Diverse motives: Why volunteer in Vietnam?

When asked why she volunteered to serve in Vietnam, Gayle’s response seems deceivingly simple: “I wanted to bring back people that I didn’t think belong there.” That statement from our February 2020 interview is almost identical to her testimony in Al Santoli’s 1981 oral history collection Everything We Had. Gayle’s chapter, “The Nurse with Round Eyes,” begins with: “I wanted to go to Vietnam to help people who didn’t belong there.”

Gayle objected to the Vietnam War. “It's not like World War II; it wasn't like Korea," she explained. "I mean, this was a country in a civil war. And what the heck are we doing over there?”. Despite her assertion that “I knew I was going to hate the Army,” she decided to enlist.

Gayle signed up to save the boys being shipped to Vietnam. In her role as a nurse, she could help usher home injured soldiers. “Get outta here, go home!” was her unspoken message to the men she healed.

Out of five thousand women deployed to Vietnam during the war, only nine were killed, according to Kara Dixon Vuic in her book Officer, Nurse, Woman. Of those, seven died in plane or helicopter crashed; two died of illness. Average Americans and soldiers alike assumed that wherever the women were in Vietnam -- despite being stationed in a combat zone -- that the area was safe. Military leaders projected this illusion of calm, if only to assuage the fears of nervous parents whose girl-next-door daughters were a world away from the safety of Main Street, U.S.A.

Gayle, however, was prepared to die. Before leaving for Vietnam, she saw the plot in which she would be buried if killed in action. Gayle was militant about her job as a protector and savior of individual soldiers in Vietnam. “They,” – the soldiers – “would do anything for each other, and they would do anything for me. And I would do anything for them,” she said.

“The policy was [if] somebody knocks on the door after night, you shoot first and ask questions later … I was willing to do that for my patients: kill anybody. I had to save my patients. [I’d do it] in a heartbeat -- in less than a heartbeat.”

It’s a nurse’s job to preserve life. Gayle took that mission literally: she would defend, to the best of her ability, every single young man that came into the 3rd Surgical Hospital in Binh Thuy.

*

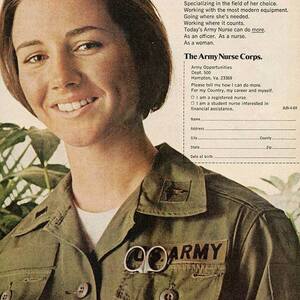

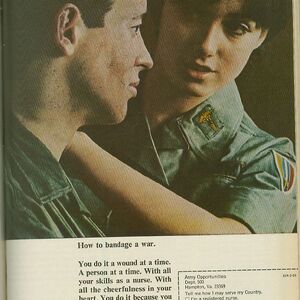

The U.S. Military, in advertisements posted in women’s and nursing magazines, depicted life in the military as glamorous, patriotic, and exciting. Women could maintain their femininity – after all, nurses were expected to wear heels and lipstick in Vietnam – while achieving the respect and leadership normally afforded to men through the nurses' rank of Officer.

Mass media echoed appeals to femininity. Judy Klemesrud at The New York Times wrote that women were lured by “travel, adventure, snappy uniforms, and an abundance of men.” Klemesrud noted that women could adopt or raise children during their service in Vietnam. And while they might face cultural taboos, the girls volunteering for Vietnam will not encounter abundant Lesbianism or “lose their moral values.”

Advertisements and articles provide one window through which to evaluate why women chose to serve in Vietnam. Oral history provides another. No oral history I reviewed cited "an abundance of men" (even in jest) as a reason to enlist in the U.S. Military. Some cited purely financial reasons for serving ("It wasn't duty or honor," said Mary Messerschmidt in Vuic's Officer, Nurse, Woman. Rather, "they were paying for me to go to school.") However, most women's rationale was nuanced. The most common reasons that a woman might volunteer for a Vietnam deployment as a nurse are as follows:

To seek adventure: Some women volunteered for Vietnam seeking a sense of adventure. Elizabeth Norman in her book Women at War: the Story of Fifty Military Nurses who Served in Vietnam, notes that the vast majority of women in the Army Nurse Corps were white Catholics or Protestants from working or middle class families. Like Gayle, many of their fathers served in World War II. Vietnam provided an opportunity to leave their hometowns and see the world. "I always wanted to see the Orient and get out of Florida!" said one nurse in who Norman interviewed. Some volunteered for Vietnam as idealists: “On a whim, my friend and I put in our papers to go to Vietnam. That's about all the thought I gave it!", said another nurse who Norman interviewed.

To avoid the confines of American femininity: At age twenty-two or twenty-three, the countdown to marriage was on the minds of many of the women who volunteered for the Army Nurse Corps. For some women, expectations of what it meant to be a good woman – to marry, to raise children, and work in a 'woman’s job' – were stifling. "Everyone else in nursing school was going home to get married. I was not going to do that. I did not want to come home to Somerville, New Jersey, because I was afraid that in 35 years I would still be there," said one nurse in Women at War. Sharon Stanley-Alden in Vuic's Officer, Nurse, Woman observed that "Women were nurses, or secretaries, or teachers. And that's pretty much what we did. Or moms. Stay-at-home moms. And I didn't see myself getting married right away and having children right away." In Vietnam, one could pursue the beginning of career in nursing an accelerated level with the respected title of Officer.

To fulfill a patriotic duty: A duty to serve one’s country wasn’t a duty that was confined to men, some women noted. Judy Hartline Elbring in Woman, Officer, Nurse wrote that "The [war] stories that I had heard my father tell made it sound like it was very exciting. It was a chance to contribute, it was very patriotic, it was an American thing to do, and it was something that I could do now." Nancy Margaret Christ, also quoted in Vuic's work, aligned her service in Vietnam with a duty to serve: "As a member of the military my job was to follow the commend of my Commander in Chief -- the President of the United States." For these women, serving in the military was respected at home and in the local community. Nancy Randolph told Vuic that "If you were in the Army and there was something going on, you had an obligation to go." Given the military background of many women who chose to serve in Vietnam, it's no surprise that patriotism was a guiding force.

To ally with brothers-in-arms: This motive for service most closely resembles Gayle’s reasoning. Women with brothers and those with close male friends witnessed their male counterparts face the moral question of how to respond to the draft. Women recognized that their gender -- once again -- precluded them from opportunity. The opportunity to serve was unlike other professional opportunities; this one had a morale valance that got personal as the death toll in Vietnam climbed. While their gender barred them from being subject to the draft, it did not bar women from moral and ethical questions about who is called to serve. “How could I say, 'Oh no, not me,' when men my age were going?” recalled an anonymous army nurse in Norman's Women at War. She continued with "I really felt, 'How come not me?'” Lily Lee Adams, quoted in Vuic, also recognized the gender disparity. Rather than feel lucky that she was naturally exempt from the draft, "I felt very guilty that the guys had to deal with these decisions--major decisions in their lives--and that girls didn't." For others like Donna B. Cull Peck, also quoted in Vuic, the choice was between cowardice and courage: "The only reason I can go with a clear conscious is that half of these guys are like us: obedient. They wouldn’t have thought of saying no, and they were getting wounded and probably didn't want to be either. There were so many young boys that wouldn't have thought of saying 'no'. They had the courage to do it, and I'm glad I did too."

As they decided to go to war, women may have identified with multiple of the above categories. I found only one example of an Army nurse who, like Gayle, was verbally anti-war but found more use in service than in protest. Peggy Mikelonis, when interviewed for the Texas Tech Vietnam Archive, said, “I didn’t support the war, but I wasn’t going to be one of the protestors, so I wanted to go and help take care of those who were over there and I saw it as my opportunity.” For many others, the cognitive dissonance between professing anti-war rhetoric but contributing to war-making abroad was too great a gap to mentally and emotionally bridge.

*