Work as a Cultural Entity

“I’ve done this for a long time so I’m used to it, crowds make me happy, and I also get a chance to chat with the students. It makes me feel younger and relaxed, and I forget how tired I am. That’s one of the good things about this job. And anyway, I have no choice but to accept it. I’m used to it, and the job remains the same, so you have to find ways to make it more enjoyable, of course! That’s how life is! There’s no use complaining; it’s best to be happy. Whether you’re working at a temporary job or a permanent one, you have to remember to always love and value your work.” – Hung, bus fee collector

Examining Work Attitudes in Vietnam

As a microcosm of the country, Saigon serves as a useful case study through which to examine understandings of work in Vietnam overall. With is tall colonial buildings hosting the major players of its most robust industries (with textiles and manufacturing foremost among them), and its streets bustling with servicepeople of all trades, the city is imbued with a distinctly enterprising spirit. Saigon’s unique character is always palpable but is perhaps most explicit at rush hour. When the clock strikes and an onslaught of motorbikes fills the roads, they do so with the kind of kinetic energy that can only be emitted by a spirited workforce itching to reach its next destination. My research has revealed that those commuters likely regard their daily occupations with the same tireless engagement that they do traffic jams. Indeed, in both cases, the laborers of Saigon appear to expect a considerable amount drudgery. In Saigon, work is regarded as such. The assumed slog of the average workday is widely acknowledged and has prompted its laborers to assume a unique ethic of pragmatism in the professional context.

This ethic is characterized by the supposition that work necessarily entails a certain degree of difficulty and has thus undermined its ability to strain or torment workers. Economist Thang van Nguyen demonstrates this notion in his study examining work attitudes in Vietnam. Nguyen found that overall, Vietnamese workers reported levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment that were closely comparable to those of American and Japanese workers. “These findings are particularly interesting,” he notes, “since the Vietnamese employees received significantly lower income from their work.” The study is just one demonstration of the influence that cultural perceptions of labor have on the quotidian life of the average worker in Saigon.

This relation to work is likely compounded by the memories Vietnamese workers have of the pre-Đổi Mới period. Most of the employees interviewed for Nguyen’s study conceptualized their economic position as better than those of their elder family members and friends during the latter half of the 20th century. Positive work attitudes were thus strengthened by a collective appreciation for the nation’s transition to a market-based model. In this way, the proliferation of a distinctly Vietnamese work ethic is a deeply social process.

This sociality bookends the proliferation of this work ethic in Vietnam. In addition to contributing on the front end, by allowing employees to perform favorable comparisons to the work conditions of decades past, studies show that positive work attitudes are somewhat contagious. Through their survey of 300 employees in Saigon’s tourism sector (including hotel and restaurant employees, travel agents, and tour serve operators) Mai Ngoc Khuong and Nguyen Vu Quynh Nhu at Vietnam National University identified employee sociability amongst the most crucial factors to the maintenance of organizational commitment. “There was a predictable relationship,” they found, “between employee commitment and employee emotional intelligence, employee sociability in particular.” These findings demonstrate the somewhat intuitive fact that positivity breeds positivity; individual levels of job satisfaction grow in environment where people generally appear engaged and willing to do their work.

This notion is reinforced by another study conducted by Mai Ngoc Khuong and Phan Le Vu, this time investigating the organization commitment of about 300 drivers in Saigon. Once again, the research found that positive relationships were positively related to levels of job satisfaction. It is worth noting that the study unsurprisingly identified positive relationships with managers as particularly influential. Even in the case of low earnings or subpar work conditions, then, interacting with sociable colleageues at work serves to improve morale and make the day pass by more quickly. While this is particularly true for employees of larger businesses, these findings demonstrate that workers can also benefit from interactions with other independent laborers or customers they might interact with throughout their shift. This ethic of pragmatism is thus both derived from and spread through the sociality of the Vietnamese workplace.

In short, this unique feature of Vietnamese attitudes toward work has consequently resulted in a labor force that is conditioned for consistently long hours. This assertion is not valid without due qualification. Vietnamese laborers, particularly those among the working class, do not possess any particular characteristics beyond the aforementioned occupational ethos, that makes them particularly suited to grueling labor. The effects of subpar work conditions unquestionably affect them. Cultural attitudes and understandings of work in Vietnam have thus served to mitigate the toll strenuous work can take on its laborers.

Examining Work Attitudes in Vietnam

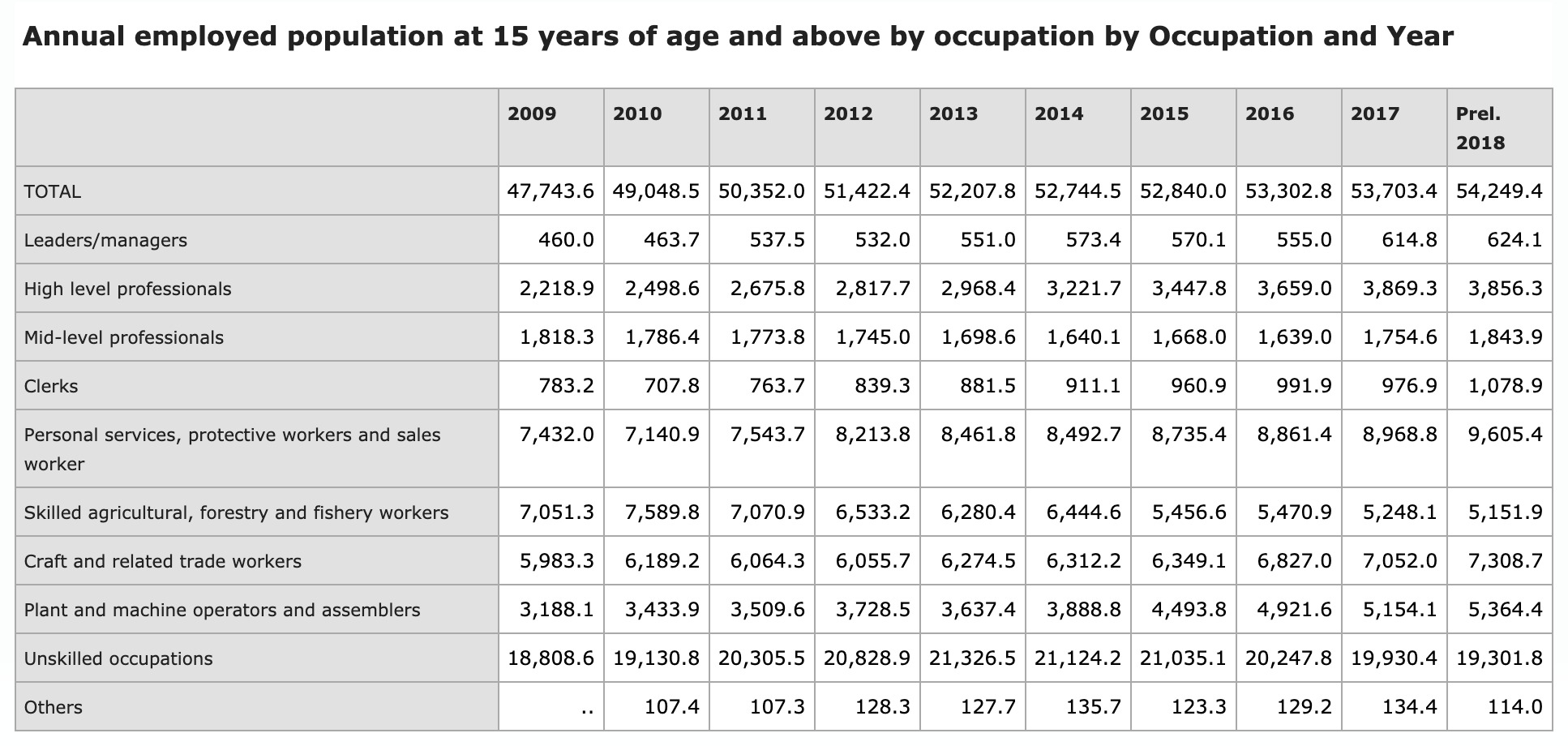

The following figures were provided by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam and are intended to paint a more detailed picture of the Vietnamese labor force. The tables below contain breakdowns of the Vietnamese labor force by gender, industry, occupation, and seniority level and will further contextualize the oral testimony discussed below.

Speaking Out: Work Narratives from Urban Spaces

The work culture outlined above is evident in the oral testimony of working-class laborers in urban Vietnam. The following section will examine the way three workers across the service industry Vietnam tell the stories of their lives and work. These narratives serve to highlight how work attitudes inform self-image and broader conceptions of success. Taken together, they offer genuine examples of the pragmatic ethic described earlier.

Mary Hong, Nail Technician

Below is an excerpt from the interview I conducted with Mary Hong this past February. It describes her childhood memories of Saigon, where her mother opened a pho noodle restaurant in the suburban district of Gò Vấp. Mary recalls her mother’s schedule and the ways in which she would help her as a student:

HONG: Yeah, she very good cook. She work very hard. She opened the restaurant in the morning around 3:00 AM. And she in the morning she served for the breakfast for the pho noodle soup for a lot of people [who bought breakfast] before they go to work. And after that she served for the lunch, white rice and many food. And at nighttime she cook for the soup. Yeah, she work all day in restaurant.

ARMAS: Would you guys be on your own in the evenings after school to take care of yourselves, or would you all go to the restaurant and help her?

HONG: Yeah, I wake up very early and I help her a little bit in the morning before I go school. And after I go – after around maybe noontime, I back from school and I stay in restaurant. I help her until at night we go back to home together.

Mary was matter-of-fact in her recollection of her childhood and adolescence working shifts in the back room of her mother’s noodle stall. While she fully acknowledged the extent of her mother’s industriousness, she seemed to assume that such grueling work was the natural result of her mother’s status as a widow. That resignation extended to her own contributions to the restaurant as a student. Delivered with a shrug, this excerpt indicates that even as a child, Mary considered the help she provided her mother as nothing more than a pleasant introduction into the working world. For her, this was the first in a series of occupations to which she would likewise dedicate large parts of her life.

Son, Cyclo Driver

Son’s testimony, taped in an interview perofrmed by filmmaker Samuel Hefti, lends credence to the importance of comparison in determining attitudes toward work in contemporary Saigon. As a cyclo driver, Son operates an independent transportation business via a three-wheeled bicycle with a passenger seat at the machine’s front. As a former ARVN soldier, Son’s experiences working in modern Saigon are intimately informed by his experiences in the pre-Đổi Mới period and his memories of War itself. This following interview (the full version of which can be viewed here) excerpt substantiates this claim:

“35 kilomter minimum for one day - sometimes 55!Sometimes people take me around and around, one hour or two hours. I go to museum, market, Saigon River, Notre Dame – everywhere…I’m lucky. I’m lucky for the War before. Many friend with me in the army, he not lucky. He dead. Me lucky. I have one bullet in my leg. VC, Viet Cong, try to kill me. I’m lucky.”

Son’s interview was particularly interesting in that he only mentions works at its opening and closing. While it began with his recognition of the physical demands of his job, he quickly transitioned into a description of his War experiences. The fear and uncertainty of that period in Son’s life culminated with his shooting and subsequent imprisonment by northern Vietnamese forces for two years. The mention of these experiences prompted him to continually repeat the phrase “I’m lucky.” For Son, the grind of daily weighted 34-mile bike rides is nothing compared to the risk he faced in his youth.

He does not mention his occupation again until the interview’s conclusion. Son then expresses hope for a better job in the future, perhaps as a tour guide which he states yields more profit and would complement his skill in English. Rather than voicing a hope of retirement or an immediate change in occupation, Son appears to be a contented worker enjoying his responsibility to his family. Son’s gratitude is the direct product of his wartime experiences, resulting in the positive work attitudes that characterize Vietnamese professional pragmatism.

Vinh, Hot vit Lon Street Vendor

Vinh is a street vendor specializing in three different types of egg: hot vit lon, cut lon, and hot vit dua. Vinh moved with her husband to Saigon in order to put her son through school. In her interview (which can be viewed here) Vinh did, in fact, express a certain amount of discontent with her occupation, as evidenced below:

“I walk non-stop from 2:30pm till midnight, but not sure how many kilometers…I moved to Saigon to sell Hot Vit Lon, to make money for my child to go to college. My son goes to college in downtown Hanoi, so my husband and I had to move to do this. This business is very difficult in many ways, but if I didn’t do this I guess I would have to go back home…”

However, as she delivered these statements, she could not suppress the laugh upon her lips. The apparent disparity between Vinh’s perception of her own reality and her emotional reaction to it suggest that to her, it is well worth it remain in Saigon and work hard than to return to her hometown and live a quieter existence. Vinh’s sense of humor is thus demonstrative, once again, of a positive work attitudes pervasive in urban Vietnam.