The Tlatelolco Massacre: Government Illegitimacy

Agitators. Provokers. Criminals. These were some of the names UNAM students were called for fighting against a government that used its power only to abuse its people, exploiting them and silencing them if they so much as dared to speak against their injustices. Tired of oppression, violence, and aggressions against Universities, students confronted an all-around anti-democratic regime forced on the Mexican people by the PRI, which by no means held the moral authority to impose any order on their citizens.

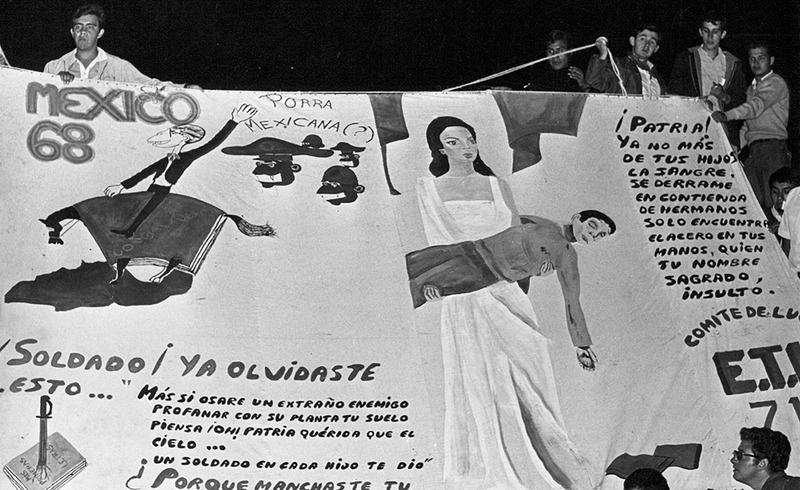

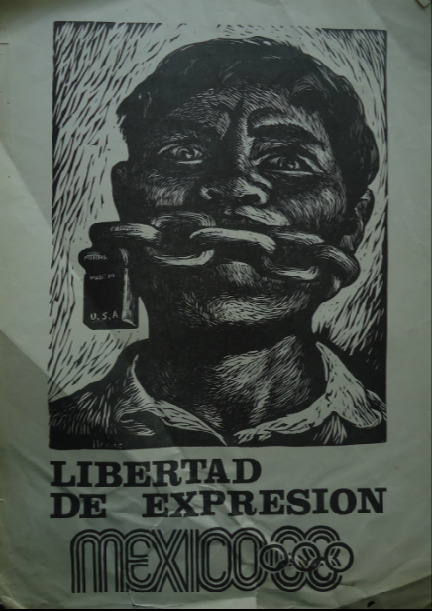

Soon before the Olympics of 1968, which were to be hosted by Mexico, and fed up by the narrative imposed on the Mexican people, UNAM students and those of the Politécnico de México decided to take a stand and protest the continuous instances of abuse and violence executed by the military. They demanded they began respecting the articles of the constitution, their freedom of speech, and their liberty to think and formulate their own opinions - even if they went against the government.

Walking down the Tlatelolco Plaza and chanting "Las represiones las repudiamos porque nos quitan la libertad" (We repudiate repressions because they take away our freedom), the idealist, vibrant middle class students began organizing peaceful demonstrations in July 1968 and, in August, the movement reached "the Golden Age" - the marches were the largest and "most festive".

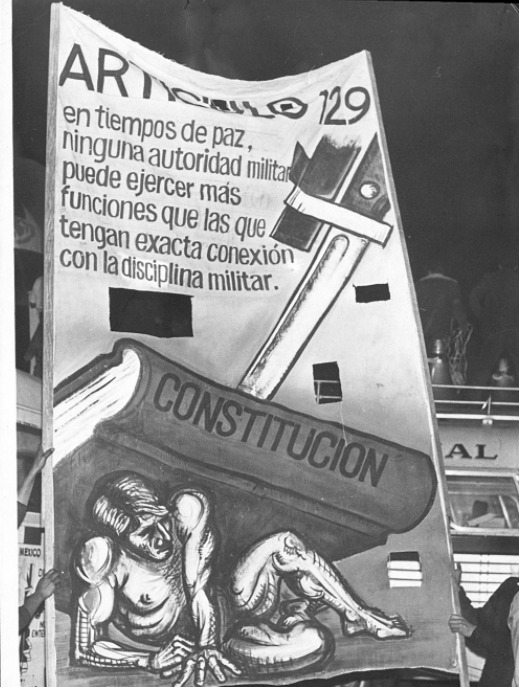

"Article 129: In times of peace, no military authority can have more functions than those that have an exact connectionn with military discipline."

Mexican Constitution (from protest sign above)

Inspired by ideals of social justice, driven by education and culture, students had the following demands:

- Dissolution of the granaderos (grenadier launchers)

- Dissolution of the Article 145, judicial instrument of aggression and opression

- Monetary compensation for the families of those who were murdered or injured in previous protests, starting from July 26th and onwards

- Accountability for the actions of repression, violence, and vandalism orchestrated and executed by granaderos, the police, and the army

These demands, however, were not well-received by the Mexican government. On September 1, 1968, President Díaz Ordaz announced that they would not tolerate any further disruptions of peace, especially given that the Olympics were right around the corner. After this, the students organized the Great Silent March, but the military still, about two weeks later on September 18 invaded Ciudad Universitaria and the government described the UNAM as the "center of subversion". Finally, the Tlatelolco march took place and, as the students began to assemble in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, a helicopter began dropping flares, and soldiers started firing their weapons into the crowd and chaos completely erupted.

Eyewitness's account of the Tlatelolco massacre (1968)"They were firing at us from all directions... A girl came by shouting 'You murderers, you murderers' I took her in my arms and tried to calm her down but she kept screaming... I noticed then that her ear had been shot off and her head was bleeding. The people in the crowd kept piling on top of one another."

Context - The Pax Priísta Myth

During the 1900s, Mexico lived through a period of a “perfect dictatorship”. Under the guise of a democratic government that emerged after the Mexican Revolution, the PRI started the foundation of a regime that would exacerbate the divide between the upper and lower classes through the inability to provide decent and just working conditions to lower-income people.

During Cárdenas's presidency, “workers felt central to the processes of development and saw their salaries rise concomitantly with corporate profits while reaping social benefits.” (Lenti, 33). After his presidency came to an end, however, workers’ daily wages reached the low amount of 18.86 pesos in 1956, though the average figure hovered between 44.61and 57.98 pesos.

This transition of power brought forth dissatisfaction within the Mexican population. At the wake of rising inequalities, the incompetence of an elitist government, and the what Benjamin Smith refers to as dictablanda - meaning soft policies applied to increasingly wealthy employers, effectively letting them operate freely without any control - workers began to demand better wages, and safety, medical, and housing provisions through strikes and protests.

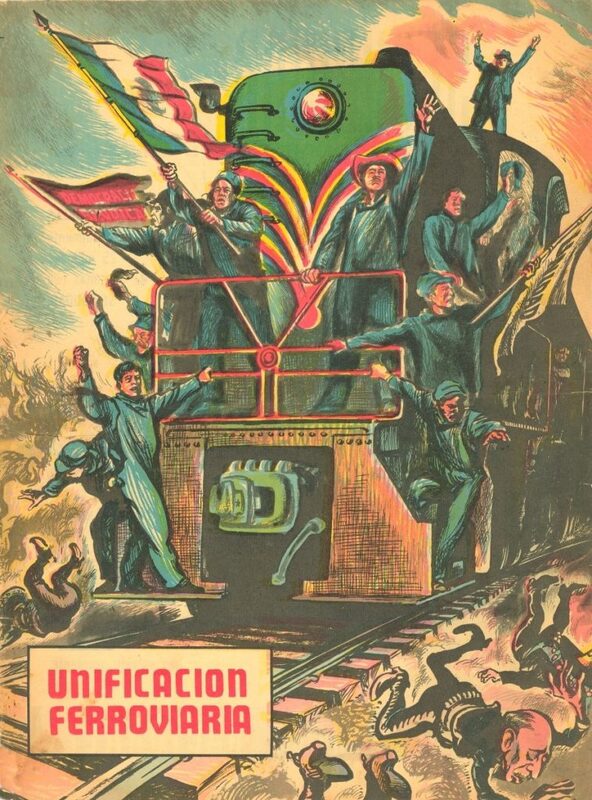

Most of the strikes that were organized prior to the 60s got quickly shot down by the government. For instance, current President Ruiz Cortines, on June 28, 1958, lifted a railroad workers’ strike. He agreed to a 215-peso monthly salary increase. A year later the next president, Adolfo López Mateos, broke up yet another one where “approximately ten thousand workers were fired and eight hundred prisoners taken”.

The arrest of activists such as Vallejo was possible thanks to Article 145:

Mexican Penal Code (promulgated in 1941 and revised in 1950)“A prison term of from two to twelve years and a fine of from one thousand to ten thousand pesos [one hundred sixty dollars to eight hundred dollars] shall be applied to any foreigner or Mexican national who in speech or in writing, or by any other means, carries on political propaganda among foreigners or Mexican nationals, spreading ideas, programs or forms of action of any foreign government which disturb the public order or affect the sovereignty of the Mexican State.

Public order is disturbed when those acts specified in the previous paragraph tend to produce rebellion, sedition, riot, or mutiny.”

The Penal Code also defines the crimes of treason (Articles 124, 125, 126, and 127), espionage (Articles 129 and 130), and other public disorders (Articles 142 and 144). These articles were originally adopted in 1941, during Ávila Camacho’s presidency in order to prevent and criminalize anyone who part-taked in any associations representing systems or regimes contrary to those established, and it was a law that had been adopted by other Latin American countries such as Uruguay and Argentina. These “subversive” associations were seen as a threat against the sovereignty of the state, and it passed in 1941 in Mexico despite some deputy’s opinions, such as that of Trueba Urbina, who thought some of these articles were against freedom of ideas and speech and writing.

Interestingly, there is no official publication of reports for cases decided by the smaller courts that handle cases of this nature. Even when cases are as big as to be handed off to the Supreme Court, records are not easily accessible. Some argue that “denying that the law was framed with the intent of infringing on civil liberties [...] does no more nor less than ‘protect the structure of the Mexican state with the object of allowing the community a peaceful and respectful existence’” (Stevens, 66).

Attention was brought again to these unconstitutional laws in 1968, as a result of the strikes at Tlatelolco. Finally members of the Congress fought to get rid of these laws but ultimately decided to adjourn without settling it. The massacre of Tlatelolco however, did not extinguish student activism. The government, however, did “successfully” shut down many of their protests, and many magazines and newspapers, such as Tribuna Obrera, which were controlled by the PRI, made no mention of what had occurred at Tlatelolco in 1968. Instead, opinion makers “ran a piece entitled “Mission Accomplished” wherein they praised the successful inauguration of the Olympic Games as proof of the nation’s current state of civil and economic stability” (Lenti, 49). According to Lenti (50), “ One need only scan the coverage of the events of 1968 to notice an overwhelming journalistic and editorial bias for the government’s cause over that of the students.” These publications all revolved around the great feat that was hosting the Olympics; they praised the president, the sports players, and the event itself. It was until days later that newspapers such as El Día and Excélsior started condemning the shameful military occupation of UNAM. The former however “showed itself particularly apologetic of civil violence. It reported that the military and police elements responsible for the killings were provoked by agitators and that federal legislators fully justified the use of force, ” defeating the purpose of their publications against the government’s response to the peaceful protests.

Tlatelolco - Constructing Memory

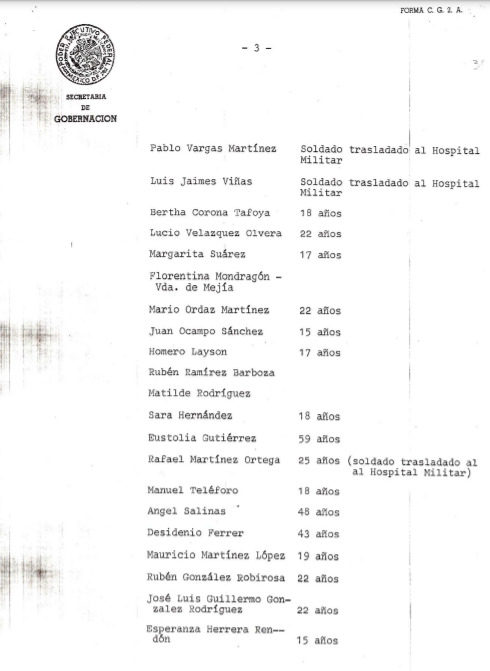

This massacre was a turning point for contemporary Mexican history. As of today, even 54 years after this event, there are conflicting stories and official recounts of what actually happened in Tlatelolco. With a government dedicated to the censorship of subversive movements, several attempts to frame the students and blame them for "revolutionary conspiracies", and known for coercing confessions that would only paint the students in a bad light, it has been difficult to accurately describe what caused this violent response. The erasure of this part of Mexican history later made PAN President Vicente Fox sign a freedom of information law. This law made it possible for many secret military and intelligence documents to go public. The one shown on the left, for example, is an exerpt from the documents that lists the victims of the Tlatelolco massacre along with their age and occupations. For the first time and thanks to the efforts of the Fox administration, there was some accountability and an official count of the victims of October 2nd, 1968. Interestingly and yet not surprisingly, these documents lack organization - the collections include no indices, and they were released only strategically, making it frustrating for anyone who wishes to study them. Even after Archivos Abiertos launched their official records, there seem to be only 44 victims on the National Security Archive's website, although the numbers have oscillated between 200 and 1,500 in books, editorials, articles, and memoirs. It all still feels like a guess, an estimate, and an overall an injustice against the Mexican population, especially for the victims and their families.

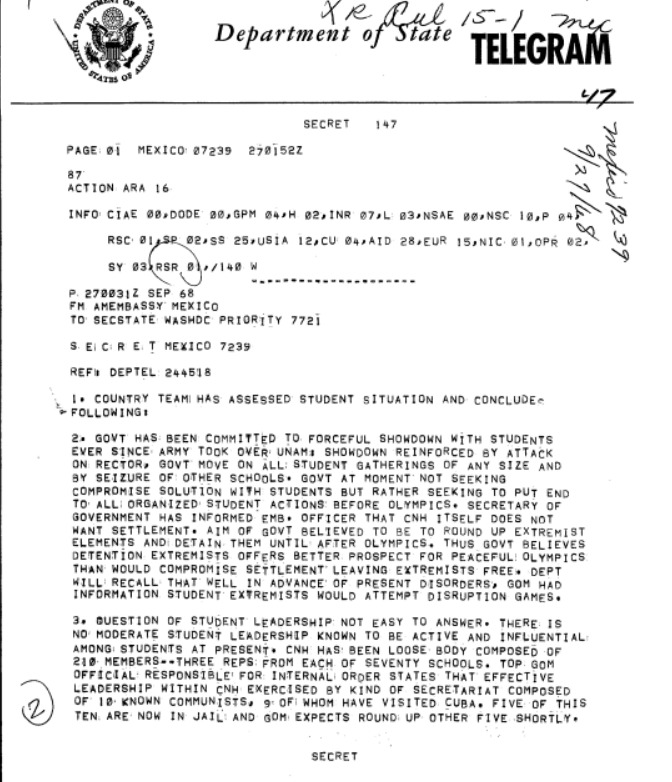

Even foreign documents have gone public, specifically coming from the United States, that help recount the events that occured on October 2nd, 1968. CIA documents showed that the U.S. government was aware of the students' protests, claiming that the communists were behind all these disturbances.

Although all these different perspectives can give us more insight about what truly happened in the Tlatelolco massacre, many of the events that led up to this catastrophic event remain a mystery to the country. However, one thing is absolutely certain: the government finally put an end to what seemed to be a prosperous era, and the Pax Priísta myth came to a tragic end. While it is true that the Olympics still took place in Mexico, there was a large discontent among the population, and it was now more clear than ever how fragile, inefficient, and inhumane the government was.

These events have not been forgotten and, thankfully, the spirits of the students remain strong and vibrant as ever. Several steps were taken forward in terms of political changes that would favor freedom and justice in Mexico thanks to these students and the country will continue to honor them and value them for their work and sacrifice.

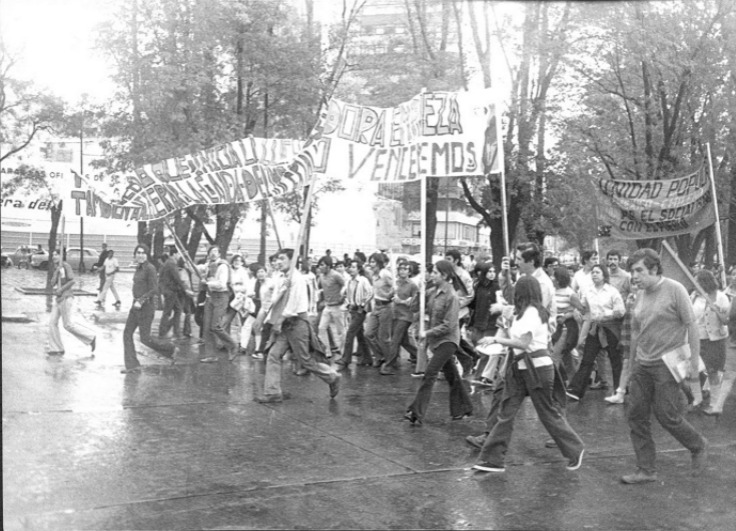

Through the years following the Tlatelolco Massacre since 1968, students have continued to fight and protest against the PRI regime that was in place until 2000. As shown on the image below, taken at a protest in 1972, merely four years after the massacre, students continue to gather and march around Mexico City and in other parts of the country out of solidarity, chanting and announcing "2 de octubre no se olvida" (We don't forget about October 2nd), honoring the lives and the great resilience that has inspired several generations thereafter to fight for their rights and have their voices heard.

Bibliography

Beltrán, Alberto. 1958. Imagen de portada de Unificación ferroviaria. Digital Image. Mirada Ferroviaria.

Academia San Carlos. 1968. Volante, Libertad de Expresión. March 2022. Flyer. Memórica.

García, Marcela. 2019. Portadas de periódicos después del 2 de octubre de 1968. March 2022. Images. Paredro.

UNAM. El Grito. Directed by UNAM students (1969; Mexico City: UNAM), Youtube.

Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM). 1968. Manta de la manifestación estudiantil de agosto de 1968. March 2022. Banner. Memórica.

Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM). 1968. Manta de la manifestación estudiantil de agosto de 1968. March 2022. Banner. Memórica.

Secretaría de Gobernación de México. "The Dead of Tlatelolco: Using the archives to exhume the past". The National Security Archive. 2006.

Harper, L. "The Declassified Record on the Tlatelolco Massacre that Preceded the ’68 Olympic Games". The National Security Archive at George Washington University. 2014.

Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM). 1972. Protesta de estudiantes en un aniversario de la matanza del 2 de octubre de 1968. Image. Memorica.

Berggren, Lauren. “MASSACRE AT TLATELOLCO,” n.d., 5.

Casas, Armando, and Leticia Flores Farfán. “Entre Memoria y Olvido: El 2 de Octubre de 1968.” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 63, no. 234 (August 30, 2018).

Lenti, Joseph U. Redeeming the Revolution. Lincoln, UNITED STATES: UNP - Nebraska, 2017.

Padilla, Tanalís. Rural Resistance in the Land of Zapata: The Jaramillista Movement and the Myth of the Pax Priísta, 1940–1962. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. 2008.

Stevens, Evelyn P. “Legality and Extra-Legality in Mexico.” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 12, no. 1 (1970): 62–75.

Wilton, Samuel. Mexico 1968: Mechanisms of State Control, Tlatelolco, the PRI, and the Student Movement. University of Oregon Press. 2014.