Luis Donaldo Colosio’s March 6, 1994 Speech in Mexico’s Changing Political Landscape

This is a digital exhibit curated by Ignacio Gutierrez, Dartmouth College Class of 2025.

“Perfect dictatorship” is what Nobel Prize-winning writer Mario Vargas Llosa dubbed the political party Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) that controlled the Mexican presidency for seventy-one consecutive years. The intellectual rightly criticized the monopoly of power and the democratic facade of the hegemonic political machine. Mexico’s history with the PRI is an elaborate saga. Luis Donaldo Colosio’s campaign for the Mexican presidency in 1994 under the party is a vital episode worth examining in greater depth. On March 6, 1994, Colosio gave his most influential speech in front of the Monumento a la Revolución. His address was significant, for he presented himself to the Mexican electorate as a PRI leader with a new set of ideals. Social and political events made Mexican society doubt the legitimacy of the political party. However, by admitting that his party needed reform, committing to democracy, and welcoming political pluralism, Colosio sympathized with an anguished Mexican society that repudiated the PRI.

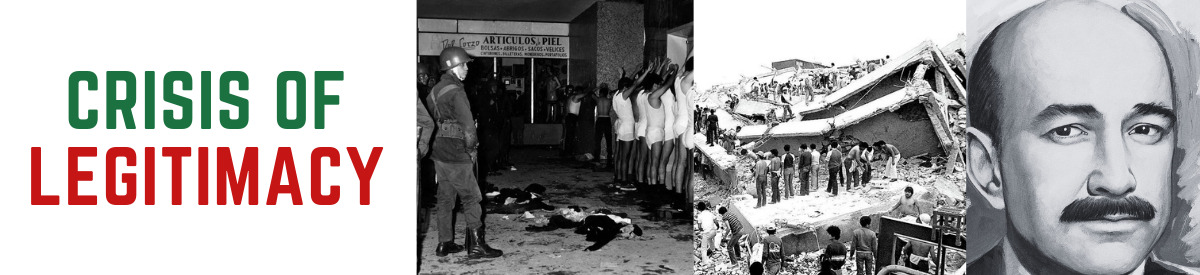

The Tlatelolco Massacre, 1976 financial crisis, the incompetent government response to the 1985 earthquake, and electoral fraud in the elections of 1988 made an agonized Mexican society question the legitimacy of the PRI. On October 2, 1968, prior to Mexico’s Summer Olympics, police officers and military troops shot into a crowd of unarmed students. Thousands of demonstrators fled in panic as tanks bulldozed over Tlatelolco Plaza—approximately forty students were killed and four thousand injured. The country fearfully witnessed as the Mexican government used repression and violence that recognized no limits against peaceful protesters. In 1976, Mexico experienced one of its most severe financial crises. After twenty years of relative stability, the Mexican peso suffered a 60% devaluation of its currency. Ordinary citizens paid the price for the economic recession. Many lost their jobs, houses, and most notably, faith in the PRI. On September 9, 1985, a devastating earthquake hit Mexico City. Neighborhoods crumbled, and thousands died, yet the government was indifferent to the devastation. The feeble response of the PRI sparked a grassroots movement that challenged the corruption of the government and its inability to provide aid services. In response to the PRI’s failures, fed-up activists and politicians created the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), which sought to topple the dominant political party in the 1988 elections with candidate Cuauhtemoc Cardenas. On election night, it appeared as though Cardenas would defeat PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari. However, a system malfunction caused the voting apparatus to shut down. After it restarted, Salinas, who had lagged Cardenas, was mysteriously ahead in the electoral count. Large sectors of society characterized Salinas’s victory as electoral fraud. By the 1994 presidential election, the Mexican populace had awakened to the authoritarian nature of PRI. The dominance of the political party began to fade.

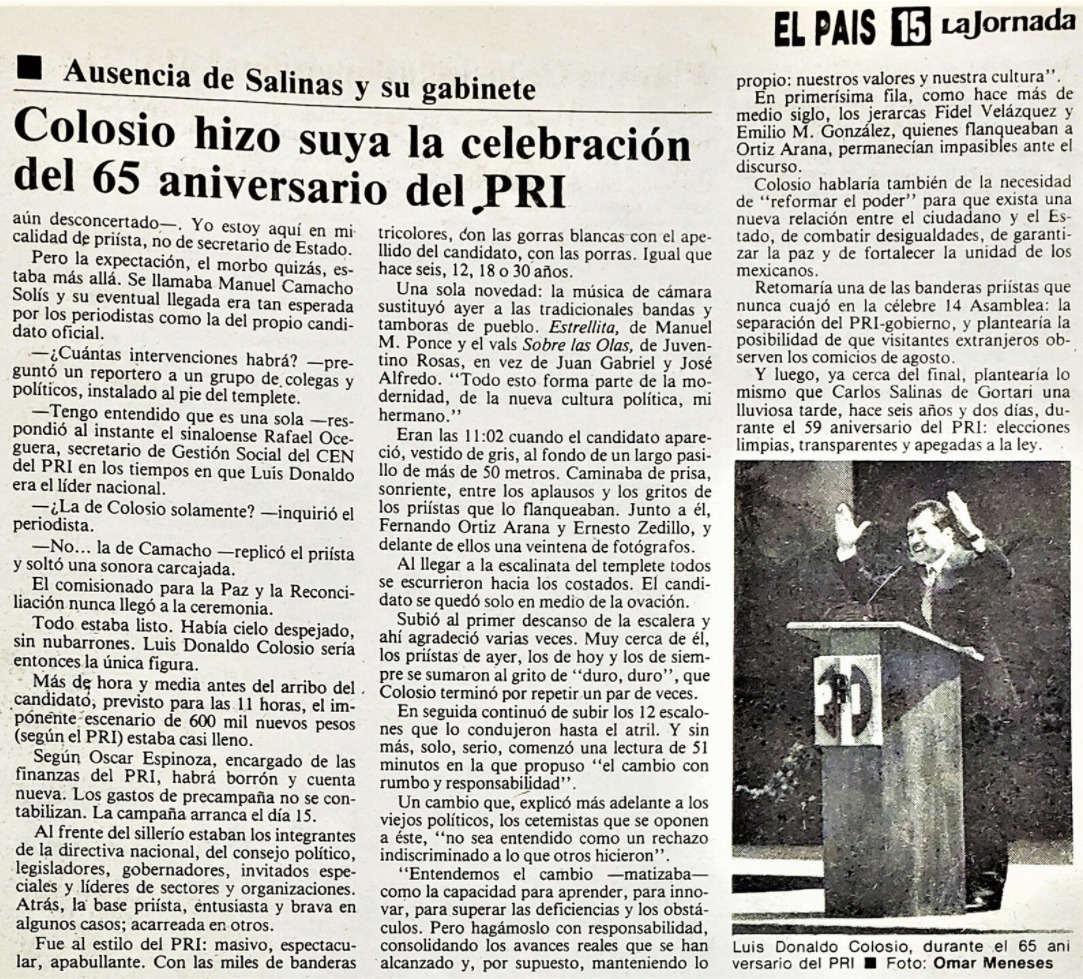

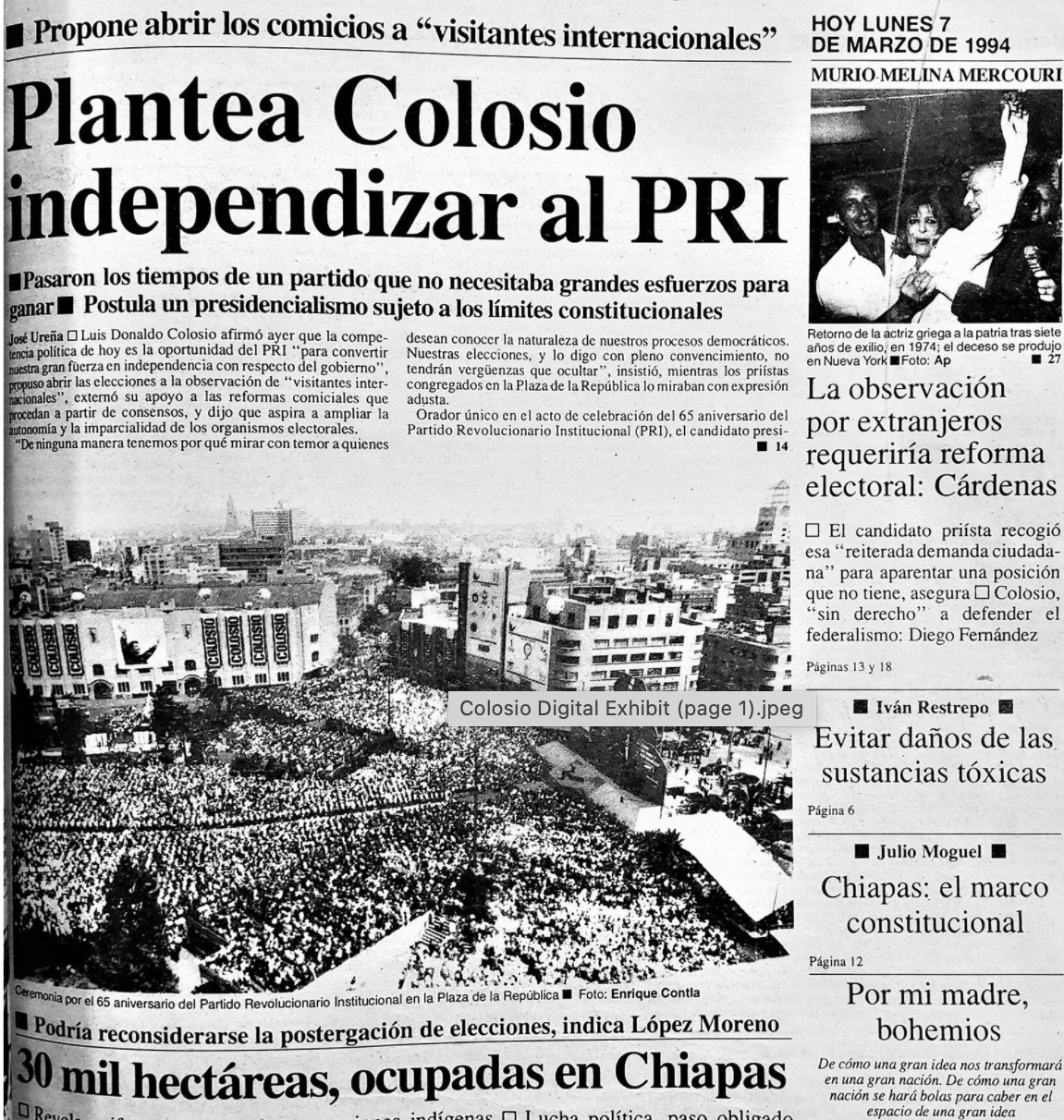

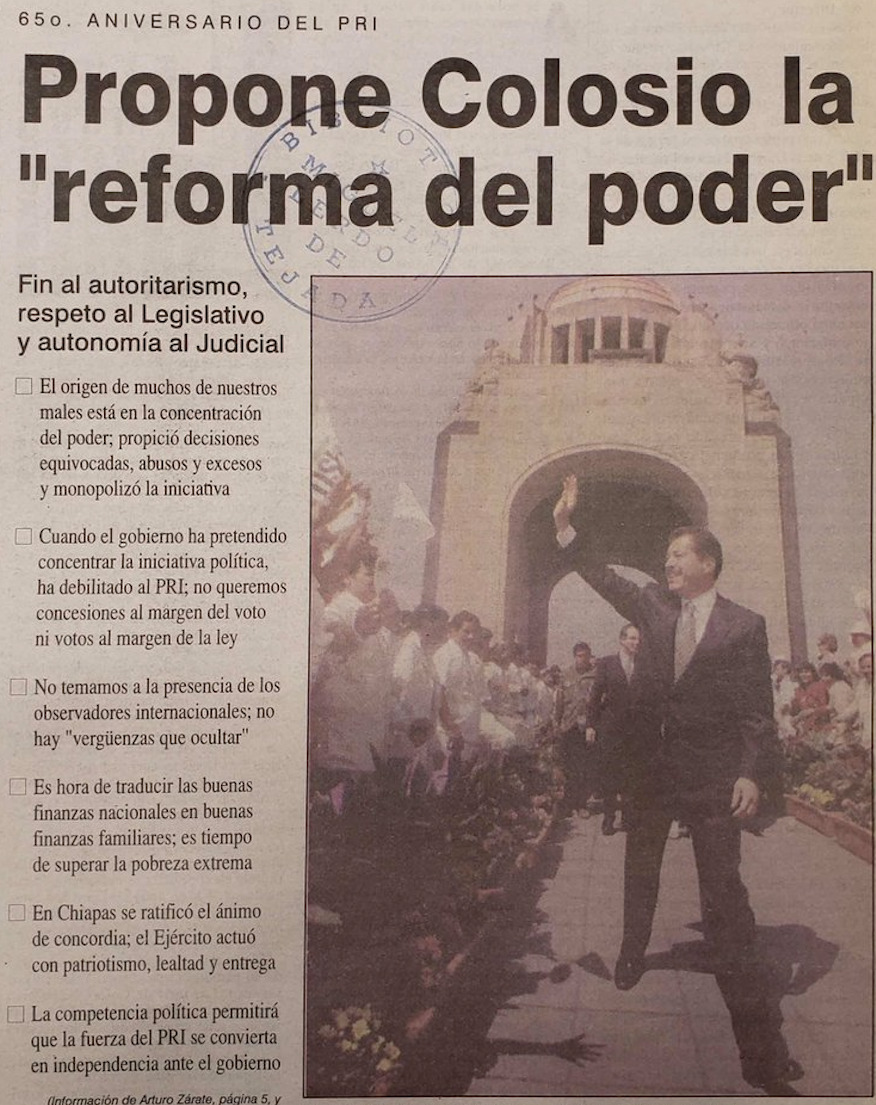

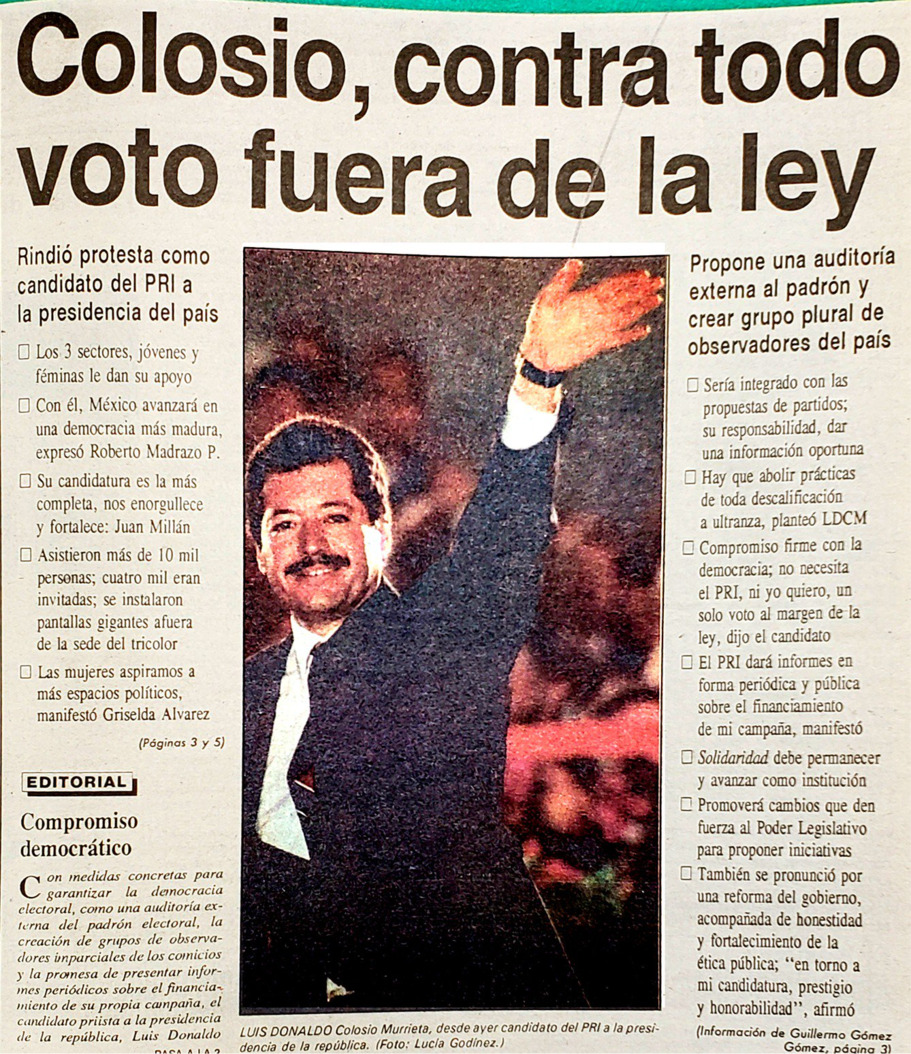

In his speech, Colosio presented a new PRI that sought to win back the trust of those who had lost faith in the party. Many viewed the candidate’s address as his formal break from the party. For example, a day after the speech, the Jornada newspaper published the headline that Colosio had stolen the show on the party’s sixty-fifth anniversary. At the end of the front page, it emphasized how Colosio repeatedly mentioned the need for change—a phrase that comes up fifty-nine times during his speech—which angered old PRI politicians who saw the political candidate challenging the party’s hegemony. In addition, the newspaper also documents in bold the absence of president Salinas and his cabinet members, further speculating the existence of separation between the PRI and Colosio. Another editorial spotlighted Colosio’s attempt to become independent from PRI, underscoring the political candidate’s desire to alter the nature of his party. Indeed, in his speech, Colosio asked for his party’s reform. He paints the image of a downcast Mexico, one that has not benefited from the rule of previous PRI administrations.

“I see a Mexico that is hungry and thirsty for justice. A Mexico of aggrieved individuals, of individuals aggrieved by the distortions of the law by those who should serve it. Of women and men afflicted by the abuse of the authorities and the arrogance of government offices.”

Luis Donaldo Colosio

Colosio sees “aggrieved” and “afflicted” individuals. His use of words is significant because he implicitly criticizes the PRI for causing such harm. Although Colosio does not mention the political party, he alludes to a despondent civil society. He condemns the “authorities,” “government offices,” and the ruling party that had been in power since 1930 that allowed such a state: the PRI. He was one of the few politicians who understood that his party needed to adapt and re-structure in reponse to the social unrest of the Mexican populace. The phrase is commendable, for it is rare that a political candidate recognizes the political deficiencies of his own party—something that allowed Colosio to portray his candidacy as distinct from the PRI.

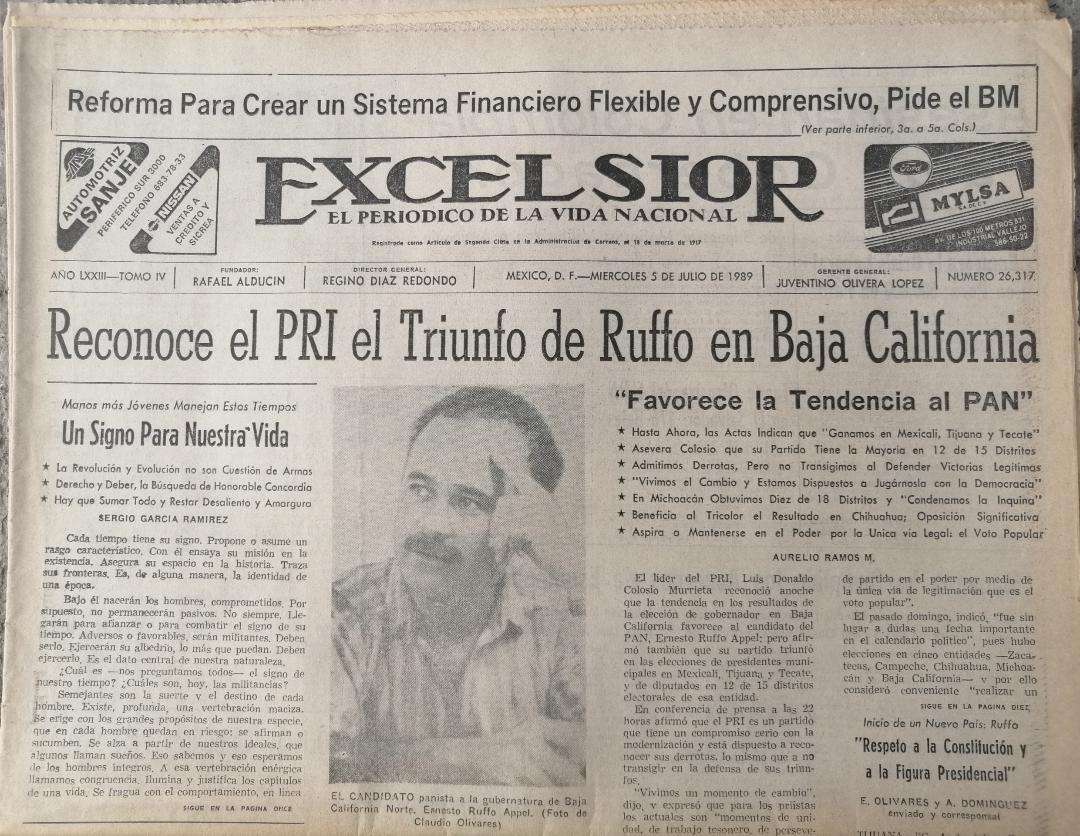

Colosio’s commitment to a democratized power allowed him to sympathize with a nation that viewed the PRI as authoritarian. The year was 1989, and the winds had changed for Mexico’s dominant political party. Ernesto Ruffo Appel, candidate for Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), won Baja California’s governorship and sought to become the first Mexican governor not affiliated with the PRI. However, the PRI political machine—capable of electoral fraud—stood in the way. Interestingly, when Appel was declared victorious, the newspaper Excelsior highlighted the PRI’s concession, not the candidate’s electoral victory. The editorial wrote of Colosio, who at the time was president of the PRI and oversaw the party’s electoral races, and of how he had spoken about the importance of adhering to democratic processes. Amidst the PRI’s defeat, Colosio faced two options: steal the election like Salinas in 1988 or become the first president of the PRI to admit defeat. In a political move that angered many PRIstas, Colosio pronounced that phrase never heard before in the PRI’s hegemonic history: “the electoral trend does not favor us.” Traitor Colosio! was the cry that arose from the PRI members who refused to accept the political result. By not interfering with the political processes of the 1989 Baja California elections despite internal party pressure, Colosio demonstrated his commitment to respect the integrity of Mexican democracy—a theme he would carry in his 1994 electoral campaign.

“[The PRI’s] heritage must be a source of demand, not complacency or immobility. Only authoritarian parties claim to base their legitimacy on their heritage. Democratic parties win it daily.”

Luis Donaldo Colosio

Colosio addressed the PRI’s legitimacy and stressed that, like in democracies, it must be earned and not just tolerated like in authoritarian states. Once again, Colosio tacitly critiques his party and mentions that it has become “complacent” and “immobile” due to its concentration of power. He sought to dismantle the growing aura of the PRI as an authoritarian party, as a perfect dictatorship where incumbent presidents appointed their successors and rigged elections. The political candidate also alludes to the Mexican Revolution when he mentions his party’s heritage. He recognized that his party no longer shared its founding values and sought to live up to the revolution’s democratic promise, not just historically but “daily.” The newspaper El Nacional praised Colosio’s commitment to democracy. Like Colosio, the newspaper highlighted Mexico’s need for democratic transformation. A transformation inhibited in Mexico. A demand that the past PRIstas had failed to bring forth. Colosio was at the forefront of the democratic progress in Mexico, responding to a Mexican society that demanded it.

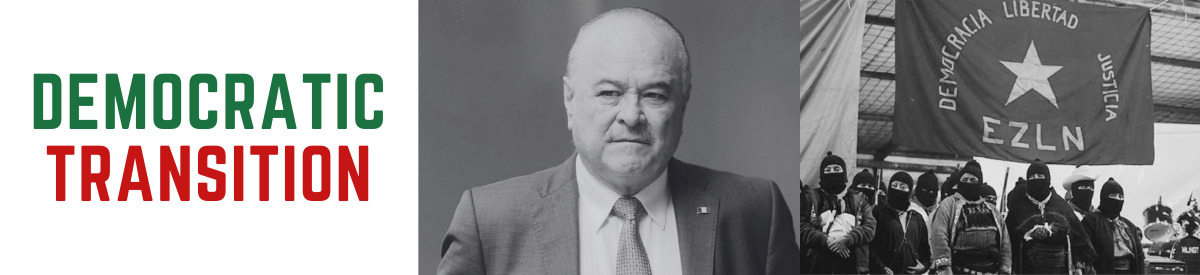

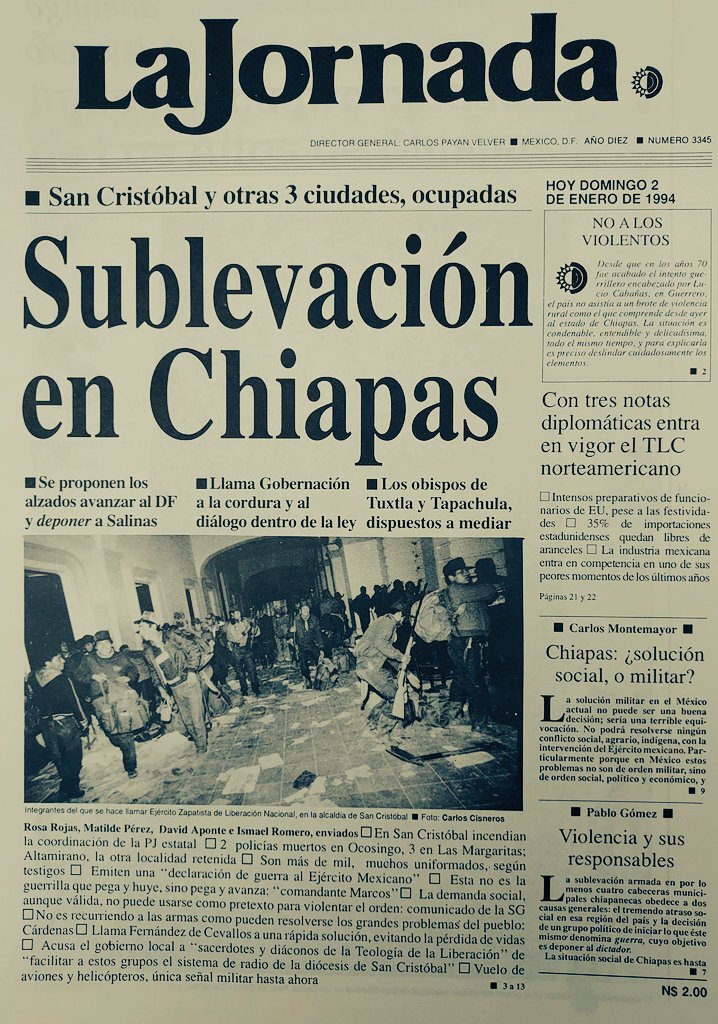

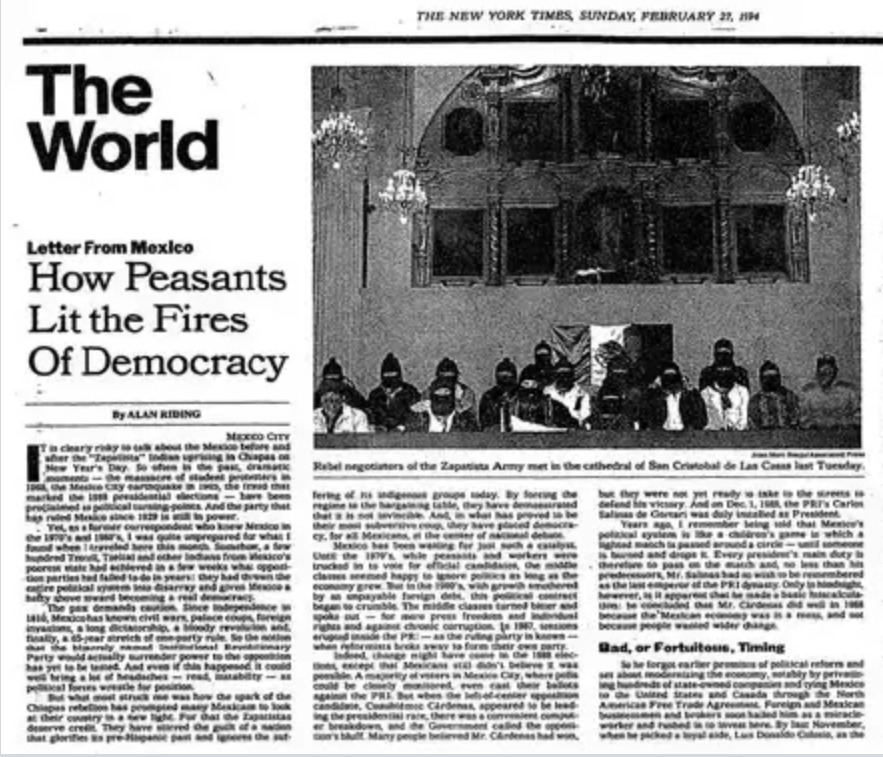

Another political force that advocated for Mexico to transition to democracy in 1994 was the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). The EZLN is a military-political organization formed primarily of indigenous people from the Mexican state of Chiapas that took up arms against the government on New Year's Eve in 1993. On their First and Second Declarations of the Lacandon Jungle, the movement harshly condemned the monopolized one-party system of the PRI and sitting president Carlos Salinas de Gortari for blocking democracy, impeding liberty, and having justice that exists for the corrupt and powerful. One of the fascinating aspects of the Chiapas guerilla movement is its commitment to democratic reform praised by intellectuals like Noam Chomsky and editorials like the New York Times. The group advocated for democratic conditions that would ensure freedom for the working majority. The EZLN also never considered itself the vanguard of the popular movement, nor did it see its form of struggle as the only possible way to bring a democratic transition. And although the group took arms against the government, its commitment to open dialogue and political collaboration with civil society remained one of its key strengths.

After Colosio’s death, the EZLN commented:

“Colosio always referred to our movement with prudence and respect. His latest statements marked a clear commitment to compete on equal terms with other political forces. He recognized that the country was suffering from great injustices and was clearly distancing itself from the Salinista regime and its economic and social policies.”

Zapatista Army of National Liberation

The EZLN—although highly critical of the PRI and its sitting president—and Colosio shared mutual esteem. Once again, the political candidate diverged from his party in that he was willing to listen to the people of Chiapas’ demands. Whereas Salinas, akin to his authoritarian nature, sent military forces to put down the armed insurrection in its outbreak, Colosio expressed solidarity with the movement conveying the need for all voices to be heard—including those critical of his party. The political candidate was sensitive to the demands of the EZLN. Colosio had spearheaded the organization SOLIDARIDAD at the beginning of the 1990s that sought to support impoverished neighborhoods but recognized that existing social programs had done little to address the needs of the lower-class indigenous and working communities. Instead of dismissing the issue, the political candidate often referred to the struggle as a call for conscience. Colosio acknowledged that the PRI had failed to live up to the democratic demands of its citizens.

“Today we live in the competition, and to the competition, we must attend. To do so, old practices must be left behind: those of a PRI that only dialogued with itself and with the government, those of a party that did not have to make great efforts to win.”

Luis Donaldo Colosio

In contrast to the PRI's history with electoral irregularities, Colosio welcomes political pluralism amidst the competitive elections of 1994. Colosio comprehended that the PRI no longer had victories assured. Oppositional parties were slowly gaining traction as the Mexican electorate rejected the rule of the PRI. The political candidate sought to win the 1994 election lawfully with hard work and dedication, not electoral fraud. Once again, Colosio sees the political diversity in Mexican politics as an opportunity to sympathize with the nation, emphasizing that the “old practices” of the PRI must be left behind. In so doing, the political candidate sought to distance his candidacy from the hegemonic PRI that had inhibited party competition.

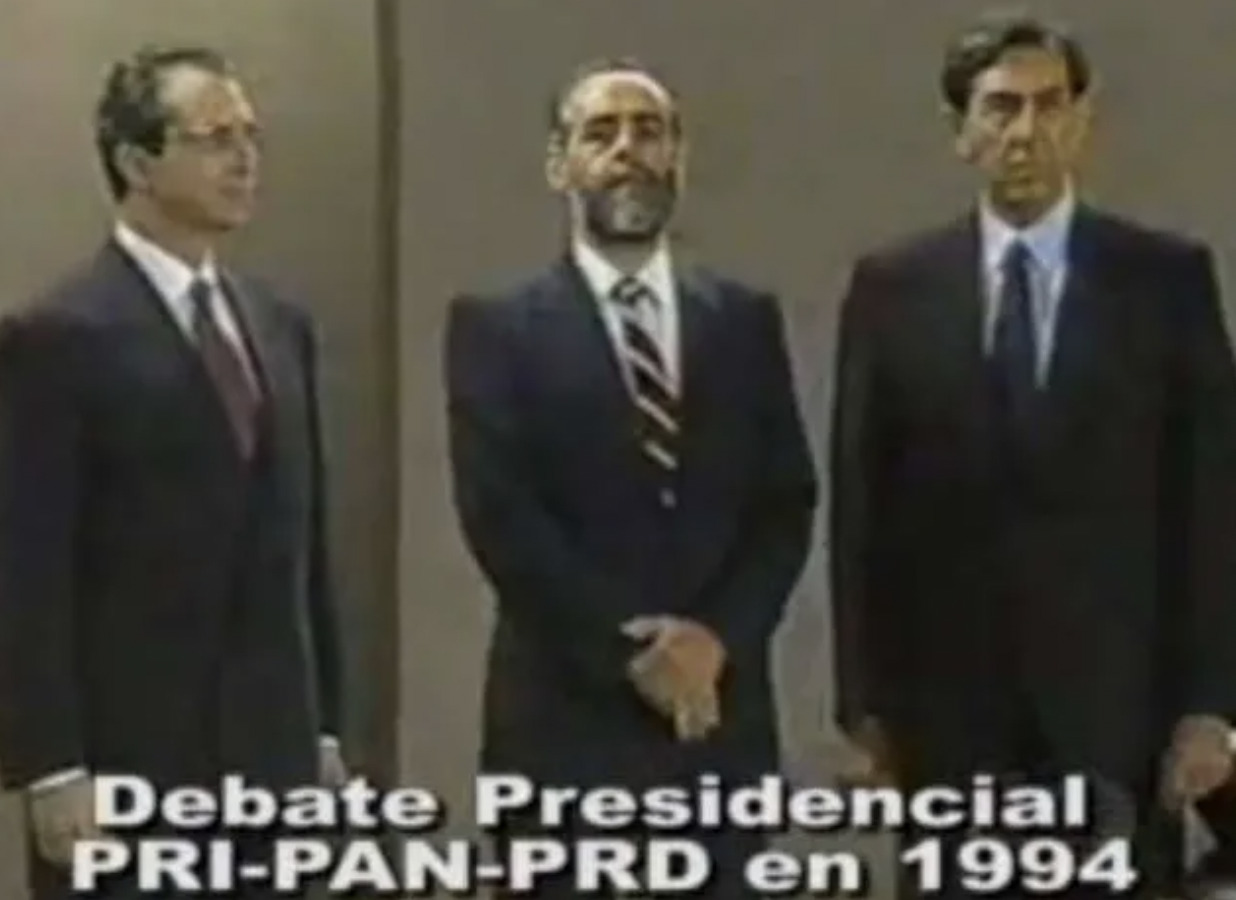

Mexico was arguably experiencing its first competitive elections in 1994. The three main candidates—Cuautemoch Cardenas for PRD, Diego Fernández de Cevallos for PAN, and Luis Donaldo Colosio for PRI—each had a chance to win the presidency. Cardenas was running with the newly formed PRD. The candidate had put up a fight against Salinas in 1988 and sought to appeal to the ignored lower classes of Mexico, carrying forth the legacy of his father, former Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas. Cevallos was running with PAN, a party that had demonstrated its capacity to compete with the PRI by winning elections in the chamber of deputies, senate, and state governorships. A testament to the competitive atmosphere of the 1994 election is that Mexico hosted its first presidential debate. Prior to his death, Colosio had advocated for the televised event, which is admirable given that he was willing to share the stage—one which the PRI had blocked entrance since 1929—with his opposition. Salinas’s irregular victory in 1988 mobilized Mexico’s civil society to be more involved in electoral processes. Notably, the Federoal Elecotoral Insitute (IFE) emerged as an independent organ separate from the government and has administered Mexican elections since 1990. The distrust in electoral processes motivated the political candidates of the 1994 election to sign the Pacto por la Paz, Democia, y Justicia, which called for electoral integrity. By signing the agreement and championing the debate, Colosio differed from his PRI predecessors, specifically Salinas, by committing to a just and competitive election—even if faced with defeat.

The political candidate sought a change in Mexican politics, one that would break from the stereotypes of his party. Yet, a final question remains: why was Colosio affiliated with the PRI? He frequently emphasized the transformation that Mexico needed. Had the PRI not been the source of Mexico’s iniquities? After all, the political party had been the ruling authority in the country since 1929. Colosio did not seek to dismantle the PRI political machine. He desired to implement democratic policies absent in his party’s national project. But could his national vision not be implemented via another party? Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, for example, criticized the PRI from the PRD, a political party that he had helped form, who—like Colosio—sought to make Mexico an authentic democracy. Was the political candidate still loyal to Salinas? Would Colosio be corrupted by power once in office and not follow through on his promise to reform the PRI?

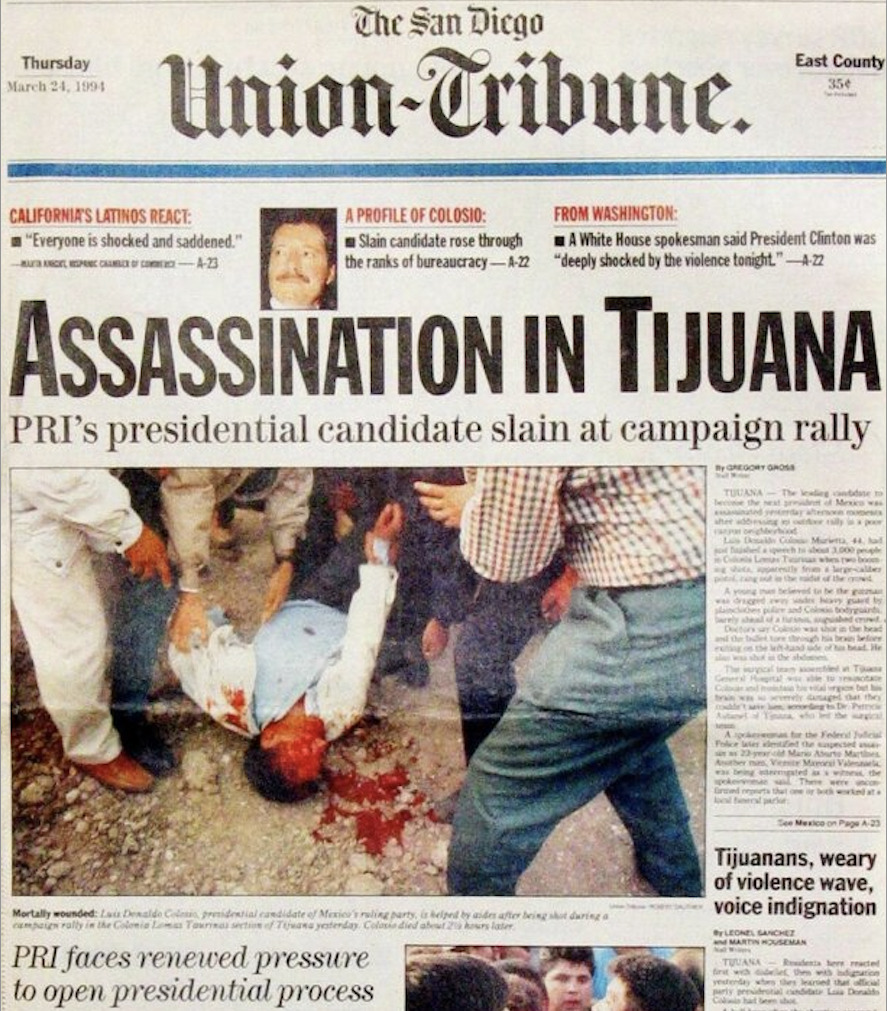

The barrel of a gun forever suffocated those questions. On March 23, 1994, two weeks after his speech, Luis Donaldo Colosio was assassinated in cold blood at a campaign rally. The country had to rest the vision the political candidate put forth. But even today, one cannot help but wonder if Mexico would have been different had Colosio become president in 1994.

The PRI would win the 1994 election with candidate Ernesto Zedillo, but it would lose its first presidential election in 2000 against PAN. The seventy-one-year hegemony of the PRI at the presidency came to an end.

Colosio may have lived a political contradiction by being a part of PRI. His efforts, however, are worthy of praise. Colosio dared to raise his voice against the PRI’s political machine with conviction and without fear. In his March 6, 1994 speech, the political candidate sought to revitalize the image of the PRI—a political party that in the eyes of the Mexican public had lost its legitimacy. In so doing, he appealed to a Mexican society that, along with him, demanded change. Perhaps that was Colosio’s only crime that cost him his life.

Primary Sources:

“After the Earthquake: Victim Coordinating Council." In The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics, 579–590. Duke University Press, 1985.

“After the Earthquake: Victim Coordinating Council." In The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics, 579–590. Duke University Press, 1985.

EZLN. “First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.” Radio Zapatista, 1994.

EZLN. “Second Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.” Radio Zapatista, 1994.

Youtube. (2011). Lic. Luis Donaldo Colosio Discurso Completo 6 de Marzo de 1994.

Secondary Sources:

Adler, David. “The Mexico City Earthquake, 30 Years on: Have Its Lessons Been Forgotten?” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, September 18, 2015.

Arreola, Federico. Así fue : la historia detrás de la bala que truncó el futuro de México. 1 ed. México, D.F: Alfaguara/Santillana, 2004.

Francisco, D., & Mendoza, D. (2019, January 3). EZLN, La Guerrilla Imaginativa. UNAM Global. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

Joseph, G. M., & Buchenau Jürgen. (2013). The “Perfect Dictatorship,” 1940–1968. In Mexico's once and future revolution: Social upheaval and the challenge of rule since the late nineteenth century (pp. 141–166). essay, Duke University Press.

Joseph, G. M., & Buchenau Jürgen. (2013). The Embers of Revolution, 1968–2000. In Mexico's once and future revolution: Social upheaval and the challenge of rule since the late nineteenth century (pp. 167–196). essay, Duke University Press.

Krauze, E. (2020, April 11). La Tragedia de Colosio. Enrique Krauze. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

Marini, Anna Marta. “El México que no fue: The Tentative Retelling of Luis Donaldo Colosio’s Assassination”. Comparative Cinema, [online], 2021, Vol. 9, Num. 16, pp. 31-51.

“Mexico's 1968 Massacre: What Really Happened?” NPR. NPR, December 1, 2008.

Molinar, Juan, and Jeffrey Weldon. “Elecciones de 1988 En México: Crisis Del Autoritarismo.” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 52, no. 4 (1990): 229–62.

Navarro, Carlos. “ Ruling Party (P.r.i) Nominates Social Development Secretary Luis Donaldo Colosio As 1994 Presidential Candidate.” University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository. University of New Mexico, December 1, 1993.

Rocha, Ricardo. “Colosio, Baja California y Las Ratas.” El Universal, July 17, 2019.

Székely, Gabriel. “Reflexiones Finales.” In La Economía Política Del Petróleo En México, 1976-1982, 1st ed., 159–70. El Colegio de Mexico, 1983.

Vasquez, M. E. (2018). Los debates electorales en México: ¿una nueva era? Otros Diálogos, (3).