The Passage of the US Amerasian Homecoming Act

Beginning in the 1980s, American public consciousness of Amerasians increased. In Vietnam, Amerasians served as a reminder of the Vietnam War and American intervention. In the US, Amerasians reminded the American public of American military failure and withdrawal from Vietnam. In order to repaint American failure as the American salvation narrative, the US passed immigration acts helping Amerasian children immigrate to the US. By bringing Amerasians to the US, the US claimed to save Amerasian children from marginalization and communism in Vietnam. American media accordingly focused on and dramatized the abandonment of Amerasian children. On this page, we will examine the Amerasian Immigration Act of 1982 and the Amerasian Homecoming Act (1988) and how the two laws use the “gift of freedom” rhetoric to perpetuate the American salvation narrative.

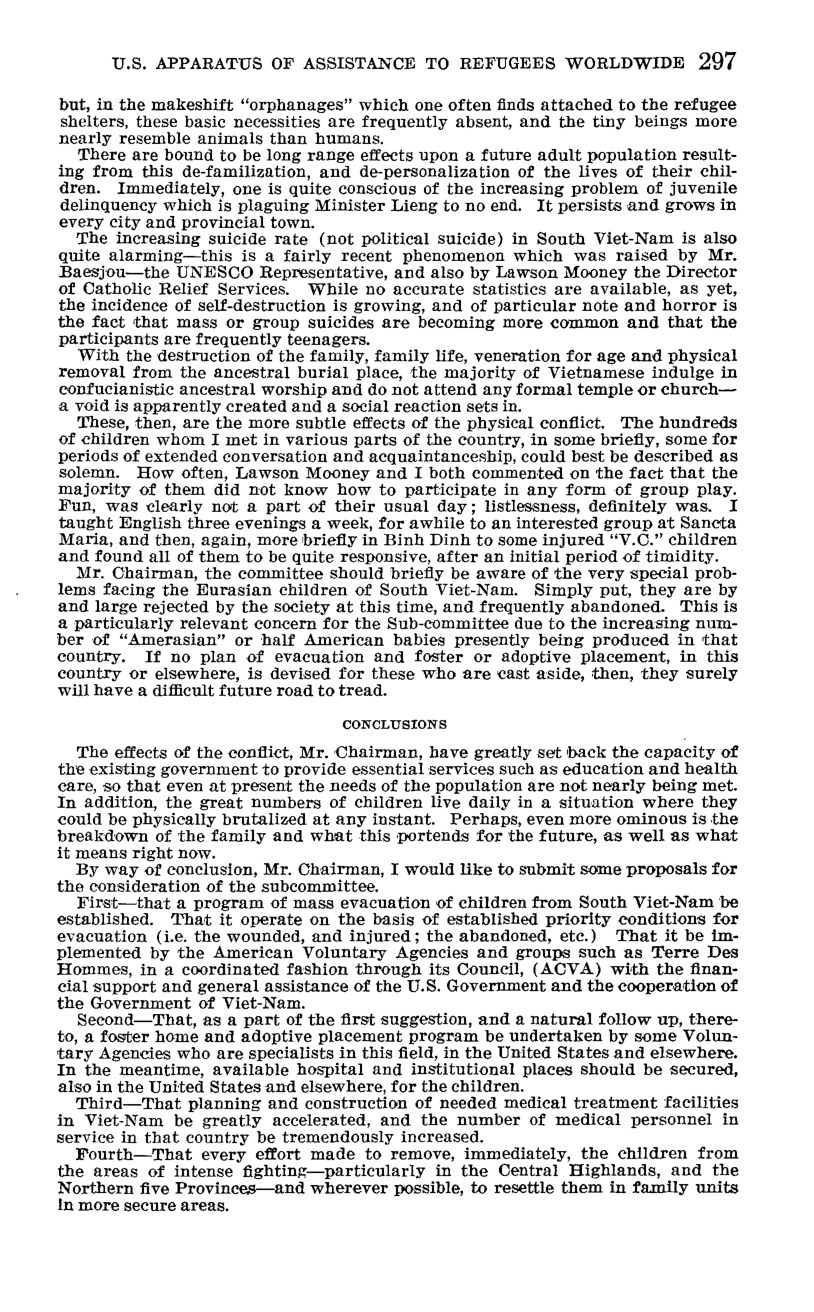

In the document "Record of Debates in US Apparatus of Assistance to Refugees Throughout the World (1966)," we see the first written mention of Amerasians from the Vietnam War. We should note that this short paragraph, reproduced above, is the only mention of Amerasians in the entire document and that the speaker states “the committee should briefly be aware” (emphasis added), indicating that the predicament of Amerasians is a relatively insignificant topic. Although the paragraph accurately describes the predicament of Amerasian chilren, noting that Amerasians are "by and large rejected by the society at this time and frequently abandoned," no action is taken to protect Amerasians following this discussion.

The Committee’s document accurately suggests that the predicament of Amerasians will be a future problem for the US, stating that the US should institute a “plan of evacuation and foster or adoptive placement.” Despite the timing of the 1966 record above, no program was created until the 1980s, after the US had withdrawn from the war and had to deal with the repercussions of losing a war. Congress only began protecting Amerasians in the 1980s when Amerasians' stories became widely published.

Amerasian Immmigration Act (1982)

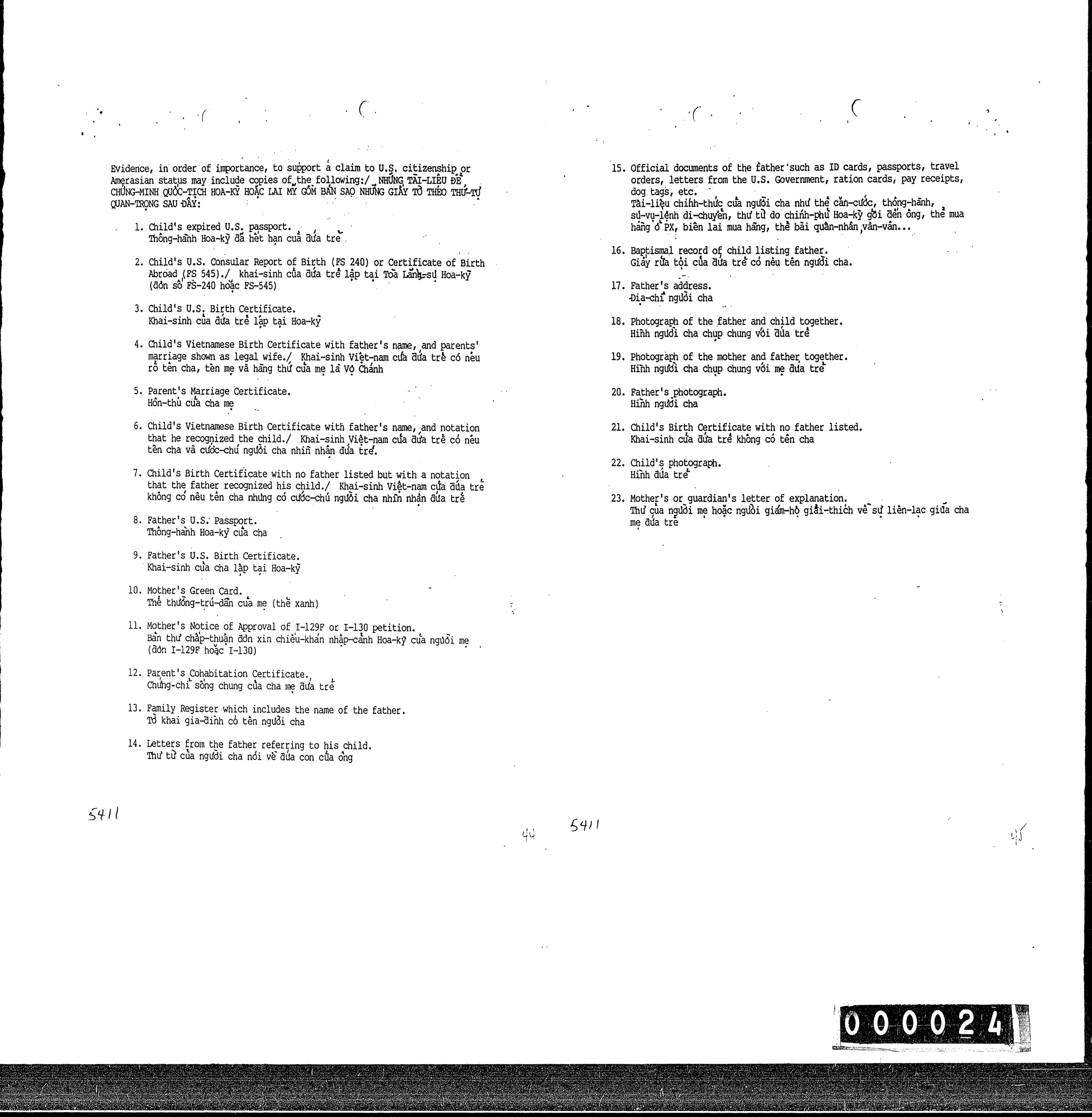

The Amerasian Immigration Act of 1982 was an amendment to the Immigration and Nationality Act and allowed Amerasians to immigrate to the US. The requirements to prove Amerasian identity were stringent, as evident in the “Amerasian Review Checklist” reproduced to the left. As Sabrina Thomas discusses in the article “Blood Politics: Reproducing the Children of ‘Others’ in the 1982 Amerasian Immigration Act,” the 1982 Amerasian Immigration Act focuses on blood identity, meaning the identity of both parents. According to the Amerasian Act of 1982, Amerasians were only considered “Amerasian” if they could prove they had a Vietnamese mother and an American father. However, as Caroline Valverde discusses in her article, mothers often destroyed records of their relationships and their children’s identity to safeguard them from discrimination. Thus, proving paternal identity was nearly impossible. Many Amerasians were consequently unable to immigrate to the US under the Amerasian Act of 1982.

The Amerasian Act of 1982 did not offer full citizenship to Amerasians even though the Immigration and Nationality Act extends citizenship to children born to an American parent outside of the US. As discussed in Thomas’ article, this refusal to offer citizenship stems from racism. Thomas notes that the US has a history of racialization and marginalization of mixed-race peoples and a history of Orientalism, producing an inability to reconcile Caucasian features with Asian descent. In American history, mixed-race peoples such as mestizos were denied citizenship or put in lower racial castes than their white peers because mixed-race peoples were not considered white enough. Similarly, Americans could not accept Amerasians as citizens despite their American bloodline because their blood identity was part Asian. The US has a history of racism against Asians, evident in the Chinese Exclusion Acts and Japanese internment camps. The combination of racism against Asians and against mixed-race peoples resulted in the Amerasian Immigration Act of 1982 only assisting Amerasian immigration but not offering citizenship.

The Amerasian Immigration Act reflects the American savior complex in its claim to saving Amerasians from Vietnam without adequately assisting Amerasians. In addition to high standards for Amerasian identity and not offering citizenship, the Amerasian Immigration Act separated Amerasian children from their families by only offering to help Amerasians immigrate. This narrow view of only helping Amerasian children themselves immigrate reflects an American savior complex that assumes only helping the child will fix the problem. However, many Amerasians were still children who needed their families and could not immigrate without them. Consequently, the Amerasian Immigration Act was not an appealing means to leave Vietnam. American failure to grasp the nuances of the Amerasian predicament suggests that the Amerasian Immigration Act was not designed for the protection of Amerasian children.

The Amerasian Homecoming Act (1988)

Public condemnation of the treatment of Amerasians spurred the Amerasian Homecoming Act. In 1987, Audrey Tiernan, a photographer for Newsday, photographed Le Van Minh, an orphaned Amerasian with polio. The photo of Le Van Minh, reproduced to the right, inspired high schoolers at Huntington High School in New York to ask their representative, Robert “Bob” Mrazek, to protect Amerasian children. Following the publication of Tiernan’s photo, journalist Irene Virag at Newsday and other news sources began extensive coverage of Amerasians, popularizing and dramatizing their experiences. This public pressure and coverage led Representative Bob Mrazek to push the Amerasian Homecoming Act through Congress.

The Amerasian Homecoming allowed entire families to immigrate with their Amerasian child, preserving family unity and encouraging immigration. This difference signifies an improvement in American understanding of Amerasian predicaments. The Amerasian Homecoming Act rectified blood identity problem presented in the 1982 Amerasian Immigration Act by instead making the identity physical. The Amerasian Homecoming Act used racist, unreliable physical tests and standards to determine the Amerasian identity instead of requiring paternal verification. The expedited immigration process was ultimately ended because non-Amerasian Vietnamese citizens used American racism to pass the physical test and immigrate to the US and because some Vietnamese families paid Amerasian children to claim to be part of their family to immigrate.

The “gift of freedom” narrative is reproduced in the Amerasian Homecoming Act. As discussed above, the Amerasian Homecoming Act was passed largely due to sustained coverage of Amerasians in Vietnam. When Le Van Minh was granted a visa to the US, Huntington High School in New York, the high school responsible for pressuring Representative Bob Mrazek to sponsor the Amerasian Homecoming Act, hosted a “Le Van Minh Day.” At the celebration, as written by Irene Virag in the article “Le Van Minh’s Friends Celebrate,” Mrazek addressed the students the following: “‘Very soon you will all have a chance to meet a young man whose life you’ve saved… You should be proud. Your high school is responsible for bringing Le out of a life of misery to a new life in America.’” Mrazek’s statement reflects “the gift of freedom” sentiments, namely that these American students gifted Le Van Minh freedom and are bringing him “out of a life of misery.” Specifically, they have “saved” Le Van Minh’s life, indicating that the Americans are solely responsible for gifting opportunity and life. The article reinforces the “gift of freedom” narrative by reproducing narratives of helpless refugees relying on American saviors.