The Collapse of the Armed Forces: Military Involvement

"The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at anytime in this century and possibly in the history of the United States.

By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous.” -Col. Robert D. Heinl Jr.

Col. Robert E. Heinl Jr.'s report "The Collapse of the Armed Forces" in the June, 1971 Armed Forces Journal revealed the extent of the U.S. military's institutional destruction during the Vietnam War. He showed a military riddled with desertion, crime, drug abuse, and racial tension caused by fighting an unpopular war with a lack of government and civilian support.

Many soldiers, like Boedtker, did not agree with American involvement in Vietnam or the objectives and tactics used. As opposition to the war mounted, the military played a key role in the antiwar movement. Members of the military who resisted the war effort did so risking punishment and retaliatory measures, yet nearly a quarter of all servicemen participated in the military antiwar movement as soldiers or veterans. This percentage equaled the peak proportion of student activists and exceeded activism among youth in general. As Heinl found in his report, 37% of soldiers engaged in dissent or disobedience with a third of these doing so repeatedly. The tactics used by the military were not only effective in protesting the war, but also profoundly impacted the structure of the military, which was reorganized in the years after the war to prevent a similar breakdown.

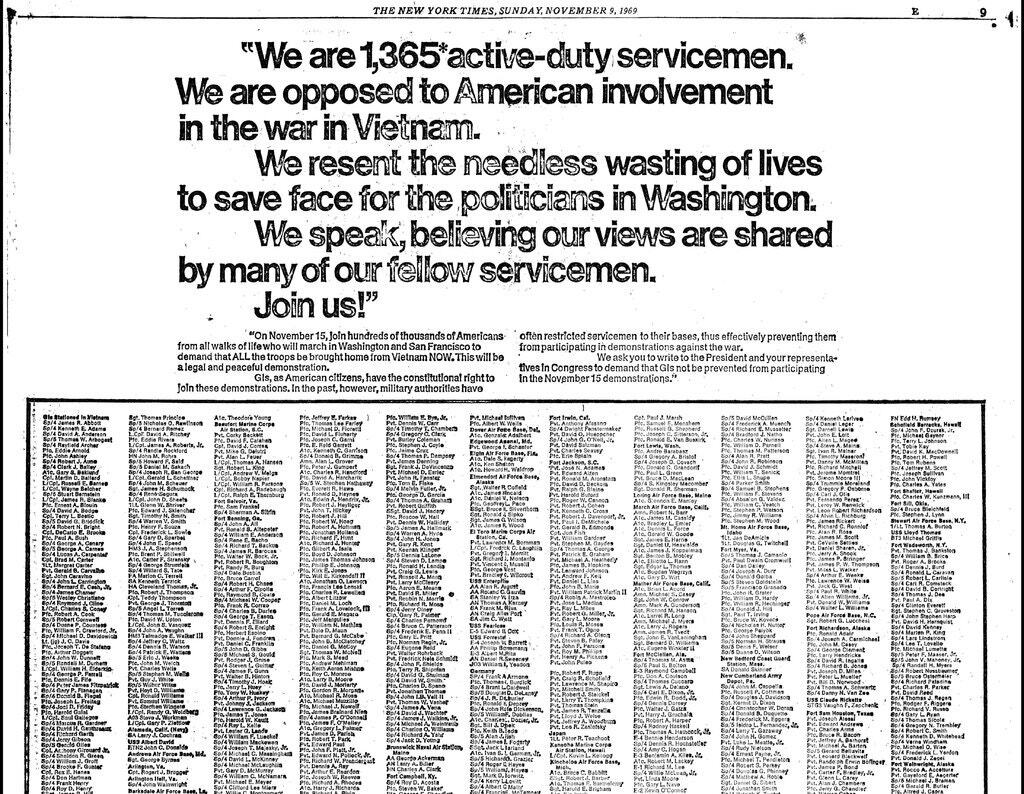

The G.I. Movement:

The G.I. Movement referrs to the organized, dissenting actions of servicemen during the war. It included acts of protest, demonstrations, and petitions (like the one shown on the left). One key feature of the G.I. Movement was its underground nature. G.I coffee houses emerged as spaces where dissenters could gather to decompress and escape military life, listen to music, and talk about politics. The first coffeehouses emerged in 1967 with the opening of UFO near Fort Jackson, SC and Oleo Strut near Fort Hood, TX. Coffeehouses were run by civilian antiwar activists at the edges of U.S. Bases.

Cofeehouses also served as places to read antiwar literature. Over the course of the war there were 300 individual antiwar newspapers run from bases and coffeehouses. These papers spread information about the antiwar movement and promoted resistance within the military. Heinl quotes two of these papers in his report that advise readers to rebel against their commanding officers. The Ft Lewis McChord Free Press writes, " In Vietnam, the Lifers, the Brass, are the true Enemy, not the enemy." The West Coast sheet has a similar sentiment, saying, "don't desert. Go to Vietnam and kill your commanding officer." Both of these papers capture the frustration and disconnect between officers and soldiers that disrupted the structure and effectiveness of the military.

Even in Germany, Boedtker found a division between the ranks of his unit. This lack of communication and division resulted in instances of combat refusal. Boedtker learned this from the Vietnam veterans he met during his service when they were pulled out of Vietnam and sent to finish their tours in Europe as part of Nixon's "Vietnamization" strategy. The veterans told him stories of troops refusing to fight, even with the threat of court martial. In his interview, Boedtker described the officers' lack of control:

"There wasn't much discipline at all. There was strength in numbers and the numbers were the infantrymen who didn't want to fight. There were very few people who thought this was the place to be, to go gung ho. And most of them could not wait for the tour to be over. And all they did was see their friends get killed over something that they really didn't have any heart in doing."

In some cases, these mutinies successfully cut short operations.

Fragging:

Fragging was a more violent form of insubordination in which enlisted men attempted to kill, or did kill, their commanding officers. The term stemmed from the use of fragmentation grenades in some of these incidents.

In his oral history, Douglas Shivers, who served with the U.S. Army from 1968-1971, describes a fragging incident. A member of his unit threw a thermal grenade onto the roof of the Non Commanding Officer's (NCO) barrack and the grenade melted through the structure's tin roof. The grenade landed next to the cook, though no one was killed in the attempt. This soldier also threw a gas grenade at the officers' barracks and the Enlisted Men's (EM) Club. The latter prompted outrage among the infantrymen as they were confused why he would attack his own. The soldier who committed these acts was never caught.

In Flower of the Dragon, Richard Boyle, a journalist who was in Vietnam during the war, describes another fragging incident. The medic of one unit, Doc Hampton, grew tired of the mistreatment and belittlement of the infantrymen by the Sergeant First Class Clarence Lowder. Much of this mistreatment had to do with the racial discrimination that Doc Hampton and other members of the unit felt as an African-Americans. Doc Hamptom shot Sfc. Lowder with his M-16 rifle, prompting a standoff between black soldiers protecting Doc and the "lifers" trying to retaliate. Doc killed himself before the situation could escalate, though he was described as a martyr by his friends in the unit.

Instances of fragging like these were not common. Heinl states that there were 109 cases in 1970, though the statistic may be deflated due to lack of reporting. Nevertheless, they demonstrate the complete decay of military order.

Racial Tension:

Issues of racial discrimination are inextricably linked to the military's opposition to the war. African American soldiers, bolstered by the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Power, fought against racial inequality within the military in addition to protesting the war itself. In 1970, Wallace Terry interviewed hundreds of veterans, both black and white, and found that the majority believed black people should not have to fight in the Vietnam War while facing discrimination at home. He also found that more black soldiers favored ending the war, believing the US had no justification in fighting, than white soldiers.

Black soldiers faced widespread discrimination in the military and were more likely to serve on the front line, were disciplined more harshly, and received more less-than-honorable discharges (data from GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War).

Boedtker describes the divisions that racial tension created within his unit, observing how different races tended to isolate themselves from one another. He remembers how he got into a fight for befriending an African American. He also highlights the fear that resulted, describing how he felt unsafe walking home late at night after several instances of being threatened.

Robert M. Watters discusses the racism he experienced as an African American fighting in Vietnam in his oral history. He talks about the omnipresence of racism going over on the plane and on the field as well as the jokes targeted at him. However, he found during combat, racial divisions became irrelevant, saying that "war has no skin." As people struggled for survival, they became more concerned with the quality of a person as a soldier rather than their race. As a result, he saw both black and white men overcome their preconceived notions of one another.