"Children of the Dust": Amerasian Experiences in Vietnam

Many American soldiers fathered children with Vietnamese women during the American involvement in the Vietnam War. The US government became concerned about the fate of these Amerasian children in official records as early as 1966, but no legal action was taken until the 1980s. Focus on Amerasians grew after American withdrawal from Vietnam, mainly because Amerasians served as a physical reminder of American failure and abandonment. This focus ultimately produced immigration laws that expedited the immigration of Amerasian children and, eventually, their families. This page provides background information on the Amerasian experience in Vietnam.

Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde’s “From Dust to Gold: The Vietnamese Amerasian Experience” describes the rejection Amerasians face referenced in the quote above. Vietnamese society rejected Amerasians for not having a father because Vietnamese cultural norms believe that “‘a child without a father is like a house without a roof.’” Most Amerasian children never knew their father because, though some unions between American soldiers and Vietnamese women were lasting relationships, many were short-lasting and ended when the soldier left Vietnam. Valverde writes that “Amerasians abandoned in Vietnam endured Communist persecution because of their mothers’ involvement with Americans, prejudice because of their racial makeup in a homogenous society, and classism because they were fatherless in a patriarchal society.” Because of this persecution, many mothers destroyed all evidence of their relationship with American men, making it even more difficult for Amerasian children to locate their fathers. In addition to rejection, Amerasians were especially vulnerable because “education [was] still regarded as a luxury,” so Amerasians were often instructed to leave school. Accordingly, many Amerasians became homeless and went to cities to earn a living. In response, Amerasians were labelled “bui doi (dust of life), which is equated with homeless or rebellious individuals.”

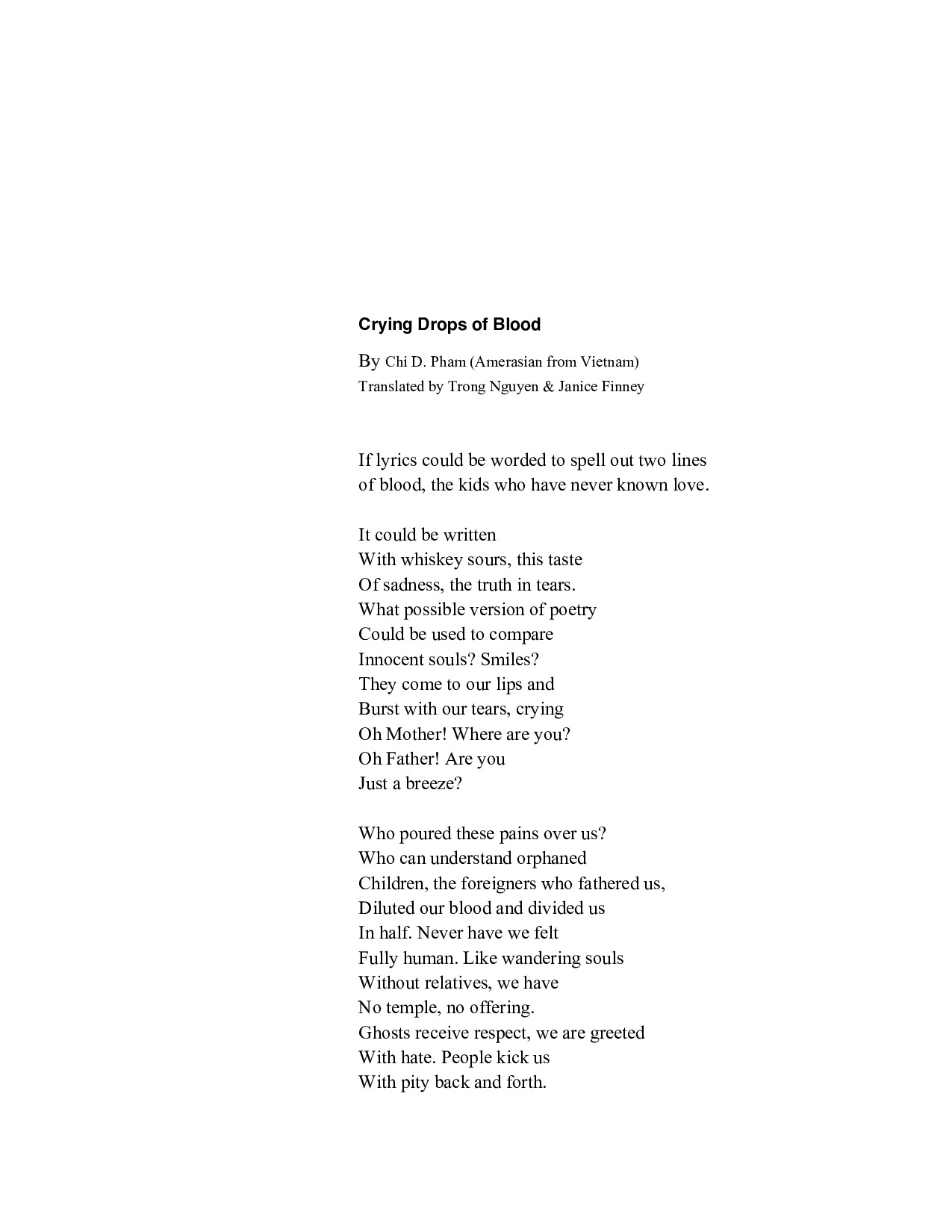

Chi D. Pham’s poem “Crying Drops of Blood” illustrates the abandonment of Amerasians. As Pham writes, “Never have we felt / Fully human. Like wandering souls / Without relatives, we have / No temple, no offering.” These lines describe the reality of being bui doi (the dust of life): Amerasian children felt unrooted and unwanted in Vietnam because they were marginalized for never knowing their fathers in a patriarchal society and for serving as a physical reminder of the Vietnam War. The final sentence “People kick us / With pity back and forth” references the complicated plight of Amerasians as an object of American pity and Vietnamese rejection. Although Americans claim to welcome Amerasians “home” in legislation like the Amerasian Homecoming Act, considering Amerasians as an object of pity precluded recognizing their full humanity. Accordingly, no society ever understood Amerasians as “fully human,” establishing a constant sense of marginalization and abandonment.

Though Amerasians experienced the discrimination described above starting from birth, the US did not take legal responsibility for Amerasians until the 1980s when Amerasians' stories became widely published. As Valverde discusses, the American media stereotyped Amerasians as “helpless children searching for their American fathers.” Though this stereotype dramatized Amerasians' predicament and established an American salvation narrative in which Amerasians needed American aid, this degrading stereotype nevertheless fostered the public support and concern that pushed the Amerasian Homecoming Act through Congress. We will explore this stereotype and the passage of the Amerasian Homecoming Act on the following page.