The process of healing: How are Army nurses situated in the conversation about PTSD?

“I came home,” Gayle remembered, “and I said to myself, ‘Now I know what it feels like to be a hundred.’ Because I feel like I'm a hundred. I had no joy, no sadness, no emotion. It was like everything had been drained out. It just wasn't there. No love, no hate, no nothing. No nothing.”

Upon her return from Vietnam, Gayle exhibited classic symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), although that term wasn’t recognized in the gold-standard DSM III until 1980, a full nine years after her return. At the time of her homecoming, Gayle's parents simply concluded that she “didn’t act right sometimes.” When they turned on the news in their family home, Gayle had to leave the room. She couldn’t pay attention while driving because her eyes were trained on the tree line. During hunting season in Upstate New York, she would “go bonkers.” When Gayle saw a South Vietnamese woman at the grocery store, her first thought was “Jesus, I don't have a weapon. I don't have a weapon on me.” Even today, memories of John Lopochonsky still “creep in.”

Gayle’s symptoms of PTSD reflect those of other Army Nurse Corps veterans. “A piece of me got old in Vietnam and a piece of me has been an old lady ever since Vietnam, even though I was only twenty-two when I was there," said a former army nurse, quoted in Norman, who now lives in Pennsylvania.

Lynda Van Devanter, author of the autobiographical Home Before Morning, attempted to forget Vietnam by drinking and sleeping with men, Vuic summarized. Van Devanter considered suicide. It was nine years after she returned to the United States -- while hiding in a public bathroom after hearing sirens blare in a nearby fire station -- that she realized that she needed to seek help.

More concerning was the fact that nurses like Lynda and Gayle wouldn't talk about their experiences when they arrived home. There was no one who truly understood, and bringing up the carnage was impolite. In a paper exploring the lessons learned by Army nurses in Vietnam, researcher Elizabeth Scannell-Desch quotes a nurse who reflected that, "We did our jobs and we went off duty, and we tried not to think about it or talk about it ... I thought, 'Well, I'm the one that's having a hard time and not anybody else, so I just never talked about it.'"

It’s easy to see in hindsight that the wartime trauma of nurses – its frequency, emotional valance, and necessary repression – developed into Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In the early ‘70s, however, the idea that a man – let alone a female nurse in lipstick in heels! -- would suffer so greatly an invisible illness was dubious. Veterans faced social stigma as being categorized as having a “problem” (specifically, a “disease”) if they publicly sought help. Gradually, research advanced, what doctors had assumed was ‘shell shock’ after World War I and ‘combat fatigue’ after World War II became a national scientific conversation about post-traumatic stress, according to Elizabeth Norman. In 1975, two years after the last American soldier left Vietnam, Horowitz and Solomon predicted in their landmark paper that not only would many male Vietnam veterans face stress-response symptoms, but that clinicians would be unable to provide effective treatment. In the years that followed, a flurry of researchers studied these men and came to assign their symptoms as those of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. What was missing from these expert conversations was the experience of female veterans.

It was not until the ‘90s that research explored the relationship between the experience of female veterans and post-traumatic stress. PTSD researcher Jessica Wolfe, in a study conducted in 2000, cites a 1992 poster presented at a conference of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies that found that female Vietnam veterans exposed to war-related stimuli had higher heart rates as compared to a control group. In a 1994 study, Wolfe and others linked symptomatic PTSD in female Veterans with poor health outcomes. In 1995, conversations about PTSD in women eclipsed the confines of veteran experience; researchers found that PTSD is twice as prevalent in women than in men in the general population. Most recently, in 2007, Turner, Turse, and Dohrenwend found that “male veterans in low-exposure circumstances display a level of PTSD prevalence substantially lower than female veterans.”

While studies may have validated the experiences of female Vietnam veterans and certainly provided support for increased public dollars to be put towards PTSD treatment for veterans, women did not need to be told what they knew: that Vietnam fundamentally changed them.

The post-war healing process of Gayle and, likely, a number of her Army Nurse Corps peers is complicated by their occupation as caregivers. While some women abandoned a career in nursing after Vietnam, others like Gayle felt that Vietnam clarified their calling to be a nurse. As a nurse and counselor at a Veterans Affairs hospital, Gayle necessarily relived her Vietnam trauma while counseling male soldiers. Gayle said that male veterans are comfortable speaking to her because “they don’t have to hide anything.”

“I already knew. I know what they did. It wasn’t pretty,” she explained, referencing the violence inherent to war that male veterans committed in Vietnam. Gayle, ever the caregiver, allowed herself to step back into Vietnam by exposing herself to stories of fellow veterans.

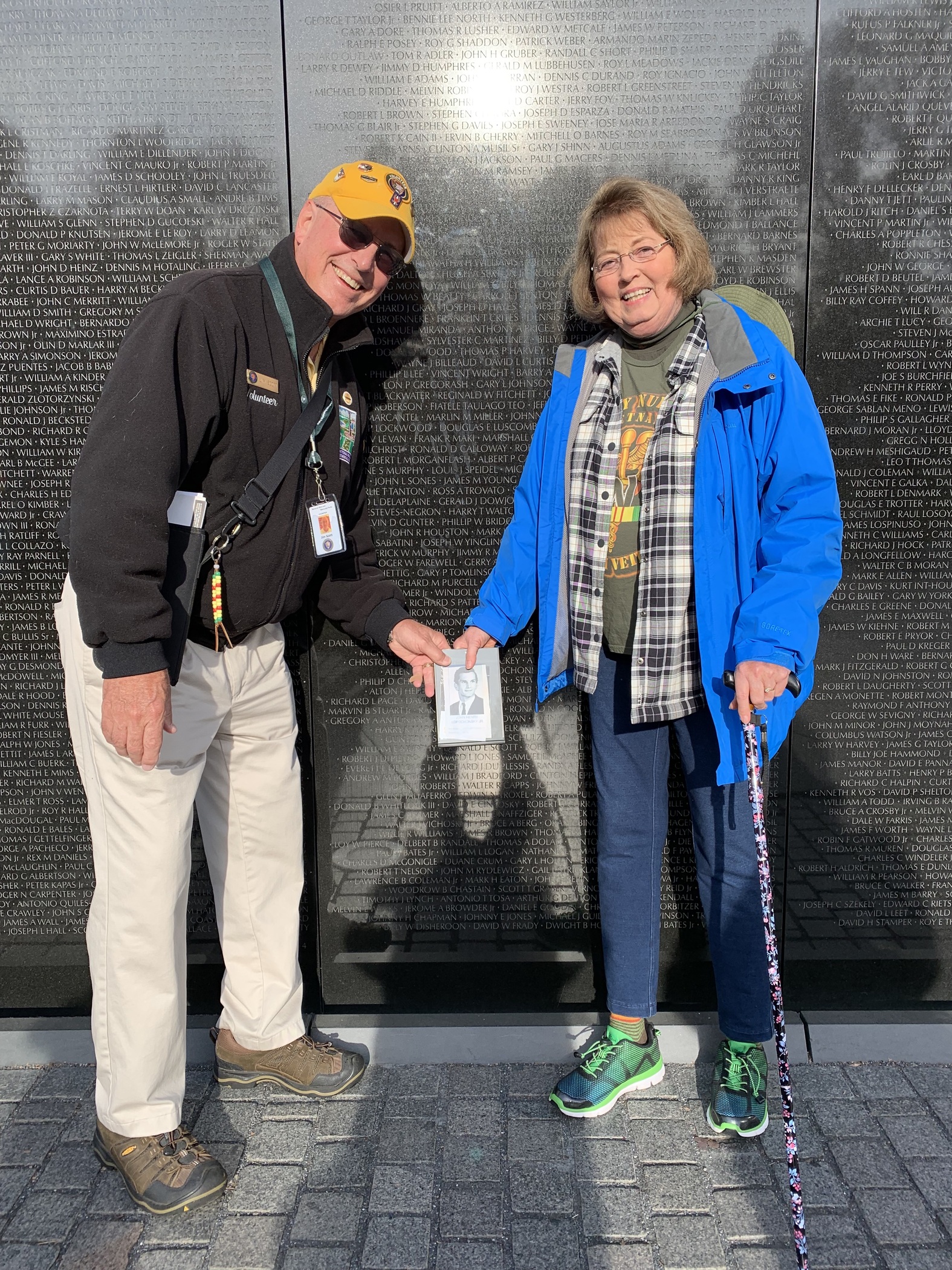

Gayle was quick to share that she suffered from PTSD, and jokes that her husband, Dr. Matt Friedman, chose to work at the forefront of PTSD research after meeting her ("She gave me some credibility!" Matt joked in an oral history with the Dartmouth Vietnam Project). While Gayle's PTSD has faded, she still experiences spikes of trauma. Gayle admitted that she had trouble sleeping during the nights leading up to our interview. “But we’re nearly done,” she said. These days, “[my memory of Vietnam] doesn’t stop me from doing stuff.”

Despite the trauma from Vietnam, when asked if she would choose to serve again, knowing what she knows now, her response was immediate: “Yep. If I could. When 9/11 happened, I had two little kids at home. And I found out about it, and went ‘Jesus – I had to get a uniform back on.’ And I went, ‘Wait a minute: I did my time in Hell and I’m married, I have two little children, I can't do that. I can't do that.’”

A new chapter of her life prevented Gayle from serving again. Her itch to heal, to listen, and to sacrifice is still strong. Despite trauma, a passion to heal has persisted.

"I'm not sure I've ever enjoyed nursing as much as I did that year," said a nurse in Norman's book. "It was the most exciting, the most challenging, the most stressful, and the most important nursing practice I've ever done."

Heather Stur quotes Lynda Alexander, a member of the Army Nurse Corps, in her book Beyond Combat as saying, "This was the real thing. You ever talk about having a feeling of satisfaction, such need? Somebody cared what you did. It was just the most down to the bone thing.”

The work of an Army nurse in Vietnam was a matter of life or death. That’s exactly what made the experience so traumatic and yet so rewarding. Army nurses sacrificed for their country and have paid the price for that service in hushed conversations among friends and in cold sweats following nightmares for years after. Evidenced in their oral histories, Gayle and her fellow Army nurses continue to show us just how brave the role of caregiver can be.

*