The American "Gift of Freedom" Discourse during the Vietnam War

Though Americans often consider the Vietnam War as a single war, the American Vietnam War was actually part of three consecutive wars in Vietnam, called the “Indochina Wars.” The First Indochina War was a colonial war of independence between the communist Viet Minh, based in North Vietnam, and the French colonial empire, based in South Vietnam. The war began in 1945 and lasted until 1954, when the French lost the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and consequently signed the Geneva Accords of 1954. The Geneva Accords split Vietnam into the North—the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam—and the South—the Republic of Vietnam, which the US supported. The US was not militarily involved in the First Indochina War, but according to its anti-communist views, the US condemned the Viet Minh and sent military aid and assistance to the French and the South Vietnamese.

The Second Indochina War, which Americans call the “Vietnam War,” began in the late 1950’s with a guerilla insurgency, called the National Liberation Front (or “Viet Cong”), in South Vietnam. The communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (secretly) backed the National Liberation Front. The US officially entered the war in 1964 following the Gulf of Tonkin incident. American intervention quickly escalated and became bogged down in the war, mainly from a lack of understanding of the war by the American military. Not only were the terrain and style of guerilla warfare unfamiliar, but the US simply did not grasp that for the Vietnamese, this war was both a war of independence and a civil war between the North and the South. The US entered as a champion of liberalism, fighting internationally to defeat communism, but to many of the Vietnamese, especially the communists, the US was simply another colonial empire seeking to prevent Vietnamese unification, independence, and freedom from external powers. The US withdrew its troops from Vietnam in 1973, and North Vietnam reunited the country on April 30, 1975. The Third Indochina War describes a series of prolonged conflicts, including the invasion of Cambodia to overthrow the Khmer Rouge and the consequent Sino-Vietnamese War between the Chinese, allied with the Khmer Rouge, and Vietnam.

As we will describe below, throughout American involvement in Vietnam, the US maintained an American salvation narrative. In the First Indochina War, the US acted as a benefactor of aid and assistance to those fighting against North Vietnam. Though the US was not militarily involved, as we will see below, the US began to establish the “gift of freedom” narrative. American intervention in the Vietnam War explicitly invoked the “gift of freedom” narrative, claiming to free the country from communist oppression.

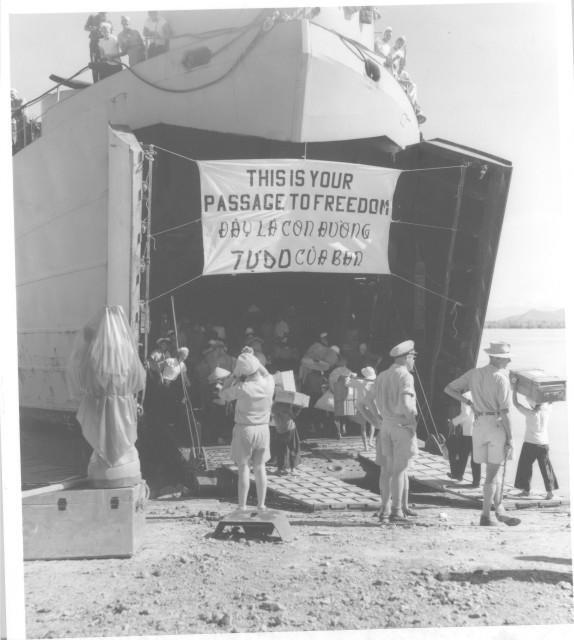

We can see the American salvation narrative in the picture above, which thanks Americans for their assistance and posits Vietnamese as thankful, hapless receivers of American aid. The picture was taken in 1954, meaning it was prior to any American presence in Vietnam besides aid. Nevertheless, the sign evokes a sense of thankfulness, which sets the stage for later indebtedness to the American "gift of freedom." Here, instead, the gift is aid and assistance.

The “Passage to Freedom Greeting Sign on LST-901 (USS Litchfield County)” is also taken prior to American military involvement in Vietnam, but it explicitly invokes the "gift of freedom" narrative. LST-901 is part of Operation Passage to Freedom, an American operation to help relocate Vietnamese refugees from North Vietnam to the South in 1954-1955. As part of the Geneva Accords of 1954, people were given a 300-day grace period to relocate according to their political affiliations. The US assisted the relocation efforts through the Operation Passage to Freedom, helping the North Vietnamese flee communist rule.

By placing the banner “This is Your Passage to Freedom” at the entrance to the US Naval ship LST-901, the US Navy suggests that it has the agency to grant the Vietnamese people freedom. The symbolism of the sign on the ship and its statement “This is Your Passage to Freedom” suggest that freedom is impossible in communist North Vietnam and, instead, the Vietnamese must board USS Litchfield County to find freedom elsewhere. This sign reinforces Nguyen’s argument that the “gift of freedom” establishes communist states as a place of fear and the US as the vehicle for freedom.

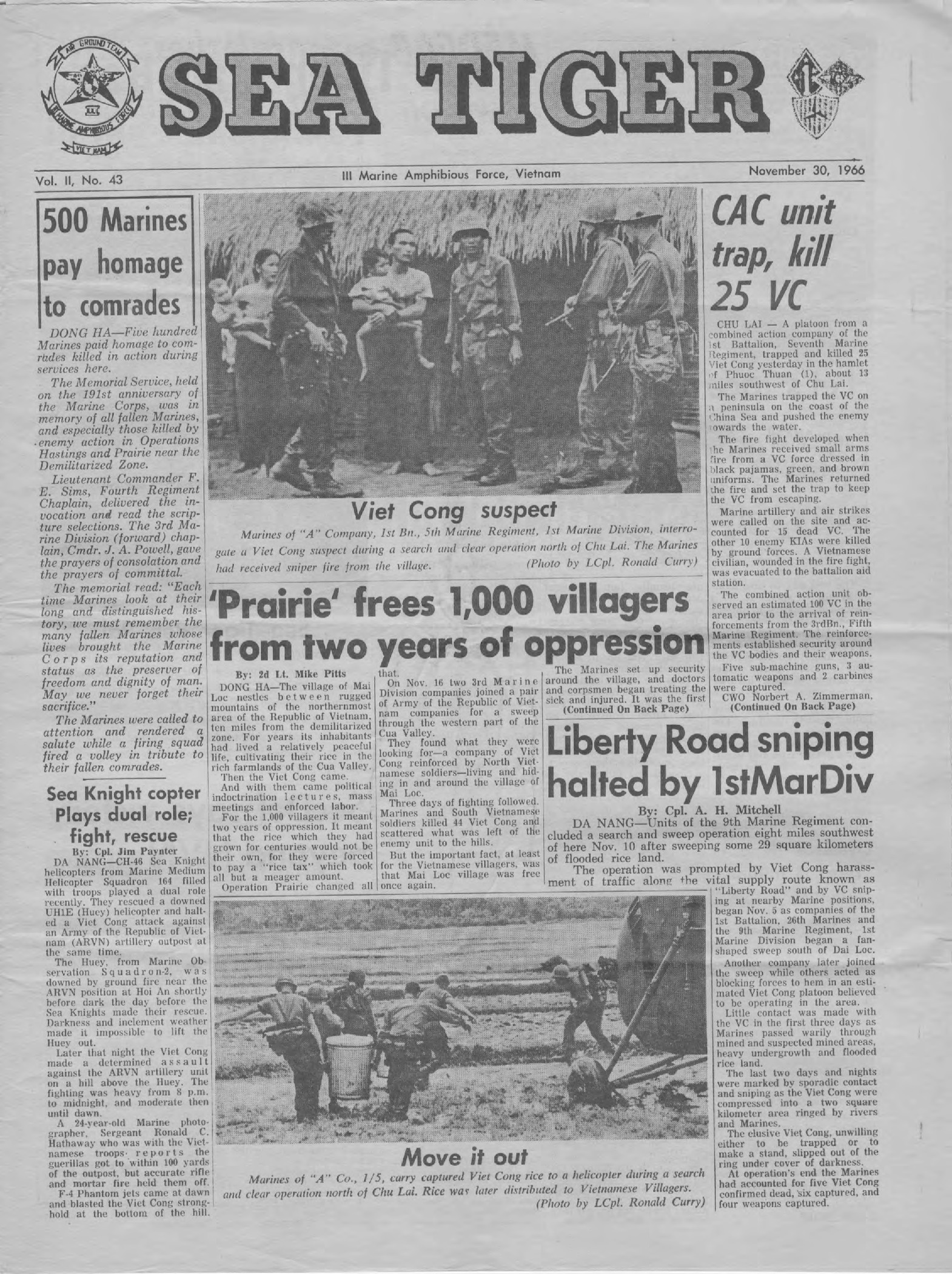

The "gift of freedom" narrative is evident in the newspaper to the right, which is the November 30, 1966, edition of the III Marine Amphibious Force’s weekly newspaper, the Sea Tiger. The US entered the Vietnam War under the presumption of freeing the Vietnamese people from communist rule, an attitude exemplified in the newspaper. The headliner “‘[Operation] Prairie’ frees 1,000 villagers from two years of oppression” uses the language of the American savior, portraying the US as the protector of freedom. The tone in the newspaper article, specifically that the villagers were unable to free themselves without the Marine’s Operation Prairie, implies that the Vietnamese need the US for freedom, thus positing the Vietnamese as beholden and inferior to American forces. The article supports Nguyen’s thesis that the American claim to the “gift of freedom” is an empire and racial hierarchy making tool.

The included artifacts demonstrate that the US invoked the “gift of freedom” narrative during the Vietnam War to justify its intervention. As evident in the “Passage to Freedom Greeting Sign on LST-901 (USS Litchfield County)” and “Greeting from Refugees (September 1954),” even prior to American involvement, the US had already established itself as a benefactor gifting freedom to the Vietnamese people. The newspaper included describes American attitudes towards military intervention, characterizing the US as actively freeing the Vietnamese. The American mindset during the war sets the stage for a similar post-war narrative that maintains the hierarchical relationship between the US as the giver of freedom and the Vietnamese as grateful recipients.

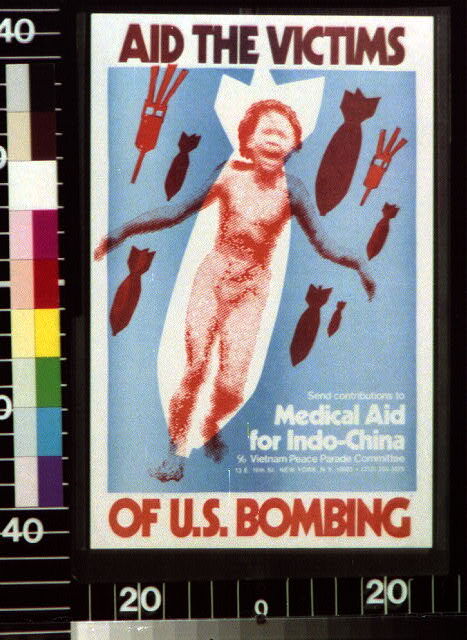

During the war, anti-war protests contested the American salvation narrative and American “gift of freedom” rhetoric. The poster to the right is an example of the anti-war movement’s efforts to highlight American atrocities in the war, including bombings that killed and maimed children. The anti-war protests counter American assertions of gifting freedom to grateful Vietnamese citizens by depicting the war as an imperial, violent endeavor.