Quotidian trauma: What was so traumatic about caregiving in Vietnam?

“It's like it happened yesterday. I see it. I can see it all, right in my head, I can see everything,” Gayle said, in reference to the death of Spec. John Henry Lopochonsky. An abridged account of Gayle’s memory of John, detailed in her oral history, is copied below:

“It was July 17th, 1971. And he [Lopochonsky] was in a helicopter [that] got shot down … And he's burned [on] 100% of his body. And the bones are sticking out of his right leg.

And he came in about maybe two o'clock in the afternoon. I came on duty at seven [o’clock].

And the other nurses were saying, ‘He's got a track scholarship to Penn State [University, PA].’ …

Most of my patients know when they're going to die, they know it. They know even before they get hit over there [in Vietnam]. [They say], ‘It didn't feel right, may not come back from this one.’ And that happened.

So I went over to him and I said, ‘I hear you got a scholarship to Penn State.’

He says, ‘Yeah, but I don't think I'm gonna make it. I'm not gonna make it out of this one.’

I said, 'You're right.' I said, ‘Do you want me to write a letter to your parents or [you] got a girlfriend or something?’

And he says, ‘No.’

And those were the last words he spoke.

And I said, ‘Well, you're not going to be alone.’

[I] gave him some morphine, as much as I could, and whispered in his ears. Because -- usually -- I hold hands, but he had four hands. This one [creates fist] was meat. And this one [with other hand, cups hand below fist] was skin of his hand, all in one piece. It was like this [demonstrates how the skin was loosely hanging off the bottom of what was left of his hand]. Of course, you can't recognize him -- 100% burns.

It was hopeless, a hopeless situation. He knew it.

So, I had to put him in a bag and send him home to his mother.

That was hard. I was upset.

And then, there was a supervisor, a nursing supervisor who was in the ER. And he came in and he gave me a Coke. I thought that was the most important thing in the world to me. That he cared enough -- he knew how upset I was that this guy died, and he gave me a Coke.

I never forgot that."

Almost every nurse whose testimony I read remembered at least one John Lopochonsky: that one soldier whose death still haunts them. Elizabeth Norman, in reviewing the experiences of fifty Army nurses she profiled, wrote that “Only one woman [out of fifty] said she did not remember any of her charges [personally]. The other women ... cried as they remembered special patients. ... Some women knew the names, ages, types of wounds, prognoses, even the sound of their patients' voices. Others simple recalled a look, a statement, or a gesture.”

Knowing John’s name humanized the dying burn victim that has been seared into Gayle's memory. It’s also allowed her to find his surviving family members and share that someone -- she -- was with John when he died. John may have died in vain, but he did not die alone. Reaching out to John's siblings seemed to have provided Gayle with a sense of closure. For years, Gayle shouldered the weight of John alone; now, people who cared deeply about John could share in the pain and catharsis of knowing that he died in care.

Others nurses, however, were glad to remain ignorant of their patients’ names and other identifiable information. The weight of knowing – of comprehending the full humanity patients who died in horrific ways -- was too great to bear.

“A nineteen-year-old came in with abdominal wounds and an undetected hole in the back of his head,” a nurse in Norman’s study said. “We'd pump blood into him and it would pour out the back. He was fully conscious. It was late at night. As I get him ready to go to the OR, he's talking to me, saying, ‘My name is ...’ -- thank God I won't remember it -- ‘I'm from ... I have a little sister .... please .... my parents.’ He knew he was going to die and he made me promise to write to his parents, which I did. ... It was tough, it was tough."

These women describe their experiences as “tough” and “upsetting.” Nurses may minimize their trauma for the sake of polite conversation with the listener. They may also may do so to prevent themselves from slipping into overwhelming emotion associated with their memory. Whatever their reason for downplaying these stories, it’s clear to the casual reader that nurses in Vietnam experienced serious trauma.

The trauma of an Army nurse was unique: trauma was frequent, had both an emotional and physical element, and was necessarily repressed to perform the demanding role of nurse.

First, trauma was constant: Nurses would only see soldiers when something was wrong. Sometimes, that “something” was as mild as a broken finger. Other times, nurses would assess patients arriving DOA (Dead On Arrival), with severe bullet wounds or with burning, rotting flesh. Daily exposure to carnage wore on nurses over time. In Heikkila’s Sisterhood of War, one nurse reflected that her male counterparts 'weren't in fights every day. They'd be on patrol for sometimes even weeks before they'd have a firefight. And so there were one or two things in their year that they could identify [as traumatic]. Every day was a trauma for me.” Drinking was common among nurses and doctors. However, getting drunk wasn’t an option: just as soldiers anticipated an ambush, nurses and doctors anticipated the next injury that would require their clear-minded attention.

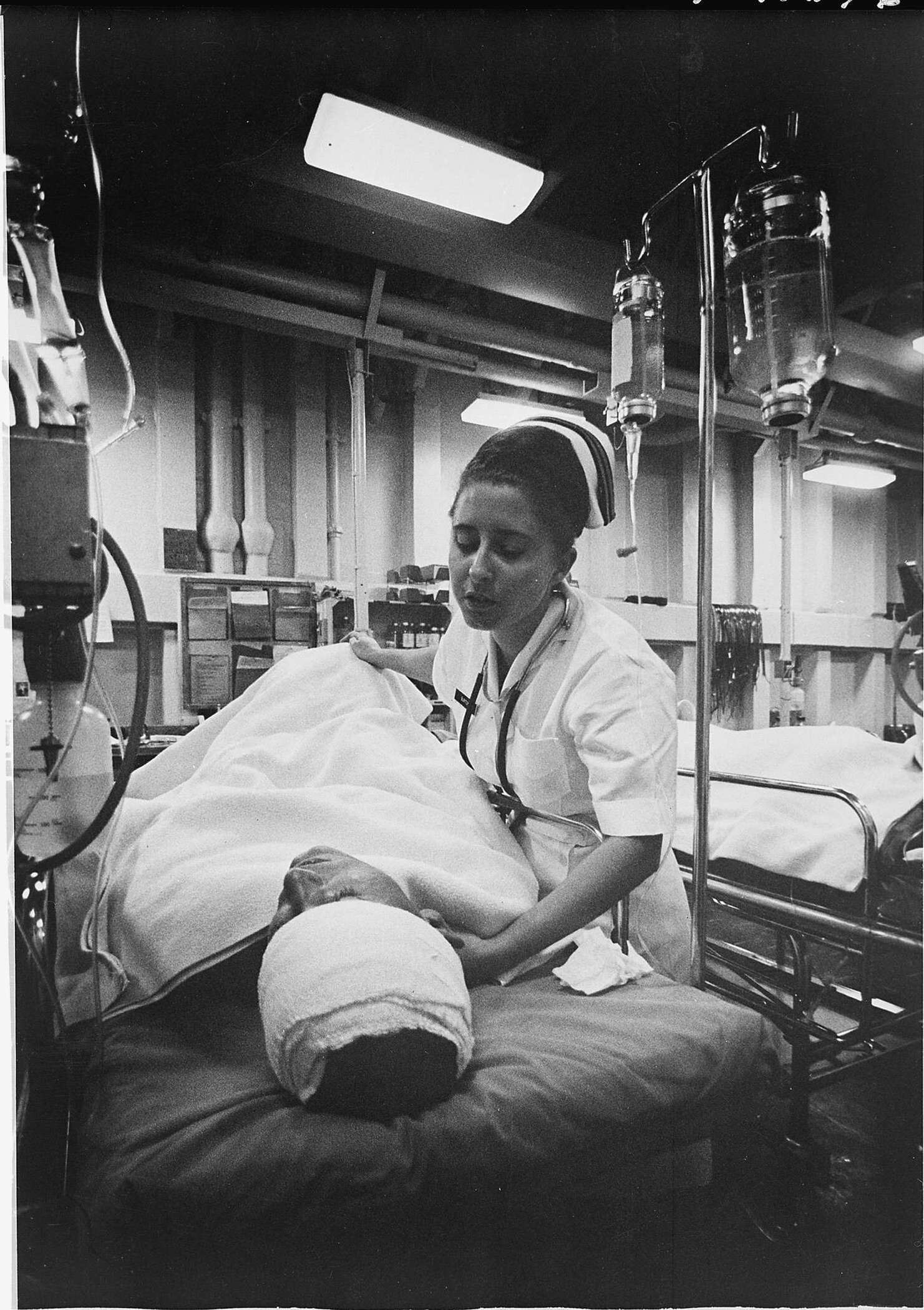

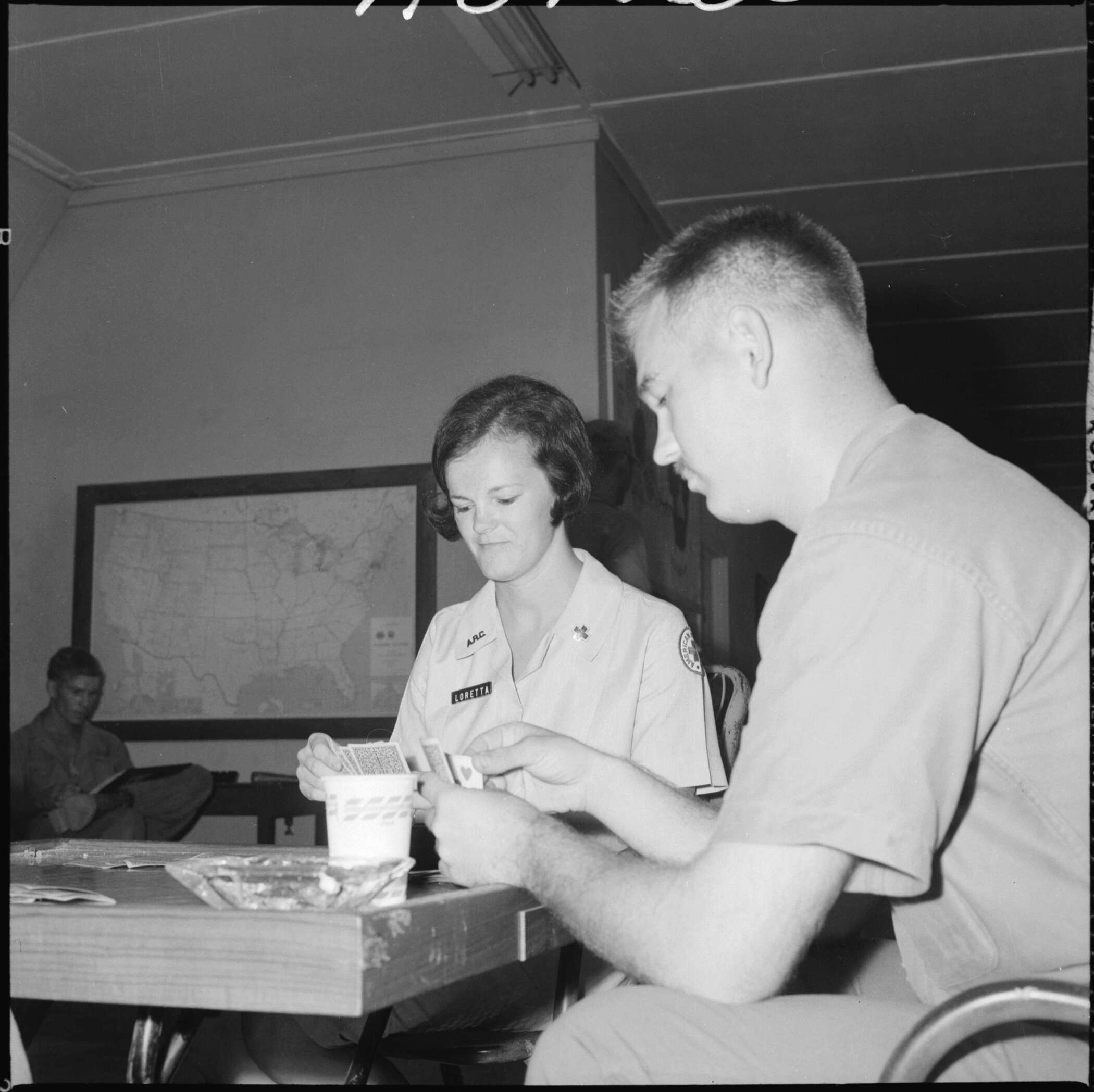

Second, given their womanhood, it was expected that nurses shoulder their patients’ emotional trauma, as well as heal their physical wounds. The women in the Army Nurse Corps donned not only the hat of nurse -- setting up IVs, clamping bleeders, and triaging patient needs – but also played the role of the comforting American woman. They were mother, girlfriend, and sister in one. Bandaging a soldier who lost his leg could be traumatic; so, too was offering a hug after he broke the news to his mother on a phone call that her son was disabled for life. "When the end was near," a nurse said in her conversation with Elizabeth Norman, "I would just stand near them. I felt that his mother would feel better knowing that someone was standing with her son when he died.” Nurses bore the burden of bearing witness. They wrote letters home to parents and, in doing so, shouldered the responsibility of protecting loved ones at home from full, graphic knowledge about how their sons died. Gayle said it was absolutely necessary to compartmentalize: “You learn when you leave the hospital [to] leave it behind or you're never going to survive. So when you walk out the door, you push it aside.” Her next phrase is all the more startling: “And for some things, it's hard. Like when John was burned -- I'm sure you haven't ever smelled a burn patient, but it gets in you. You wash your hair. You blow your nose. You brush your teeth. You take a shower. The smell of burned flesh is still in you.” Despite their best efforts, nurses couldn’t or wouldn’t fully compartmentalize.

Finally, the trauma of Army nurses was repressed. Nurses felt a responsibility to put on a strong, friendly, and comforting face around their patients. If these men were the ones who suffered the injury, who were the nurses to cry? In Women at War, Norman notes that the “most common way in which the nurses reacted to the men's selflessness was to insulate themselves, to build up a shield that allowed them to work.” Emotional protection was chipped away by particularly graphic images or by empathizing with patients as people. Women were torn between two competing needs: a need for self-preservation drove many to distance themselves from their patients, yet a need for empathic nursing drove them to provide emotional comfort in a soldier’s final or most fearful moments. The irony worsens: Real-time repression allowed women to complete the role as nurse in Vietnam, but it's their repression that would make it so difficult to unpack trauma, years later. “You don't process this stuff,” Gayle said. “You just try and hang on … [You] keep on going forward and say, ‘Okay, I hope I make. Hope I make it.”

*