David Alfaro Siqueiros: Communist Before Artist

David Alfaro Siqueiros was born in 1896 in Chihuahua, Mexico and is known to be a key artist in the Mexican muralism movement, which was led by ‘Los tres grandes’ (comprised of artists Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Celemente Orozco). It was following the revolution, from the 1920s to 1950s, when these muralists as well as many others established a style of art that would come to define Mexican identity and nationalism. The muralism movement often involved redefining Mexico’s history and illustrating non-European heroes of Mexico’s past and future.

During this time, many changes occurred in Mexico, including the effects of WWII, U.S. imperialism, and the rise of the communist party. As an artist, Siqueiros was heavily influenced by these events and they would ultimately shape his political views and consequently, his murals as well. This digital exhibit will explore Siqueiros’ identity as an avid supporter of the Mexican Communist Party and its ideals. Specifically, we will take a look at the development of his views towards indigenous people and how this was influenced by his communist ideology, and how the beliefs of the Mexican Communist Party are expressed through his art. We will do so by observing particular murals and primary sources, which ultimately demonstrate that Siqueiros put the promotion of communist ideology above non-political expression.

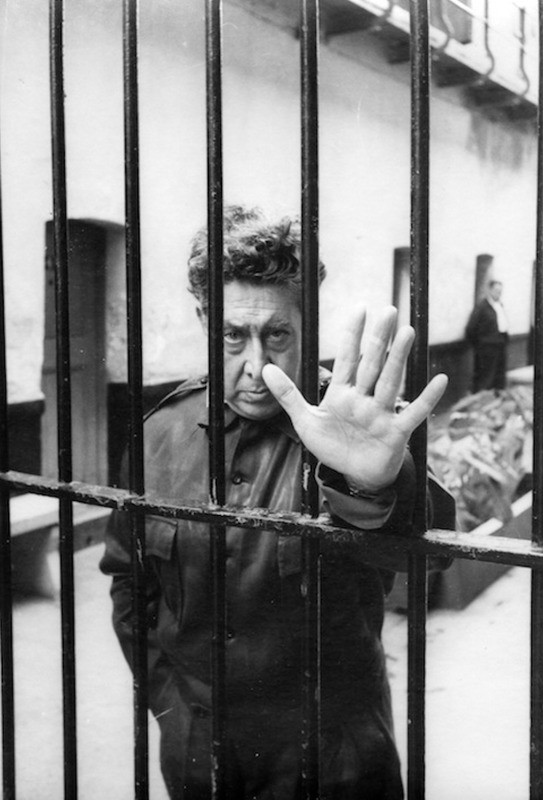

“You know that with me my art is a personal thing, but my party is a duty”

- David Alfaro Siqueiros (1964)

Communism in Latin America: The Context

The success of the Russian Revolution inspired ideas of overthrowing governments controlled by the bourgeoisie and autocrats, and this ideology extended to Mexico. The Mexican Communist Party was founded in 1919 and opposed the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), but was not able to significantly influence the Mexican revolutionary process in the 1920s. Gonzales writes how in the 20s, communist radical movements failed to be organized and be led in a united direction. The party went underground from 1930-1934, but reemerged as aligned with the “Popular Front”.

In 1936 the Popular Front governments in France and Spain were successfully elected. Three political parties made up the Popular Front: the Radical Socialist, the Socialist, and the Communist parties. And they were associated with reformism and anticolonialism. Political leaders of non-European countries were hopeful and viewed this with optimism. The election of the Popular Front gave way to the possibility of working with the French or Spanish government and liberalizing the imperial structure. And after Hitler came into power, fascism became the common enemy.

De Neymet writes about the Mexican Communist Party in the 1940s, and they continued this Popular Front strategy. During WWII, Mexico joined the Allied Powers (against Germany, Italy, and Japan), contributing to the war effort with troops and resources. This was supported by the Mexican Communist Party. However, after the war, the United States — the world’s dominant power of capitalism — established their opposition against the Soviet Union — the world’s center of communism. Therefore, during the Cold War (by the end of the decade and throughout the 50s), the U.S. decided to extend its anti-communist actions to Mexico, affecting the Mexican Communist Party.

In the 1960s, Fidel Castro — communist revolutionary leader — began speaking out more vehemently against “anti-imperialism”. That is, the strategy for combating neo-colonialism in Latin America is prolonged armed conflict. Throughout Latin America, and notably in Cuba, Venezuela, Colombia, and Guatemala, insurgency was growing and guerilla warfare was prioritized.

David Alfaro Siqueiros and the origins of his political views:

Siqueiros was always politically involved, even in his youth. When he was 15 years old at the San Carlos Academy in Mexico, he participated in a student strike to protest its out-of-date methods of art instruction. Siqueiros also served as an officer during the Mexican Revolution before continuing his study of art, and has always considered his art as a vehicle for expressing political and revolutionary thought. His political views were heavily influenced by witnessing the experiences of rural communities during war. In 1974, the New York Times described how in his lifetime, Siqueiros also founded the National Union of Revolutionary Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, served as a union organizer for miners in Jalisco, and edited for a Communist newspaper.

There’s no doubt that Siqueiros was a devout communist. He spent 1930 in jail for organizing a communist demonstration and went into exile in 1932, leaving Mexico for the United States and then South America. Being a staunch supporter of the communist movement, Siqueiros was also influenced by the “Popular Front”, which he supposedly converted to in 1938 while in Spain. The Popular Front would appeal to national pride and history to “mobilize the proletariat”, which can be clearly seen in Siqueiros’ work. His political ideology would ultimately mean that he rejected the capitalist system Mexico was becoming, seeing fascism and imperialism as its inevitable outcomes.

How communist ideology shaped attitudes towards indigenous people

Siqueiros’ attitudes towards indigenous people were ultimately shaped by his communist ideology. Despite depicting indigenous people in his art, Siqueiros did not necessarily support the indigenismo movement and its goals. In his 2009 paper, Fulton writes how Siqueiros condemned ‘folklorism’ and ‘archaeologism’ in modern art and criticized his peers for representing Mexico’s “indigenous past” in an idyllic way — he viewed them as heavily influenced by tourism and “complicit with imperialist penetration into Mexican culture”. For instance, the representation of indigenous people in Siqueiros’ work starkly contrasted to that of Diego Rivera, who would paint idealized scenes of prehispanic life. According to Mary Coffey, Rivera’s vision of historical progress was liberal, but rooted in an idealized Mesoamerican past that was “oriented toward a triumphant and redemptive industrial future.

In the late 1920s, Siqueiros campaigned against Rivera’s ‘folklorism’ and advocated for a return to radical politics. Siqueiros’ criticism of Rivera also stemmed from Rivera’s “opportunism”, as he painted for U.S. capitalists and the Mexican ruling party. Although it can be argued that Siqueiros wanted to portray indigenous life in a more genuine way, he was ultimately a communist. That is, he saw revolution eventually occurring through the industrialized proletariat. This meant that for him, the indigenous were ‘othered’ and treated as the lower class, with the solution being to integrate the indigenous into the modern economy as workers. Ironically, this seems to be more aligned with the economic policies of the Mexican government during his time.

One of the purposes of the Mexican muralism movement was to express a unique national identity (ie. mexicanidad), which is based on a history of indigenous culture. It also reflected the favorable post-conquest racial and cultural mixing (ie. mestizaje), eventually ending with an industrialized Mexico. Despite being a prominent figure in this movement, Siqueiros decided to utilize indigenous characters in his murals to express a different message. It was a message of anti-imperialism and of a tragic, destructive past caused by the European — a perspective that the Mexican Communist Party held.

América Tropical (1932)

América Tropical (1932) depicts a crucified indigenous person at the center, with an eagle perched on top, a symbol of the United States. Behind, a Mayan temple is being overtaken by nature, about to be forgotten. Apparently, Siqueiros was commissioned to paint a romanticized, idealized version of “tropical America”. Instead, he saw “tropical America” as a land of indigenous and African people who had been “persecuted and harassed by their respective governments,” as he mentioned in a 1971 interview. This mural is important because it clearly demonstrates Siqueiros’ break from the ‘folklorism’ and ‘picturesqueness’ that he highly criticized. Through this mural, he was able to separate indigenismo from folklore, portraying history as what he thought it to truly be.

According to The Getty Conservation Institute, the mural was also ordered to be whitewashed and was only reopened in 2012, which is essential to note. During the time of its creation, many Mexicans in the United States were being deported to Mexico. In addition, “Red Squads”, intended to infiltrate and counter political groups such as communists and anarchists, were becoming more common. Therefore, Siqueiros painted this mural as a direct response to these events, once again combining politics and art.

Muerte Al Invasor (1942)

This piece is titled Muerte Al Invasor (1942), which translates to “death to the invader”. It depicts a very dramatic scene of the Chilean indigenous people in their struggle against the Spanish conquistadors. This piece is notable because before WWII, Siqueiros used to only speak of it in terms of anti-imperialism. However, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Siqueiros began advertizing it as an anti-fascism piece. Again, the indigenous life is not portrayed as idyllic, but rather a struggle and constant clash with the west. This piece was the first of Siqueiros’ murals to depict a national hero, which aligns with the Popular Front strategy of utilizing nationalism and historical figures. During this time, he continued to encourage the anti-fascist coalition as Popular Front ideology permeated in his art.

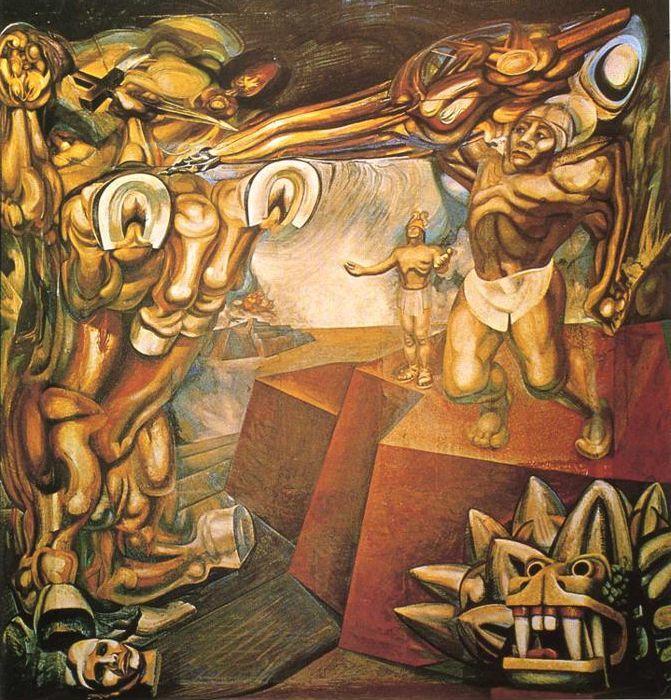

Cuautémoc Against the Myth (1944)

This piece depicts a battle between Cuautémoc, who was the last Aztec emperor, and a centaur, who represents the Spanish conquest and Christianity. We can note that Centaurs traditionally represent the “uncivilized” in art. Siqueiros considered this piece one of his most important, and he utilized the narrative in his painting to support his political agenda as a communist.

Siqueiros returned to Mexico from exile at the beginning of 1944, promising to not engage in oppositional politics and devote his work to promoting the war effort. However, he began Cuautémoc Against the Myth secretly, clearly demonstrating that politics were his priority. When talking to the press, Siqueiros suggested multiple interpretations of the painting. During WWII, the mural symbolized a nation armed for self-defense and protecting democracy. He related this to Mexico’s involvement in WWII, when the nation was aligned with the Allied Powers. However, after WWII — when the U.S. was cracking down on communist activities, even in Mexico — the mural symbolized the struggle against western colonialism and capitalist domination. In 1963, Siqueiros even stated: “I see Cuautémoc a prototype of Mao Zedong…”, calling his painting an “anti-imperialist mural”. Later, Siqueiros asserted that Cuautémoc represented the will to defend Mexico’s autonomy and continue the revolutionary socialist program. It’s clear that Siqueiros’ message in Cuautémoc Against the Myth was constantly evolving to be consistent with the Mexican Communist Party’s agenda.

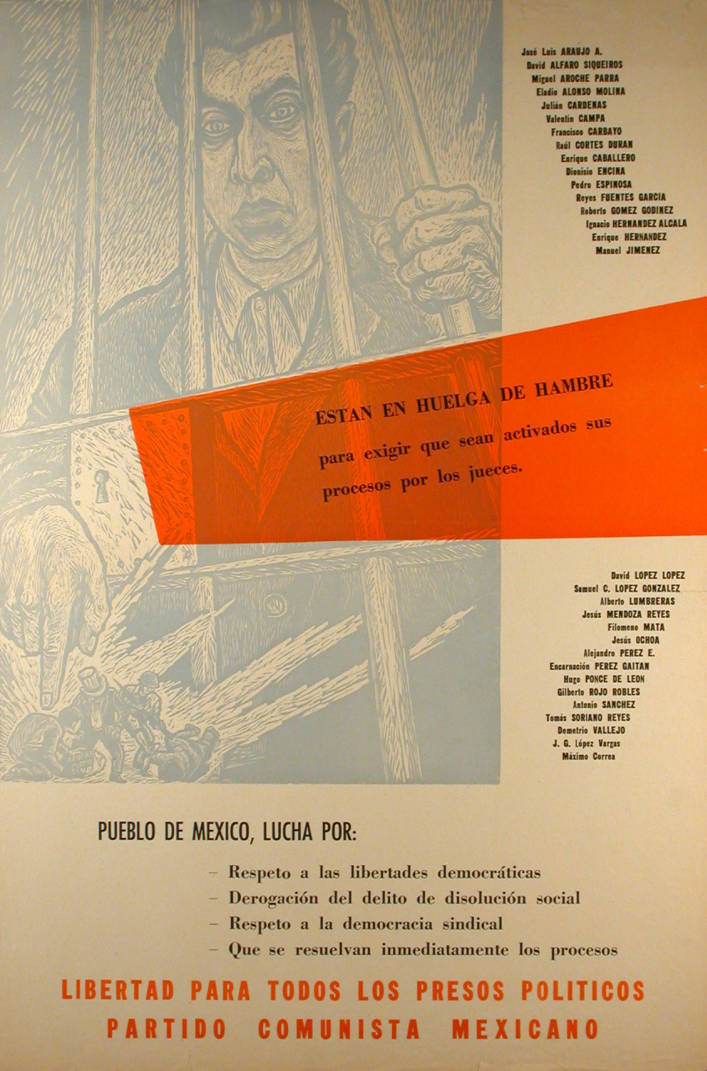

Están en Huelga de Hambre (1960s)

This poster is titled “they are on hunger strike” (1960s) and was produced by the Taller de Gráfica Popular — an artist’s collective that primarily used art to advance revolutionary social causes, including posters of Mexican heroes, culture, and leftist political movements. This particular poster was created in conjunction with the Mexican Communist Party to announce the fifteen artists on hunger strike to bring awareness of Siqueiros’ imprisonment. This poster demonstrates Siqueiros’ prominence in the communist party as well as his dedication to his political beliefs. This poster encapsulates that politics was his first and foremost priority, as a citizen of Mexico and as an artist.

In summary, David Alfaro Siqueiros was greatly influenced by the Mexican Communist Party and its political efforts, including its involvement in the Popular Front. Beginning in the 1920s with his criticism of “folklorism”, Siqueiros would portray indigenous people in his paintings to promote a message of anti-imperialism. Throughout the 30s, he painted in response to political turmoil and continued to counter the rhetoric of an idealized indigenous life. Once WWII began, Siqueiros spoke of his pieces in terms of anti-fascism as well, aligning his work with the Popular Front. Post-WWII included opposition to the growing influence of capitalism, specifically from the U.S. We can see that these different stances were all aligned with the messages of the Mexican Communist Party during the time, ultimately demonstrating that Siqueiros prioritized his political party and the communist agenda so much so that it became who he was as an artist.

Bibliography

Primary sources

García Bustos, Arturo. Están en Huelga de Hambre. Image. New Mexico Digital Collections. August 23, 2007.

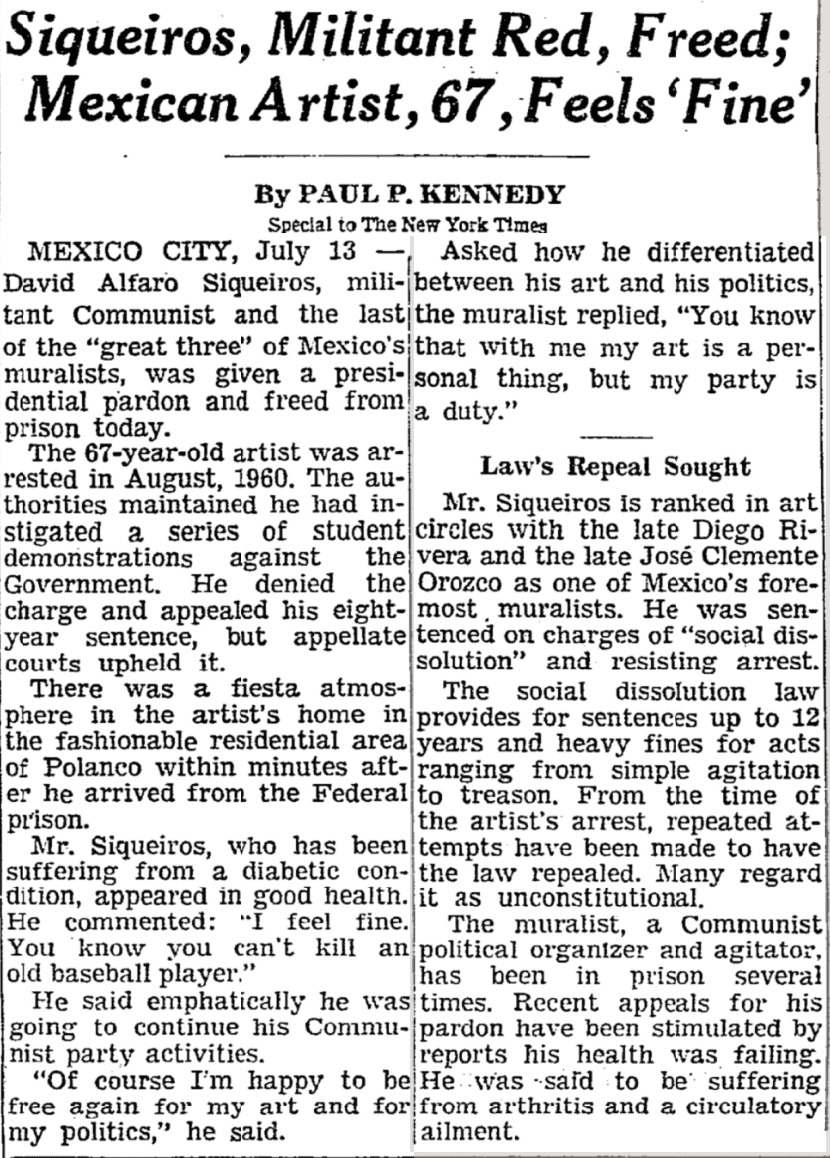

Paul Kennedy, "Siqueiros, Militant Red, Freed; Mexican Artist, 67, Feels 'Fine,'" The New York Times, July 13, 1964.

Siqueiros, David Alfaro. América Tropical. Image. Npr.org.

Siqueiros, David Alfaro. Cuautémoc Against the Myth. Image. artres.com.

Siqueiros, David Alfaro. Muerte al Invasor. Image. wikiart.org. December 2, 2011.

The Getty Research Institute. Original América Tropical in the 1930s. Photograph. Getty Research Institute.

Secondary sources

Cohen, William B. “The Colonial Policy of the Popular Front.” French Historical Studies 7, no. 3 (1972): 368–93.

“Communist Activities in Latin America, 1967.” Communist Affairs 5, no. 4 (1967): 20–22.

De Neymet, Marcela. “Cronología del Partido Communista Mexicano.” Mexico: Ediciones de la Cultura Popular, 1981.

Del Barco, Mandalit. “Revolutionary Mural to Return to L.A. After 80 Years.” October 26, 2010.

Fulton, Christopher. “Siqueiros against the Myth: Paeans to Cuauhtémoc, Last of the Aztec Emperors.” Oxford Art Journal 32, no. 1 (2009): 67–93.

Goldman, Shifra M. “Siqueiros and Three Early Murals in Los Angeles.” Art Journal 33, no. 4 (1974): 321–27.

Gonzales, Michael J. “Stumbling Its Way Through Mexico: The Early Years of the Communist International by Daniela Spenser (review).” The Americas 70, no. 3 (2014): 565-566.

The Getty Conservation Institute. “Conservation of América Tropical (1988-2012).” August 2019.

The New York Times. “Siqueiros, Muralist and Exponent of New World Proletarian Art, Dies at 77.” January 7, 1974.