"Corpsman Up"

Corpsmen worked alongside Marines with a specific goal in mind: to save as many men as possible. This unofficial mantra was something those young men took to heart. Ronald Glasser, a doctor in a military hospital in Camp Zama, Japan, commented on the attitude of Corpsmen in September 1968 (excerpt from this book): “growing up in a hypocritical adult world and placed in the middle of a war that even the dullest of them find difficult to believe in, much less die for, very young and vulnerable, they are suddenly tapped not for their selfishness or greed but for their grace and wisdom, not for their brutality but for their love in concern.” More than describing the horrific injuries, Corpsmen noted their compassion and ability to remain calm while exhibiting bravery in order to complete the job at hand; saving men. Furthermore, they were proud of themselves for doing so.

During Jack Cassidy’s interview, he elaborated on the importance of taking care of his fellow Marines. While Marines held true to their riflemen roots, Jack knew his job was different: “they [the Navy] got me to patch people up. So that’s what I should concentrate on. And that’s what I did.” While in the Arizona territory near An Hoa, Jack and his fellow Marines went on a night patrol through a rice patty. One Marine triggered a booby trap. The ensuing explosion resulted in the Marine losing both of his legs. When Jack's men called him into action, he had to navigate additional booby traps on the rice patty to get to the casualty. By using toilet paper to mark and avoid other trip wires, Jack made his way to the casualty and stabilized him by starting an “IV in the dark.” On the whole event, Jack recounted: “I saved him…I was very proud.” The young Marine went on to name his child after Jack.

Delta Company 1/26 Corpsman Bob Cahill remarked: “Whenever you hear Corpsman up, you go”. Cahill performed medical feats he was proud of as well, for example, using an empty syringe to do a makeshift tracheotomy on a Marine wounded in the neck during one of his first serious firefights. On that day, which Cahill described as one of the “most horrible days in Vietnam,” 10 men from his company perished. Despite horrific conditions, the loss of comrades, and having to endure a two to three-hour firefight, Cahill remained focused on the task at hand, resulting in his saving of the life of the Marine with the makeshift tracheotomy. Corpsman Cahill remained committed to the casualty, even riding with him on the Medevac helicopter after the conclusion of the firefight. Cahill's pride in his ability to provide quality medical care extended beyond just caring for his soldiers. In his narrative, Cahill also described times that he cared for civilians. When moving through various villages, he treated shrapnel wounds and malaria. Despite not being immediate allies, he cared for them anyway. These were proud moments.

James Wright describes more of the Corpsman focus in Enduring Vietnam. For him, the commitment to care was not just “stabilizing wounds, stopping bleeding…and getting the wounded out of there.” Rather, Corpsmen had a responsibility to care for those who were going to die. Using an example from a similar job position, an Army medic, Wright describes actions from the Battle of Ap Bia, a 1969 battle more commonly known as Hamburger Hill. One medic noted his practice of dosing additional morphine to those who would die, as well as the importance of smiling at them so that they thought they were “going to be okay.” Having the composure and focus to comfort dying men is imperative to the Corpsman Narrative of bringing help and peace in a paradigm of chaos.

Wright brings in a quote that serves as a great summation of the Corpsman mantra: “for myself I just saw my job as trying to keep these boys alive. That was everything for me. When we made contact, someone was always hit early and it was my job to move. I was life and if I moved we would be OK.”

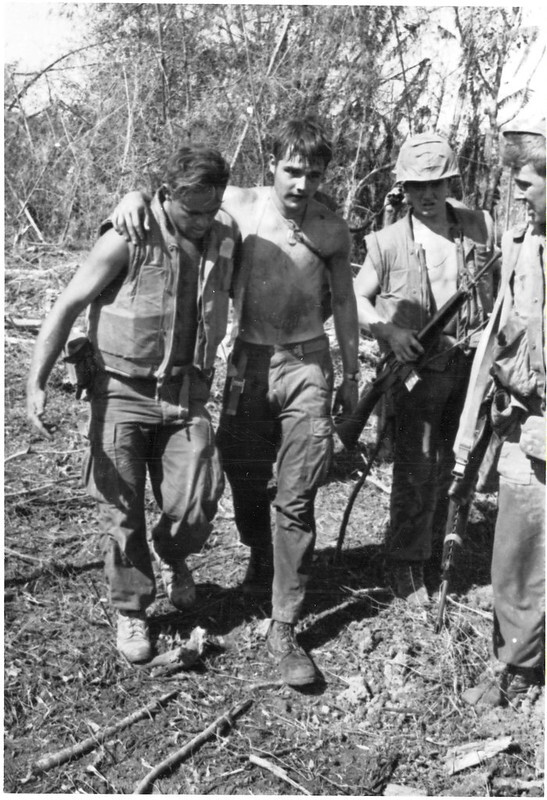

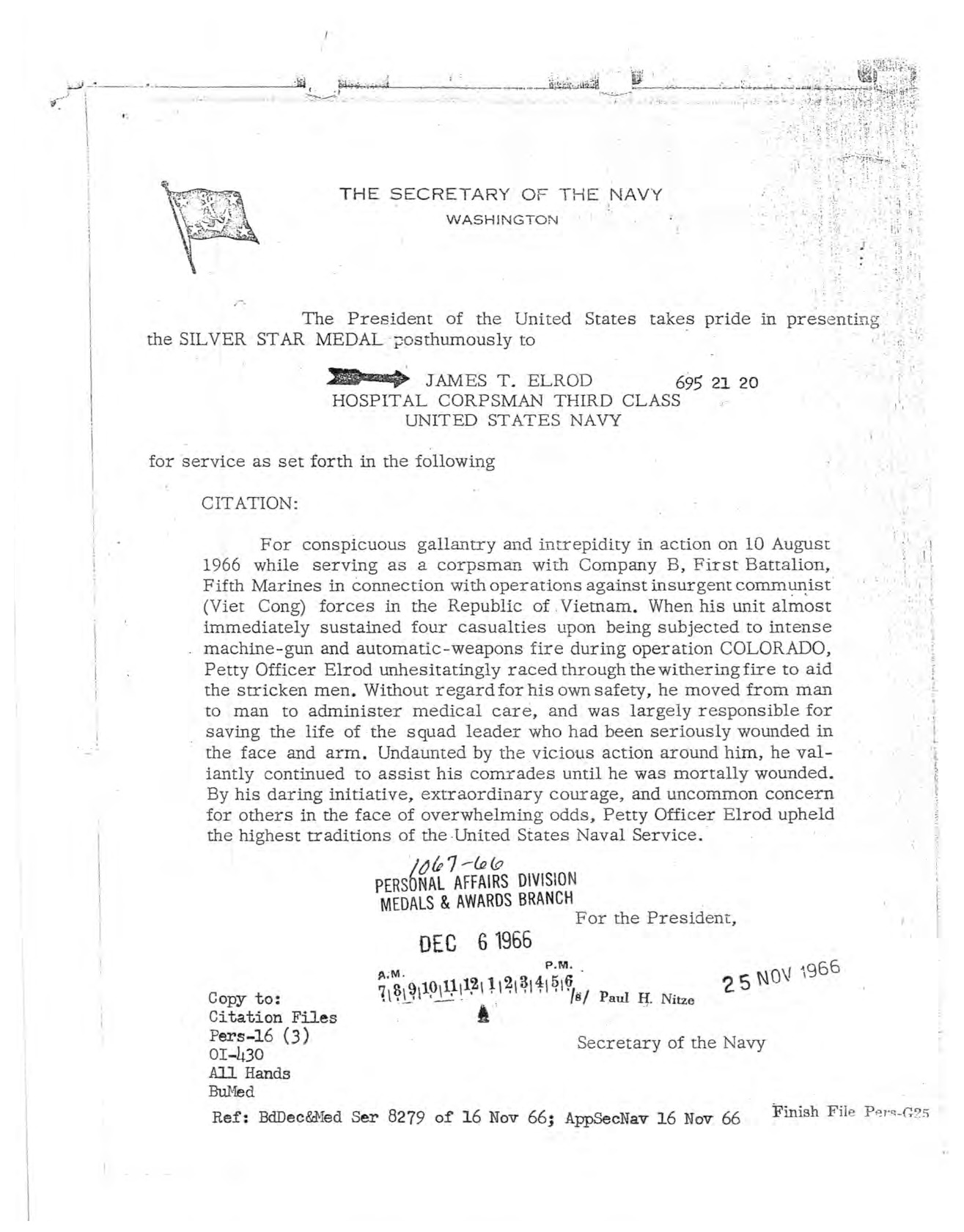

At the right is the posthumous Silver Star Citation for Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class James T. Elrod, one of 645 Corpsmen to perish while fighting in Vietnam. Out of the 10,000 Corpsmen who served, 3,000 suffered wounds. This citation demonstrates the Corpsman narrative's theme of commitment to the job. "Undaunted by the vicious action around him, he valiantly continued to assist his comrades until he was mortally wounded." Elrod's selfless actions saved his squad leader and many men from his company. Elrod did not act on the basis of trying to earn recognition, but rather just out of the commitment to saving those around him. Along with describing moments that they exhibited remarkable bravery, Corpsmen Cassidy and Cahill both narrated instances in which fellow Corpsmen made the ultimate sacrifice. Part of the Corpsman narrative was sacrifice. These men were eager enough to save their Marines that they gave up their own lives to do so. Although death is a negative aspect of these narratives, understanding the willingness to make this sacrifice is an important part of the Corpsman narrative.

Though the difference between focusing on wound description and the saving of men might seem minute, it is grand. Corpsmen, through focusing on their actions to save their Marine counterparts, being willing to give up their lives to do so, and being proud when their treatments worked, demonstrates just how far these men were willing to go to provide relief in a world of chaos.