The Role of the Bracero Program in Redefining Mexican Gender Norms

The Bracero Program, also known as the Federal Guest Worker Program, was a collaboration between the United States government, the Mexican government, and agricultural companies to facilitate the temporary immigration of Mexican laborers onto American soil between 1942 and 1964. Fueled by a desire for cheap labor and a tightened grip on migration to the United States, the American government heavily promoted the Bracero Program. Simultaneously, the Mexican government believed that the program was a solution to widespread unemployment in rural areas and that wage remittances would stimulate economic growth. Most research on the Bracero Program focuses on the exploitation of braceros, almost exclusively men, who were subject to wage theft, racial discrimination, and abuse at the hands of agricultural employers. A lesser known narrative is that of the rural Mexican women who were left behind, forced to contend with the physical, financial, and emotional burden of managing their families and communities. Although women were pushed to adopt novel gender roles in the public sphere, I argue that the effects of the Bracero Program were in line with patriarchal norms, given that these changes were driven by severe exploitation and that the largely apolitical responses of Mexican women to this exploitation mirrored traditional gender expectations.

Recruitment and Lived Realities Across the United States Border

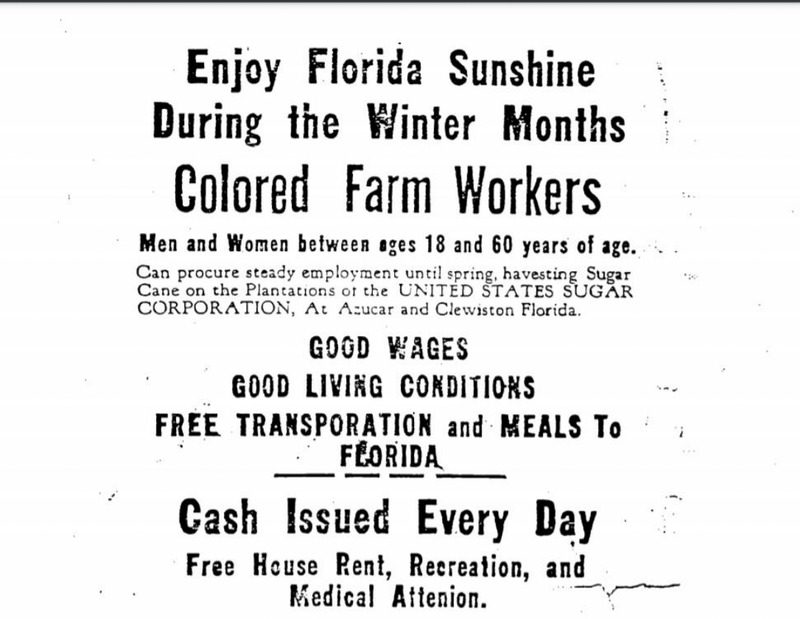

Recruitment into the Bracero Program required a massive propaganda outreach. Posters produced by the American government, such as the one on the left, advertised high wages, good living conditions, temperate environments, and the promise of immediate cash to rural Mexican men. Additional propaganda was produced by the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) during this period with claims that the Bracero Program would instill positive labor values in rural communities. Decades of government-led urban development had left rural Mexico in a state of financial desperation; the need for money coupled with the propaganda-induced belief that they would be paid fair wages led to over 5 million Mexican nationals making the challenging decision to migrate to the United States as braceros. However, migration decisions were typically made unilaterally by the male head of the household, failing to consider any impact on women.

Lived realities for Mexican men differed significantly from the promises made by the propaganda. Testimony compiled in the form of oral archives by Mireya Loza, author of Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political Freedom, demonstrates that braceros were subject to high degrees of exploitation in the United States, often subject to racial discrimination, wage theft, and abuse at the hands of large agricultural corporations. Bracero men would engage primarily in stoop labor, the physically-intensive process of manually planting and harvesting crops shown in the image on the right. With stoop labor becoming increasingly expensive, agricultural corporations were incentivized to hire poorly-compensated braceros to work 12-16 hours on average per day in high heat. Men were paid on average $2.50 per day on farms such as John Jacobs Farm in Tucson, Arizona, less than three quarters of their white counterparts on equivalent farms. Worse, stories from women in towns like San Martin de Hidalgo suggest that many women in bracero families failed to receive these meager wages due to wage theft along transit routes to Mexico.

At the time, the only legal recourse for braceros was through labor unions such as the United Farm Workers and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peoples (NAACP), which both fought for better working conditions for braceros in the early 1960s. However, braceros resisted their oppression through extralegal channels as well. Loza’s compilation of oral histories showcases how braceros celebrated their indigeneity in the face of assimilation, organized grassroots labor movements to demand fair wages, and embraced their sexual desires (often outside of hetersexual norms) in defiance of the dominant narrative of bracero men being mestizo, family-oriented subjects of the Mexican state. It is important to note that bracero men living across the border resisted exploitation through both political and social defiance in contrast to women in bracero families who organized socially but remained largely silent in the political sphere, a gendered response that will be explored further below.

Lived Realities for Women in Bracero Families

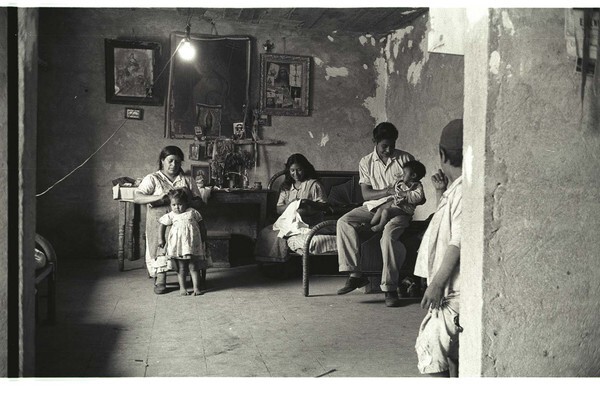

Women were often forced to adopt the role of sole caretaker in Mexican families, supporting themselves and their children emotionally and financially. Wage gaps, a lack of remittances from bracero husbands, and little government assistance caused severe financial burdens. Children growing up without a father figure caused severe emotional burdens which mothers had the sole responsibility to assuage.

In rural towns like San Martin de Hidalgo, Jalisco, women in bracero households were estimated to work more than 14 hours daily, support 2 to 3 jobs in addition to household chores, and care for 2 to 8 children on average. The wage gap in Mexico at the time meant that women made, after all these hours, less than half of what the average Mexican man would make in those same positions (roughly $2 USD per day). The emigration of over 5 million men from rural communities devastated the formal economy in Mexico, forcing women to engage in positions in the informal economy, exchanging clothing, food, toys, and household products between community members. We observe the impact of intersectionality on the financial burdens imposed on Mexican women: the combination of gender and physical position in the devastated rural Mexican economy resulted in a vast wage gap between bracero men and the women in bracero families.

The interactions of women with the bracero program would largely be along patriarchal lines. Women in Monterrey, Mexico, along the border with the United States were responsible for serving bracero men food and water as they embarked northwards. Despite their increased role in the public sphere and their newly acquired status as heads of households, much of their labor occurred in exploitative conditions, along gendered lines, and without their consent.

Women’s Reactions to the Emotional Turmoil Caused by the Bracero Program

During this challenging historical moment, women in bracero families leveraged both local community building and transnational communication to maintain healthy relationships.

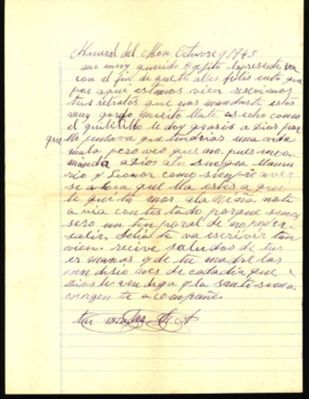

Letter-writing was a common technique Mexican women used to stay connected with their male relatives abroad. These letters detailed their lives and expressed blessings for their fathers, husbands, or sons that were often unrequited. Bracero men sometimes failed to receive these letters due to the difficulty in sending international letters at this time; many that were actually delivered never received a response. In this letter, a mother writes to her son, Salvador, her gratitude for him sending her a picture of himself in the United States where he looks healthy - she even calls him “gordo” in a light bit of teasing. A common phrase both in this letter and others was “que dios te bendiga,” expressing the women’s fears for the well-being of their male relatives and their desire for them to return safely. One recurring omission from these letters is any form of complaint from women in bracero families regarding their burdensome circumstances. Women were encouraged by community officials to refrain from discussing their personal griefs to prevent braceros from returning before the end of their contract term.

Although letter-writing provided for interpersonal connection, women in many communities, including San Martin de Hidalgo, would need to manage their emotions through desahogarse, or releasing their feelings of anger and hurt in group settings. During these community meetings, women also began to coordinate efforts to feed their families, find jobs, and hold community fundraisers, demonstrating a level of sacrifice and dedication that would leave a lasting impression on their children. The lack of wage remittances and government intervention to support bracero families pushed women to mobilize their communities and provide for themselves, a unique effect of the Bracero Program that defies prior gender expectations. Dr. Ana Elizabeth Rosas, author of Abrazando el Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Border, argues that community mobilization empowered women to confront the oppressive reality imposed upon them by the Bracero Program. However, when comparing the actions of bracero men to women in bracero families, we note that men had the opportunity to resist oppression through national political and social channels, while women were relegated to local social efforts in order to support their communities. Instead of criticizing the bracero program’s failures or the systemic barriers that led to their exploitation, women directed their attention at protecting their communities from disruption, managing their relationships with their children, and focusing on financially supporting their families. While these actions are laudable, they are in line with patriarchal values that demand that women do not engage in political topics and remain silent in the face of oppression.

Finally, a minority of women in bracero families crossed the border in search of economic opportunity and/or their male relatives. Testimonies from San Martin de Hidalgo suggest that many of these women were from bracero households where male relatives failed to send remittances or whose remittances were stolen during the transfer process. It is important to highlight the experiences of these women and how exploitative conditions forced them to migrate North, adopting novel gender roles in the public sphere.

The Bracero Program and Changing Gender Norms: Feminist or Patriarchal?

Overall, although women in bracero families became heads of the household during this period and entered the public sphere, the exploitative labor they had to perform both in the household and in the workplace combined with responses that followed traditional gender norms demonstrate the continued effect of the patriarchy in Mexican society. Critically, while bracero men resisted their oppression through the political channel of labor unions, in addition to their social reclamation of indigeneity and sexual agency, women in bracero families engaged in resistance by forming community organizations, providing a social space for emotional healing and collaborative financial efforts. Although both forms of defiance are valuable, the idea that political resistance is reserved for men demonstrates the pervasiveness of patriarchal gender norms during this period. The Bracero Program dramatically impacted the lived realities of Mexican women because of the financial, social, and emotional burden imposed on them by the departure of Mexican men to the United States, but these changes should not be considered a feminist advance as forms of resistance remained highly gendered.

Primary Sources:

Leonard Nadel, "Women prepare food and drink for braceros as they wait to be processed through the Monterrey Processing Center, Mexico.," in Bracero History Archive, Item #1347, (accessed February 17, 2022).

Leonard Nadel, "Women work and care for children in a braceros family home in San Mateo, Mexico.," in Bracero History Archive, Item #1498, (accessed February 17, 2022).

Jubilee Magazine, April 1957. Original caption: “Stoop labor”

Undelivered 1940s Mexican letters to Pacific Northwest relatives. Stanford University. Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives

Collection WJC-DPC: Records of the Domestic Policy Council (Clinton Administration), ca. 1992–1/20/2001. National Archives Identifier:158701046

Maricopa County, AZ. Mexican girls bunching broccoli; they earn about $2.50 a day. John Jacob's farm. Local Identifier: 16-G-159(2)AAA8172W

Secondary Sources:

Loza, Mireya. Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political Freedom. The University of North Carolina Press, 2016. https://uncpress.org/book/9781469629766/defiant-braceros/

Rosas, Dr. Ana Elizabeth. Abrazando el Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Border. University of California Press, 2014. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/35643.