The Abandonment of Indigenous Mexico Through Tourism Development in the 1960s

From the 1940s to the late 60s, Mexico appeared to thrive under the guise of the Mexican miracle—the country’s golden age of capitalism that saw steady economic growth. World War II and the postwar environment allowed for such economic success of Mexico’s industrialization, modernization, and capitalism. Although the economy grew, income distribution worsened as poverty persisted and living standards amongst the rural population deteriorated. The facade of the Mexican miracle and the move towards private enterprise and capitalist priorities abandoned the agrarian promises of the 1910 Revolution, including land reform for indigenous peoples.

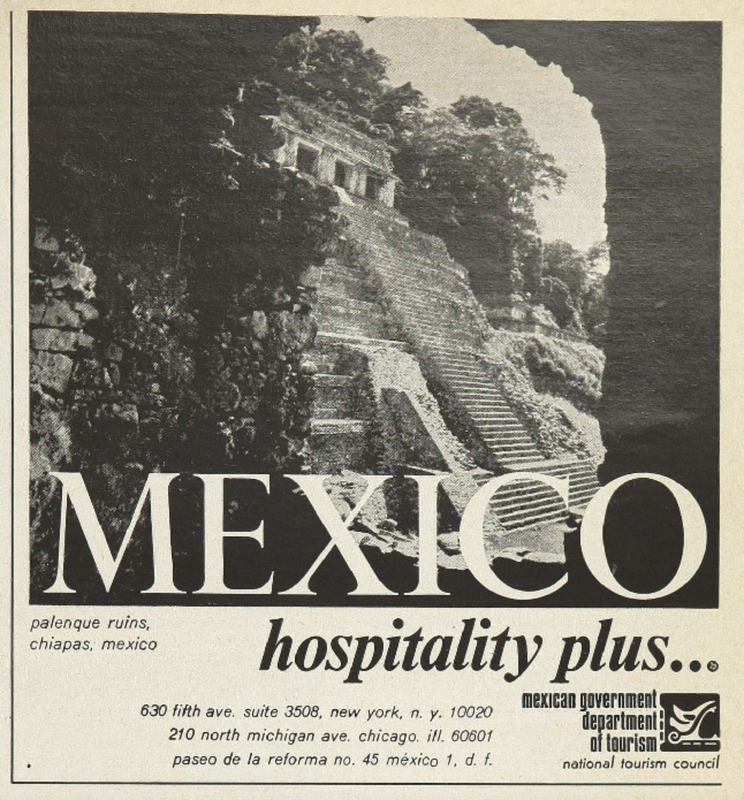

I will explore how Mexico’s tourism development contributed to this failure of land reform. To do so, I will explore advertisements sponsored by the Mexican government or Mexican-owned companies in the 1960s, which reveal the tragic irony of how tourism celebrates Mexico’s indigenous past but hurts the indigenous present.

Tourism development has allowed Mexico to successfully earn foreign exchange, create employment opportunities, and divert internal migration toward tourism development poles. However, in doing so, Mexico has increased its dependency on loans, foreign capital, and foreign patronage—most notably the United States—and has imposed costs on their working class employed in the same low-waged tourist industry employment opportunities. Tourism has become Mexico’s largest service sector and its third highest foreign exchange earnings, at the expense of creating a social and economic apartheid between the industry leaders and the tourists themselves, and the tourist laborers–many of whom are of indigenous descent.

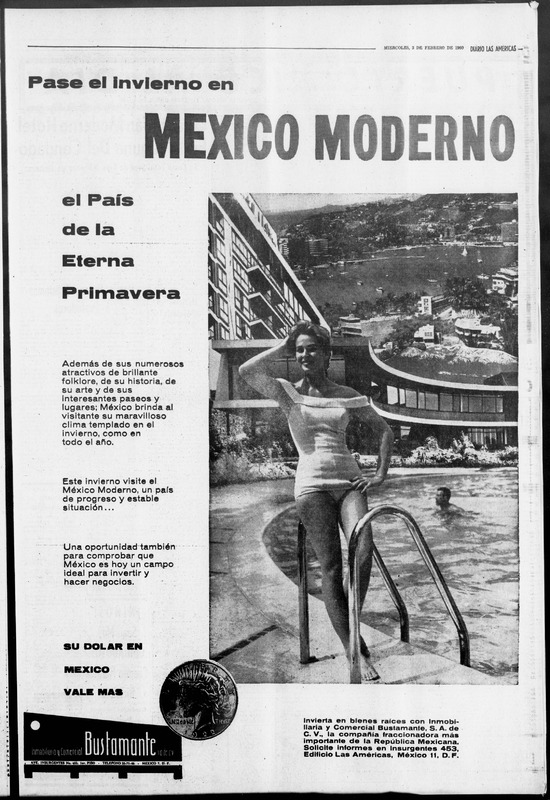

Mexico’s first major success in tourism originated with Acapulco in the 1940s after World War II. Tourist resorts and projects catered for the needs of Americans, particularly encouraging those traveling via cars. Female imagery overwhelmingly dominated the representation of Mexico for its tourist audience, as shown by the ad on the left, dated January 5, 1960.

The ads on the left and right were published in the Díario las Américas, printed in Miami, FL as a member of the Inter-American Press Association. Published daily, it was primarily in Spanish, and was a way for Spanish-speaking immigrants in Miami to stay in touch with international news. These first two ads are presented to Spanish-speaking Americans, and appear to be paid for by the private tourist realty group Grupo Inmobiliario Bustamante. They feature beautiful women in swimsuits with a beach or pool background. With these two ads, Mexico promises a tropical vacation for its visitors.

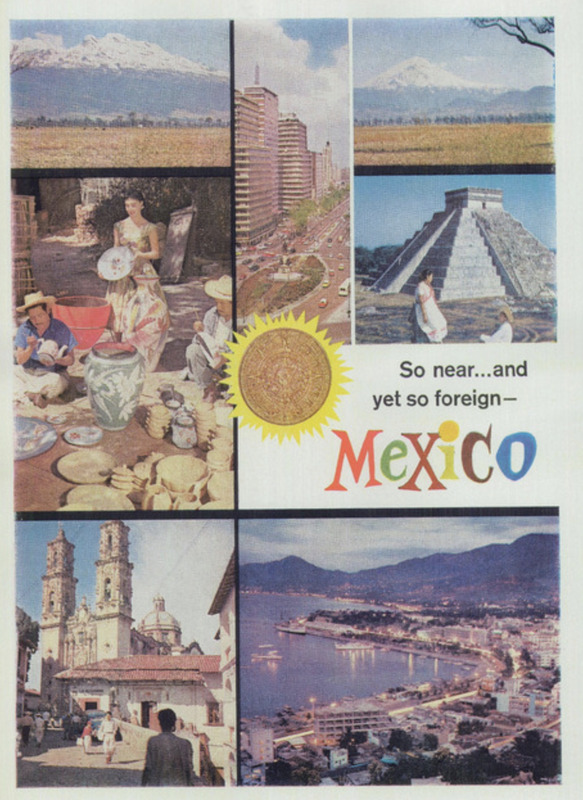

Tourism saw huge growth in the 1960s, where international arrivals grew by more than 11% annually. Not everybody viewed tourism as a purely positive subject: former President Ruiz Cortines publicly cautioned against the negative social impact that international tourism might create, urging Mexicans to maintain “the traditional cultural identity” in tourism zones. Such sentiment is reflected in the upcoming ads, including the one on the left, promoted by the Mexican Department of Tourism in November of 1962. It was published in Town & Country, an American magazine self-advertised as one for “luxury style, travel, and leisure.” There are still women in this ad, but now they are dressed in a traditional Mexican dress. The beautiful young woman on the left panel appears to be in the backdrop of a rural community, surrounded by pottery. On the right panel we see Chichen Itza, a Mayan ruin. There appears to be a couple proposing, with the woman wearing a traditional Mexican dress, and the man wearing a sombrero. With these visuals, the Mexican Department of Tourism started to push a visual of traditional Mexico as the tourist attraction, rather than beaches and women clad in swimsuits.

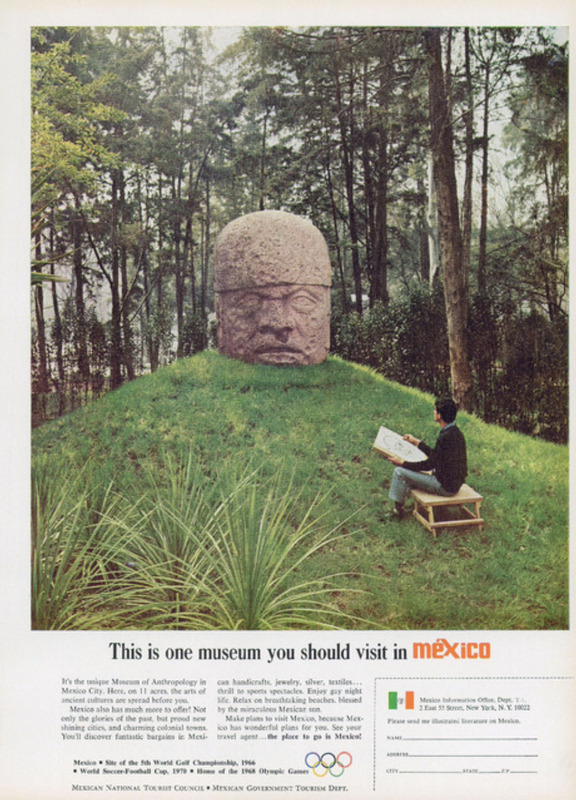

The state was pushing for the success of their tourism industry. By 1964, Mexico’s Department of Tourism had established 15 promotional offices abroad, including 12 in the U.S.. Additionally, the federal government started intervening in local tourist successes like in Puerto Vallarta, where they financed a paved road connecting with the west-coast international highway and an international jet airport in 1965. The federal government recognized tourism as an economic solution for local and regional development, and pushed for more advertisements encouraging Americans to visit and support the industry. The ads around this time celebrated the indigenous through featuring their art, such as this statue shown on the left in an ad from May, 1965.

On the right is another ad from May, 1965, where there is great emphasis on the cheap travel opportunity that Mexico provides. Notice the indigenous face on the black background that draws the viewer’s attention, as well as the inclusion of the sombrero, again pushing a traditionalist Mexican image that focuses on the indigenous and the rural charros—Mestizo cowboys that wore sombreros.

In 1967, Mexico established the National Trust Fund for Tourism Infrastructure in a push for establishing tourism development as part of an economic development strategy. The new projects called for the establishment of 5 poles in 4 of the poorest states with extensive coasts, many of which were occupied by indigenous and rural communities. These projects and the tourism development would lead to the tragic displacement of the indigenous communities that resided there, and break the land reform promise that resulted from the 1910 Revolution.

While the present indigneous Mexicans were bearing the consequences of the industry, the Mexican Government’s Tourist Department continued to push for ads for the Olympics that still celebrated the indigenous past, such as the ad on the left from May, 1968. The athlete mimics the stance of the indigenous sculpture, sending a message of how even with the Olympics, another reason to visit Mexico was the allure of the indigenous history.

With the plans of massive profit and economic success from the tourist industry, local mestizo and indigenous populations found themselves at risk of losing their homes to make space for the resorts supported by the state. For example, 600 small farmers in the tourist area Puerto Vallarta had received around 9,000 hectares of land through the land reform program post-Revolution. Yet, by 1975, only 184 farmers had original rights to land as they had been claimed by tourist businesses. Similarly, Indigenous peoples and rural communities lost their land back at the start of the Revolution. These Mexicans had lived for generations on the tourism-targeted areas and had deep emotional ties to the community and land they occupied—the tension of land-values from the Revolution translated to the 1960s and onward.

This last ad dates to December of 1969, and features Chichen Itza only. There is a sad irony for the subset of Mexicans that this image represents. Chichen Itza reflects a great civilization filled with architectural accomplishments, and represents the indigenous Mayan community that is now used to epitomize Mexico in a one-dimensional advertisement for tourists. This is just one example of how the present day indigenous and rural culture face the consequences of the same industry that exploits their history and identity. Such “double bind” of playing a role in the promotion of economic change but not benefiting from the change itself is not unique to the indigenous in Mexico’s tourism industry. Mexico's 20th century education reforms for indigenous communities manifested without the consultation of the communities themselves. Separately, there was a phenomenon of growing inaccessibility for traditional Mexican foods for the indigenous and other average Mexican citizens while the same foods became highly valued commodities for foreigners due to Mexican economic trends and policy decisions—paralleling the Mexican tourism irony.

This segregation of indigenous and rural communities from American tourists and leaders of the tourist development sector was and continues to be class-based. The economic inequality between the Mexican elite involved in tourism and the resort’s daily service staff is only increasing, raising the question of the true cost of the tourism industry. To feed into the interest of capitalist development as part of the Mexican miracle, Mexico has created and commercialized an image of traditionalist Mexico that takes from rural and indigenous populations—the same people who experience the exclusion and broken Revolutionary promises by the industry—in order to succeed in tourism development.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

"Advertisement: MEXICAN GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM." Town & Country, 11, 1962, 154-155.

"Advertisement: MEXICAN GOVERNMENT TOURISM DEPARTMENT." Woman's Day, 05, 1968, 1.

"Advertisement: Mexican Government Department of Tourism." Woman's Day, 12, 1969, 119.

"Advertisement: Mexico." Town & Country, 05, 1965, 75.

Diario las Américas. [volume] (Miami, Fla.), 03 Feb. 1960. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

Diario las Américas. [volume] (Miami, Fla.), 05 Jan. 1960. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

"Display Ad 155 -- no Title." Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), May 09, 1965.

Secondary Sources:

Alonso, Ana María. Thread of Blood Colonialism, Revolution, and Gender on Mexico’s Northern Frontier. 1st ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995.

Clancy, Michael. Exporting Paradise: Tourism and Development in Mexico. New York: Pergamon, 2001.

“CONOCE Nuestros Proyectos.” Grupo Inmobiliario Bustamante. Accessed March 2, 2022. http://inmobiliariobustamante.com/.

Dillingham, Alan Shane. Oaxaca Resurgent : Indigeneity, Development, and Inequality in Twentieth-Century Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021.

Evans, Nancy H. “The dynamics of tourism development in Puerto Vallarta,” in Emanuel de Kadt (ed.), Tourism: Passport to Development?. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979: 305-320.

Galvez, Alyshia. Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies, and the Destruction of Mexico. 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018.

Joseph, G. M., Anne. Rubenstein, and Eric. Zolov. Fragments of a Golden Age the Politics of Culture in Mexico Since 1940. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

“Luxury Style, Travel, and Leisure - Town & Country Magazine.” Town & Country. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.townandcountrymag.com/.

Padilla, Tanalís. Rural Resistance in the Land of Zapata: The Jaramillista Movement and the Myth of the Pax Priísta, 1940–1962. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. 2008.

Wilson, Tamar Diana. “Economic and Social Impacts of Tourism in Mexico.” Latin American perspectives 35, no. 3 (2008): 37–52.