Keeping the Stove Burning: Labor and Traditional Family Dynamics

“I don’t want my kids to sell tao pho. They’re more capable than that. So that’s why all I want is for my kids to study, because an education will help them have a better job in the future. I’m still young and I’m ready to continue at this job until my children have their own families, or as long as my body can handle this type of work. For now though, I’ll just keep working hard, keep investing in my kids’ success. These days, they are starting to be in a position to help me out financially, but I always refuse to accept their money. I know they need to pay for their education and other expenses; as a mother, nothing makes me happier than seeing my children grow, become independent, and have a good job. I’ve never thought of them having to pay me back.” – Lien, tao pho maker

Work, as the central means by which one maintains their livelihood, is intimately bound with notions of familial obligation. Almost without fail, the oral histories of contemporary managing finances and breadwining for the houshold. In Vietnam, where access to higher education and urban resources is relatively limited, parents managing the burdens of parental responsibility often turn to the market to provide their children with access to opportunities they never enjoyed themselves. This holds particularly true for parents who came of age in the decades before Đổi Mới, anxiety loomed over the labor force due to the expropriation and record-high inflation rates.

Children are also implicated in this dynamic. Research suggests that most Vietnamese children, particularly those of the urban working class, come of age with a distinct financial consciousness. The completion of their educations, enjoyment of leisure activities, and decisions regarding where they might spend adulthood are all influenced by considerations of their nuclear families. Many parents expect families to remain united as they age, so that subsequent generations might care for them later in life. Sociologist Shinya Matsuda’s survey of 389 Vietnamese urbanites found that 100% of respondents believed that caring for ailing parents was the duty of their offspring. Whether conscious or not, the process of childrearing in Vietnam’s developing economy establishes a parental credit for elder care, prompting many children to feel indebted to their parents to a higher degree than in western context. In this way, love can be measured in billable hours.

Confucian Influence

This tendency has largely grown out of the prevalence of Confucian tradition in Vietnam, which still wields considerable influence over the domestic sphere. This influence arrived in southern Vietnam from the north. The southernmost portion of the country, sometimes referred to as Cochinchina, is a relatively new addition to its landholdings when compared to the north. Following the Geneva Agreements’ (1954) division of the nation along the 17th parallel, displaced residents fled to the south, bringing their long-standing cultural traditions with them. This migration of ideas occurred during a period when South Vietnam was undergoing rapid westernization due to its political ties to the United States. In an article published in The Journal of Vietnamese Studies, scholar Nguyen Tuan Cuong describes how the south’s changing political climate helped popularize Confucian thought. “This context of modernization put pressure on the maintenance of traditional cultural institutions,” he notes, “among which were aspects of Confucian culture brought to the South by exiles from the North in 1954.” This culture was defined by an emphasis of loyalty, benevolence, and filial piety.

The impact of Confucianism in the familial context is largely revealed through prescribed gender roles. On the whole, women are expected to present as feminine and follow the “three obediences” found in Female Precepts; these are obeying one’s father in childhood, husband in marriage, and son in widowhood. In the context of the marriage, women assume responsibility for most domestic affairs and chores. Indeed, Matsuda’s study found that approximately 60% of the men surveyed and 70-80% of women believed that women should be responsible for most domestic chores, even while maintain full-time jobs outside the home. Men are likewise expected to embody masculinity, serving as the primary breadwinners for their families and otherwise enjoying the freedom of status of their positions as patriarchs. These expectations are invaluable in their exposure of the cultural bounds within which the Vietnamese labor system operates. Matsuda expertly verbalizes this notion in the previously referenced study, writing: “Through understandings of the Vietnamese family and related gender roles, with their changes in function and structure, the transformation of value orientation serves as an important precondition in understanding the Vietnamese society and its people.”

A Case Study in Subverting Tradition: Hien

A fascinating feature of the Vietnamese workforce is the fact that the apparent dual-burden Confucianism places upon women has not stopped them from securing economic achievement and mobility. One study published in the Comparative Journal of Family Studies in 2010 notes that Vietnamese wives have enjoyed “increased educational attainment and participation in the non-farm sector,” even while accepting responsibility for most domestic chores, particularly during early years of their marriage. As I performed research on this topic, I initially thought that this value system would deeply permeate the market and limit the progress or agency of Vietnamese women, particularly young entrepreneurs. However, I found that this statement is only partially accurate. The influence of the Confucian family model is evident in Vietnam’s economic context, with women remaining keenly aware of how they are perceived by coworkers and customers. I found that Vietnamese women, however, are flipping this Confucian roadmap for behavior on its head.

Rather than remaining stifled by its directives, women have begun using Confucianism as a framework for their business acumen. Expected to outwardly present as Confucian models while still maintaining the skill and nerve that result in business success, Vietnamese women are thus, as Ann Marie Leskowich writes in her illuminating exploration on female entrepreneurs, “central to Vietnamese tradition and yet culturally or morally alien.” In other words, because Confucian femininity precludes women from adopting traditional means of achieving business success (consistent assertiveness, taking customers out on the town, etc.), Vietnamese women have had to develop other means of displaying their virtue and gaining legitimacy. This manifests in what Leskowich later describes as a sort of feminine business ethic borne out of accepted gender norms, particularly that of tinh-cam or a self-sacrificial form of sensitivity to other that allows for the easy continuation of a given interaction. In the context of business, female Vietnamese entrepreneurs demonstrate tinh-cam by deprioritizing their own immediate interests in order to clinch customers and bolster their bottom line. It is a tough business model, but one whose challenges Vietnamese women have failed to succumb to.

This notion is demonstrated by the oral history of a woman named Hien, a former petty trader now running a successful garment factory in Saigon. Her story demonstrates both the impact and subversion of traditional notions of femininity in female Vietnamese entrepreneurship. Her entry into textiles was actually preceded by a venture into construction. Hien, however, decided to leave abandon her previous venture out of concern with high inflation rates couples with a very real consideration that there might be“a more suitable occupation for women like me.”After opening her garment factory in the late 80s, however, Hien enjoyed success in her chosen industry. When questioned about her philosophy in business, she herself claimed that it was defined by notions of sacrifice:

“Vietnamese people, the wife and the husband both, let the wife carry the load…So, I think that the heart of Vietnamese women is that they always sacrifice [hy sinh] for everyone, their life is always sacrifice, including in business.”

This demonstrates tinh-cam at work. Her business ethic also included consistent effort in proving her virtue to others. She works to convey her virtue to others as a demonstration of her morality. For Hien, only the good can succeed in business, as demonstrated by the excerpt below:

“In business, a businessperson is someone who has many strategies to bring profit to himself [sic]. But I believe that a businessperson, I agree that he has many strategies, but these must be consistent with and live in accordance with your conscience, consistent with your heart. Only then will you success. That’s my philosophy in life.”

In short, though traditional values still permeate the business and professional sectors in Vietnam, women have continued to succeed economically. This is largely due to their appropriation of Confucian values in the business world, utilizing their parameters to subvert them. This amounts to the emergence of a business ethic based in feminine morality. Through that ethic, Vietnamese women portray themselves as both virtuous people as well as shrewd entrepreneurs in a contact in which, Leskowich perceptively points out, “it seemed challenging to be either, and nearly impossible to be both.”

The Inherited Business Model

Work plays a crucial role in family dynamics outside the confines of marriage as well. Throughout Vietnam, family units come together to operate business together. Children naturally become heirs to those projects in cases where they are successful, thus extending notions of familial obligation to the economic sector. The economic manifestation of Confucian values occurs from both parents, and children. Indeed, just as children are expected to learn the given industry, parents are expected to open their doors to their children and utilize business projects as a means through which to take care of their offspring and extended family, perhaps most explicitly through their direct employment. This notion is demonstrated in several oral history testimonies, which frame family business as overtly connected with the domestic realm.

My interview with Mary Hong offers one example. As we discussed her immigration to the Unites States in 2013, I asked about what occupation she took up. She began working as a nail technician, she said, because that is what her husband’s mother always did. Thus, when Mary married her husband Stephen, she was accepted into the familial fold and the family business, the Nefertiti Nail Salon, by extension. Mar’s comments are reproduced below:

HONG: Because my family-in-law they everybody do nail. Yeah. My brother-in- law, and my sister-in law, and my aunt, my nephew, my niece - everybody do nail. And Stephen before he just [research? 00:48:26] and he have a [beep? 00:48:29] have a friend introduced for Stephen here.

That's why, my mother-in-law, he thinking is good location, good place. That's why she took over the nail salon. And he, and for a lot of family member working. For Stephen, for my brother-in-law, and his wife, and my nephew, my niece. A family member working, have a place to work.

ARMAS: What is it like working in such close proximity with your family? Is it enjoyable? Do you guys maybe butt heads sometimes? What is it like being surrounded all the time?

HONG: Because we work together and after that we live together, but everybody have personality different. That's why when you working and sometimes you not happy, unhappy, but still family. And when we don't, when we have something different, sometimes something not feel comfortable and we will sit down and we will talk…And until now we fine!

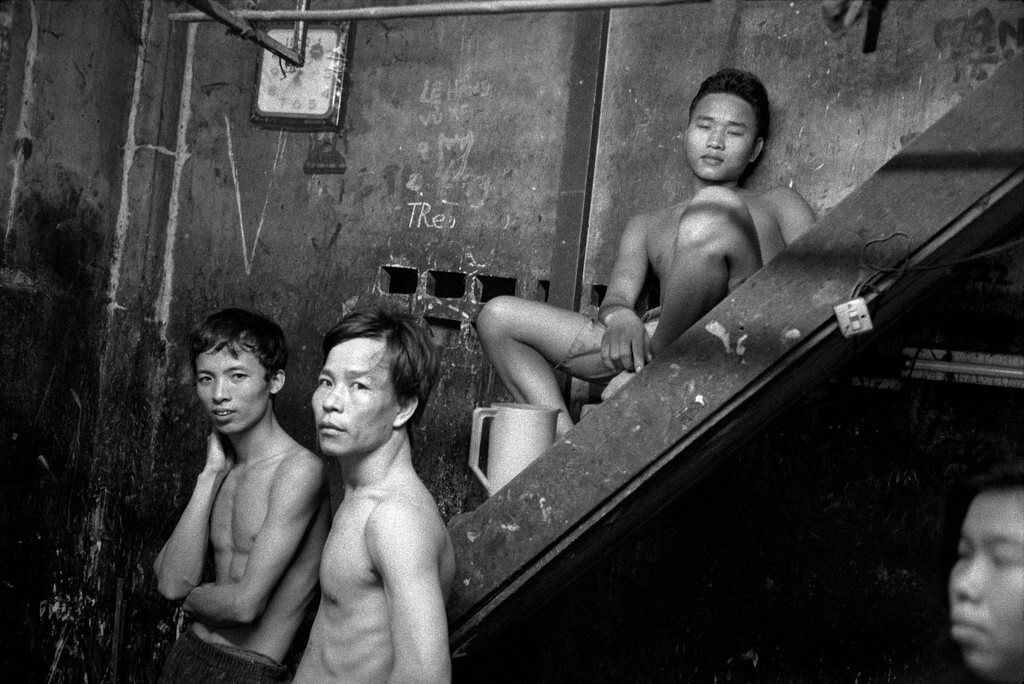

Here, Mary’s comments demonstrate that both the initiation and continuation of the business were designed with family in mind. The last comment she made is particularly interesting, in that it demonstrates a fluidity between domestic and professional conflict in the home. For the Le family, both settings inevitable inform the other. Quyen, a young pho cook working at his family’s noodle stall also describes the ways in which family dynamics bleed into business and vice versa:

“I’ve been seeling pho for five years now. This is a traditional family business: my dad started the restaurant, and now my brothers and I are helping him run it.

Going to school and getting training [to be a mechanic] cost money, and I’d have to ask my parents for it. And as you can see, we don’t make much money selling pho, so I don’t feel comfortable asking them for money. Sometimes at dinner my parents will say, “It’s up to you, if you want, you should go to school,” but I keep thinking about it and it just doesn’t feel right. I don’t have passion to pursue school. And if I do end up going to school, there won’t be enough hands to help out in the shop, so we’ll have to hire someone else. It’s complicated.”

Quyen’s comments reveal how the inherited business model serves to compound familial obligations. Children contributing to the family business are particularly vulnerable to this dynamic. While entrepreneurship provides parents with a more immediate platform through which to perform their Confucian duty, children’s ability to accept their parents help is somewhat limited by their more nuanced familiarity with their family’s finances. In other words, involvement in the family business oftentimes fosters a sort of premature obligation in children, prompting them make value judgements between the achievement of their own goals and the success of the business. Taken together, these narratives demonstrate that the inherited business model largely dissolves emotional distance between kin members and complicates existing cultural notions of familial obligation.