid exposed to all its people but not to other countries. In an attempt to save the image of the government to the world as a powerful and independent country, de la Madrid intially rejected foreign aid intervention.

“We are prepared to deal with this situation, and we do not have to turn to external aid. Mexico has sufficient resources, and, together, people and government, we shall move forward. We are thankful for good intentions, but we are self-sufficient.”

President Miguel del la Madrid

The Mexican government attempted to establish a sense of normalcy as a form of control to move on from the earthquake. President de la Madrid faced criticism from citizens, including other countries for his rejection of help. While he eventually allowed help from different countries, de la Madrid did not hold back in expressing his public opinion on getting help from different countries. On September 24, 1985, he said the earthquake would “complicate the management of Mexico’s foreign debt.” De la Madrid, despite knowing citizens needed help, did not want to help because he prioritized the economy. Citizens knew that they could not trust the government and decided to take matters into their own hands.

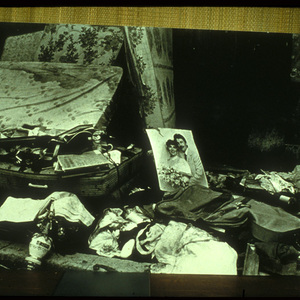

In a photo of rubble from the earthquake, a poster of la Virgen de Guadalupe, a symbol of purity in Catholicism (a religion practiced by the majority), laid in ruins. The photo captures how government corruption spilled over the private lives of people. People began to see government corruption right in their own homes instead of solely in the disappearance of political activists. Their home included their loved ones, shelter, and basic needs. Now, thousands of people did not have shelter or water for days, with some living on the streets for weeks. More than one million people did not have access to water. Mexico City's work-life, concentrated in the central city area (where most of the damage took place), was also severely disrupted by the earthquake. Urban development in Mexico typically occurred in this part of the city as many viable institutions and services took place historically there, encouraging people to settle in the center. However, the government's mishandling of the situation stripped their lives bare. Similar to the 1957 Golden Angel destruction, the photo of La Virgen depicted a symbolic collapse of the Mexican people and their identity. Now, people sought out ways to reconstruct the past while figuring ways to prevent the long historical PRI corruption from tainting it yet again.

Taking Matters into Own Hands

In the upcoming weeks of the earthquake, people formed organizations like the Coordinadora Unica de Damnificado (CUD) dedicated to rebuilding the city. Leslie Serna, a member of CUD, revealed that the army cut off the Historic Center. President de la Madrid claimed he sent the army to help rescue efforts, but many eyewitnesses claimed otherwise. The Mexican army, a historic symbol of the government, did not allow people to help rescue efforts. Serna, however, explained that people broke down the cordones established by the army and made street encampments.

“We didn’t have much of an idea of what to do, and we didn’t have any great plan; we did one thing at a time, and things had their own dynamic. Suddenly we were an organization and we had named commissions and a board of director."

Leslie Serna, "After the Earthquake: Victim Coordinating Council."

The CUD was disorganized and messy, like the government, at first. It first controlled the situation by creating makeshift places where people had shelter after their houses collapsed. However, unlike the government, the organization actually desired to help people. CUD gained major support from people and eventually operated similar to a traditional government with its delegation of powers and responsibilities. These responsibilities shifted from providing shelter to much more.

“We would ask for expropriation of the lands, neighborhoods, and buildings affected by the earthquake; the secondpoint was the restoration of public services in some of the affected zones; and finally, we would outline a popular program of reconstruction."

Paco Saucedo, "After the Earthquake: Victim Coordinating Council."

Serna's intial claim that CUD did not have a real plan when it first started changed immeditely in just a few weeks. Paco Saucedo shows the shift from providing shelter to creating a list of demands for the president to approve in October. Instead of government officials drafting up these policies to help citizens, the people did it themselves. In doing so, they took into consideration the voices of the working class, the peasantry, and their own needs. CUD members did not pay attention to what the government needed from them, but rather what they needed from the government. Women also found their voice within this movement. Dolores Padierna, the founder of the Union of Residents of Central Colonial, helped build encampments on the streets and fought to stop the eviction of refugees in churches. The union fought to receive water and services by the government. Instead of the government taking care of its citizens, people took care of each other by providing basic necessities.

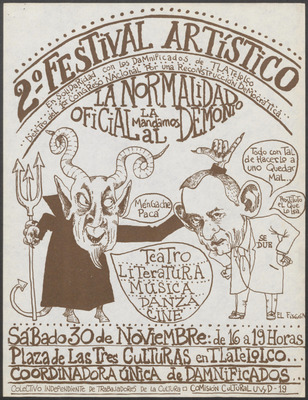

Posters demonstrate how the CUD and other organizations organized by condemning the government through leisure activities. The piece “2nd Festival Artistica,'' by the Coordinadora Unica de Damnificados depicts the devil in the process of grabbing President de la Madrid's head. De la Madrid is not looking right into the viewer like the Time Magazine cover and no longer looks like a strong president. Instead, the piece mocks de la Madrid by depicting him looking weak by having him look down to avoid staring at the devil. In between the two figures is a text stating, “the government official narrative of normalcy we send to hell.” By displaying the devil taking de la Madrid to hell, the CUD condemned the actions of government officials. The ad also called people to meet at the Plaza de Las Tres Culturas on November 30 from four to seven p.m., for theatre, literature, and other activities. By having these activities, families could bring their children and loved ones to enjoy them while supporting efforts criticizing the lack of government rescue measures. Government corruption and inadequacy seeped into the lives of Mexican family. The CUD created a space where people shared their grievances through artistic and thought-provoking ways against the government.

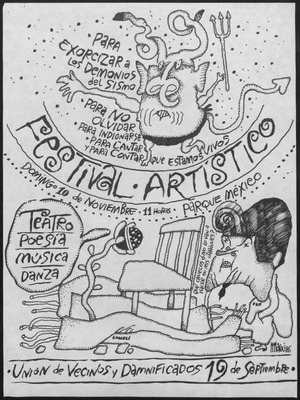

People continued to talk about the earthquake even after time passed. In the “Festival Artistico" poster dated 1987, the flyer invites people to an event on November 10, 1987, using the recurring theme of a devil caricature. The poster claims the festival will exorcise the devils (government officials) responsible for the lack of earthquake efforts. The festival will accomplish this task through activities including singing and poetry. The poster specifically emphasizes that people will talk and sing to show that they are still alive despite the lack of help by the government, implying that the government tried to kill them by not providing them relief. This bold statement was published, showing how public activities challenged the government. Victims organized efforts to bring the earthquake into light even though two years had passed. They refused to let their voices get silenced like the Student Movement of 1968 was.

CUD and other organizations laid the foundation for activists to follow, awakening people to the capability of their actions. The historic neglect of Mexico City buildings, slow rescue efforts, and rejection of foreign and citizen help were only a few ways the government failed. Despite these challenges, the Mexican people operated as a government by protecting and providing services to one another in the name of mutual solidarity. President de la Madrid's reckless actions vitalized the Mexican spirit, who began to realize their true potential by engaging in mutual aid efforts. Mexican political attitudes towards national elections drastically changed considering how some people lost faith in PRI's legitimacy in the 1970s and stopped voting.

However, the 1985 earthquake pushed the urban poor, the working class, and the peasantry into getting involved in politics to stop PRI. The earthquake incited action among Mexicans that eventually expanded to the election polls in the 1988 national election, where the two main candidates, PRI Carlos Salinas de Gortari and Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, ran against each other. Some took direct action and wrote to presidential candidates. In anonymous letters to Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the poor and marginalized wrote directly to him. In one excerpt, a man describes Cardenas as the hope for "all the poor" against "diabolical functionaries." The man's lack of punctuation and poor spelling illustrates how, despite educational barriers that divide citizens, people realized the power they carried. When people unite together with the sole interest of helping one another, real change can occur.

Bibliography

"2º Festival Artístico.”Archivo Digital de Efímera de América Latina y El Caribe.” Princeton University. The Trustees of Princeton University, 1987.

“After the Earthquake: Victim Coordinating Council." In The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics, 579–590. Duke University Press, 1985.

"Among the rubble, a wedding photograph stands out," 1985. Galeria de la Raza.

"Festival Artístico.” Archivo Digital de Efímera de América Latina y El Caribe. Princeton University. The Trustees of Princeton University, 1987.

"Letters to Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas." In The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics, 591–597. Duke University Press, 1985.

Mantel, Richard. “Miguel De La Madrid Hurtado.” Painting of Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado, 1982. National Portrait Gallery.

Nadelman, Rachel, Caroline Nichols, Sara Rowbottom, and Sarah Cooper. “Learning from the Mexico City Earthquake: Dynamics of Vulnerability and Preparedness- the Case of Housing.” Enhancing Urban Safety and Security Global Report on Human Settlements, 2007.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), ed. “Earthquake Mexico 1985.” PAHO Archive, December 22, 2008.

"A pile of rubble contains a piece of furniture with a poster of La Virgen de Guadalupe," 1985. Galeria de la Raza.

Poniatowska, Elena, Arthur Schmidt, and Schmidt Aurora Camacho de. Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Mexico City Earthquake. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995.

Randall, Laura. Changing Structure of Mexico: Political, Social, and Economic Prospects. London: Routledge, 2015.

Russell, George. “Mexico: We Are in an Emergency.” Time. Time Inc., December 20, 1982.

Trevizo, Dolores. “Political Repression and the Struggles for Human Rights in Mexico: 1968–1990s.”2014.

Vale, Lawrence. The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Villoro, Juan, Mac Adam Alfred J., and Juan Villoro. Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico. New York: Pantheon Books, 2021.

"Violent Quake Hits Mexico 1957." The World's Finest News and Entertainment Video Film Archive. Mexico, 1957.