Art, Revolution, and the State

Much can be learned about any movement in history from the art it inspired; the consistent themes of humility, anti-colonialism, and class consciousness found in Mexican revolutionary art tell us about the role of the working class and indigenous culture in the revolution. Vanguards of muralism in the Mexican revolution like Rivera and Orozco centered the working class and indigenous experience in their art; some claim this was a way to turn state-sponsored murals into a vehicle for raising class consciousness among the Mexican people.

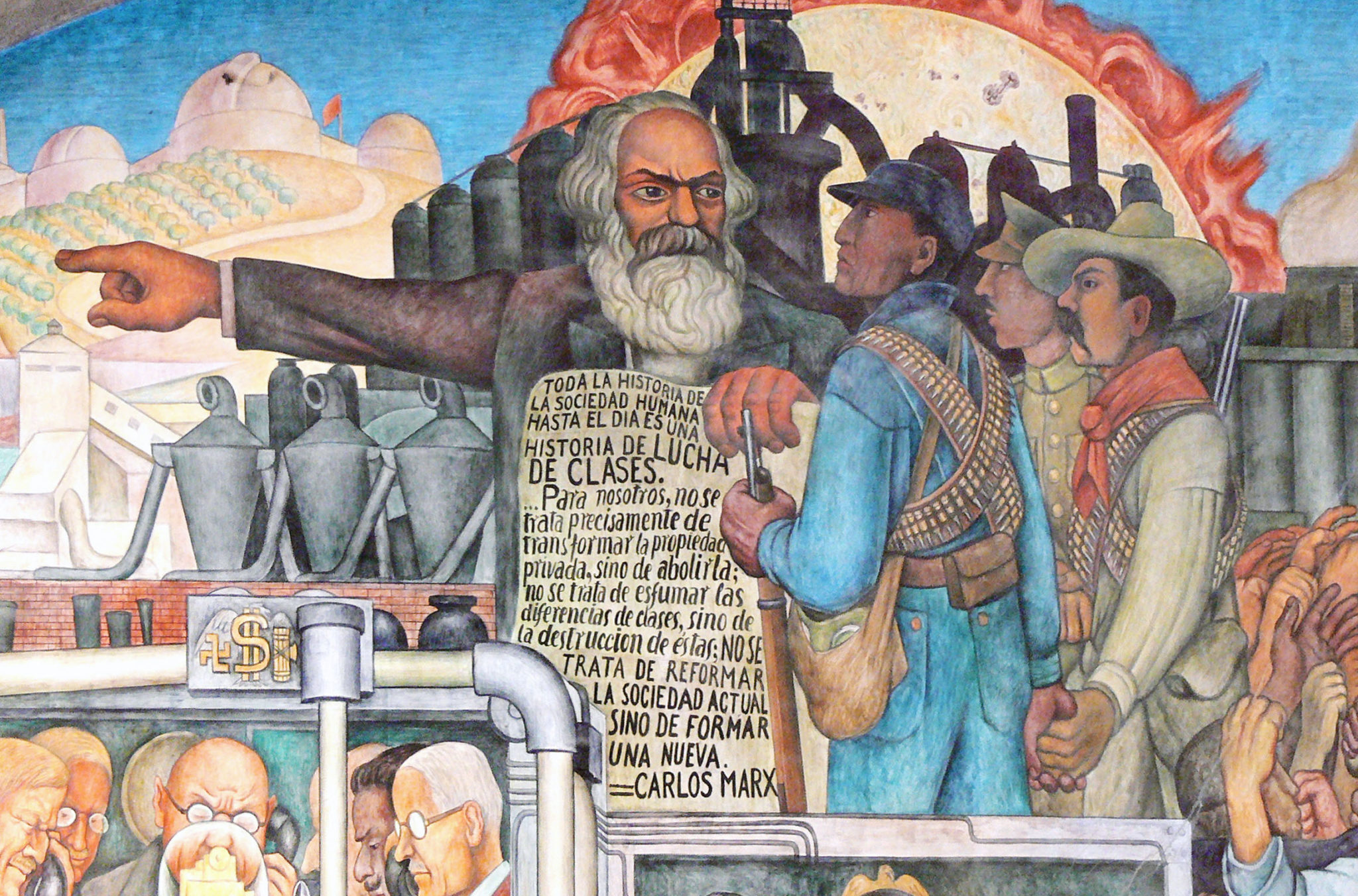

Rivera's murals carried very clear message: the ideas of Marx would emancipate the Mexican working class from the legacies of colonialism and the chains of capitalism. Mexico Today and Tomorrow, one of Rivera's celebrations of Marx, presents him as a leader among the Mexican working class. Holding a scroll with lines from the Communist Manifesto, Marx is pictured pointing indigenous workers and soldiers towards what seems to be a new, better Mexico.

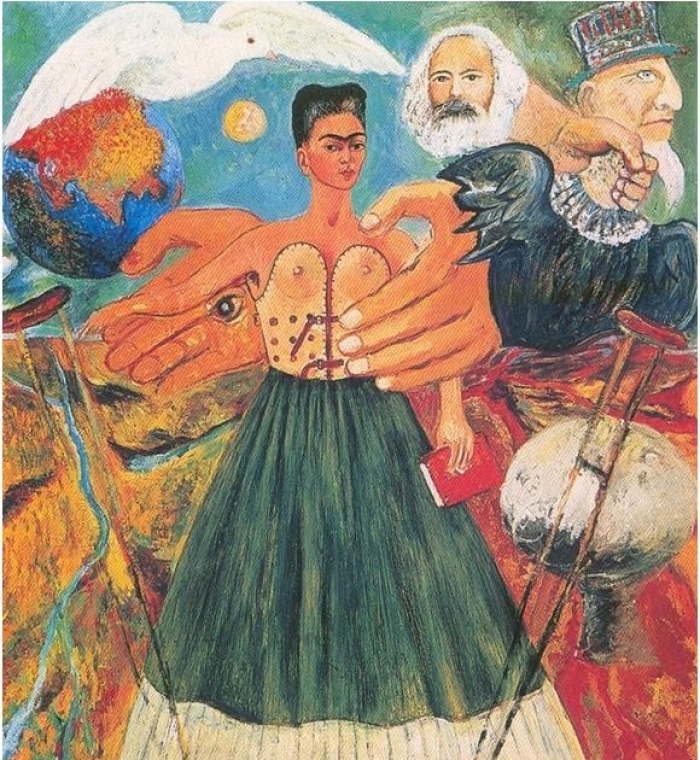

Similarly, Kahlo's portrayal of Marx stays loyal to the idea that Communism will liberate the working class. As Henderson explains, in Marxism Will Heal the Sick Frida's orthopedic leather corset embodies the suffering of the masses under the oppression of US capitalist forces. As the artist portrays herself as gently embraced by the reassuring, god-like hands of Marx however, she is reflected as able to throw away her crutches, promoting an evangelic-like message regarding the healing properties of Marxism for society.

Revolutionary Art and the State

The leaders of muralism were undoubtedly outspoken about their commitment to anti-capitalism and the Revolution. Yet, it is important to note that much of this art came about in the context of post-revolutionary Mexico-- when the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) alluded to radical ideas of the revolution to garner public support and consolidate its power. Consequently, because the state often replaced real structural change with these performative statements, the line between praxis and indirectly protecting the status quo became increasingly blurred for Revolutionary artists like Orozco, Kahlo, and Rivera.

Many would argue part of Jose Clemente Orozco's career exemplifies this disconnect. Pictured on the left is the panel Anglo-America, part of The Epic of American Civilization which decorates the walls of one of the libraries at Dartmouth College. The panel shows the prominent figure of a tall, stern-faced schoolmarm, here an overbearing agent of control, typifies the culture. She is surrounded by strictly regimented, expressionless children. Behind them the adults arranged in rows at a New England town meeting present yet another example of cultural rigidity-- the work is certainly heavily critical of capitalism and Anglo-America. The mural certainly inspired much controversy for its critical nature and location; the president of Dartmouth College received many letters from angry members of the community. Interestingly enough, when discussing this controversy, Orozco praised American society for having the same values the panel suggested it lacked:

“The position Dartmouth was taking expressed one of the most highly prized of American virtues: freedom — of speech and thought, of conscience and the press — the freedoms of which the American people have always been justifiably proud.” —Jose Clemente Orozco

Muralism and Governmentalism

Critics challenge the perception of muralism as a proletarian art form due to its presence in environments often inaccessible to the working class or directly connected to the state-- Orozco's Epic is located at the elite, private Dartmouth College and Rivera's Mexico Today and Tomorrow on the walls of the Mexican National Palace. Historian Mary Kay Vaughan notes that his murals provided state with illustrations of the kind of populism that flowed heavily from politician's rethoric. Additionally, overdetermined by their placement in government buildings, mural art not only reflected a government ideology but helped provide one. The very presence of soldiers (pictured on the right) on the mural reflects the abandonment of the Zapata and Marxist view of the state as a tool for class oppression and supports the perception of muralism as a vehicle for populism and the consolidation of state power.

In Muralism and the People: Culture, Popular Citizenship, and Government in Post-Revolutionary Mexico, Coffey signals to Foucault's concept of governmentality, which accurately describes the relationship between muralism and the post-revolutionary Mexican state. Foucault traced the historical shift from autarchy to te modern state, arguing that the weakening of the divine rule occasioned the rise of doctrines on how to rule. Rather than seeking to legitimately rule, modern forms of social and political organization are concerned with how to rule. Governmentality manifests itself in the instrumentalization of culture for social development in post-revolutionary Mexico as well as in the muralists desire to socialize artistic expression. Muralism, then, could be interpreted as a vehicle for said instrumentalization of culture; the movement helped sustain the narrative that the goals of the revolution could be accomplished through the emerging state.

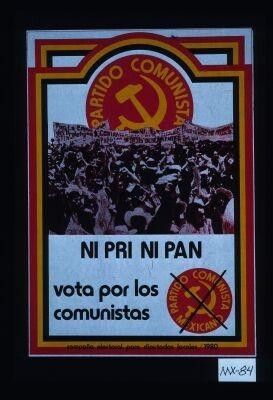

Ni PRI ni PAN, Vota Por los Comunistas

A number of factors, including the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico, caused the PRI to lose its absolute majority in both chambers of the federal congress for the first time in 1997. After several decades in power the PRI had become a symbol of corruption and electoral fraud. Perhaps as a sign of loyalty to the Communist ideology and to Marx and Zapata's condemnation of the state, the pursuit of Revolution and the emancipation of the working class in Mexico continued. The poster featured on the right illustrates the left’s efforts to reorganize and consolidate its support base. As for muralism—regardless of its role in the PRI’s consolidation of power in the revolutionary period— it was able to immortalize many of the values that propelled the revolution forward.

Bibliography:

Mary Katherine Coffey, Muralism and the People: Culture, Popular Citizenship, and Government in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

Orozco, J. C. (2001). An Autobiography p. 158

Jackson, Allison (July 1, 2012). "Mexico elections: Voters could return Institutional Revolutionary Party to power" Global Post

Henderson, PL. “'Marxism Will Heal the Sick': Frida Kahlo and Karl Marx.” Culture Matters, https://www.culturematters.org.uk/index.php/arts/visual-art/item/2739-marxism-will-heal-the-sick-frida-kahlo-and-karl-marx

David Alfaro Siqueiros, "Art and Corruption"

“Emiliano Zapata, a Revolutionary Icon for Mexico and the United States”

- Luis Santiago Vargas, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México

Sonia Hernandez, “Caritina M. Piña and Anarcho-syndicalism Labor Activism in the

Greater Mexican Borderlands, 1910–1930” Chapter Eight of Writing Revolution (2020)